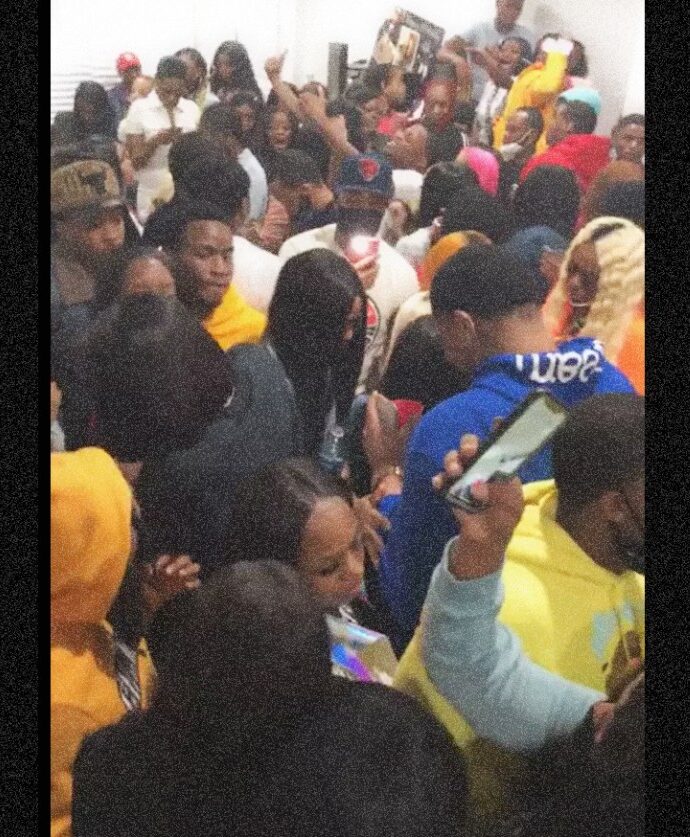

The TMZ headline “1,000 People Attend Chicago House Party During Coronavirus Pandemic” was worrisome to Tiffany Walden, editor-in-chief of The TRiiBE, a digital outlet that aims to reshape the narrative about Black Chicago. She was already following social media comments on a viral Facebook video posted on April 25 showing a jam-packed party in a West Side Chicago residence. Like many Chicagoans stuck at home during Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s meme-worthy lockdown order, Walden had questions.

So did traditional media outlets that followed up on the TMZ release.

The Chicago Tribune was interested in what Illinois Governor Pritzker had to say. An April 26 headline read: “Video of crowded party said to be in Chicago prompts Gov. Pritzker to warn social distance violators: ‘You’re putting everyone around you in danger.’”

An April 27 NBC 5 online story was labeled “WEST SIDE: Homeowner Cited After Massive Party Held at Residence on Chicago’s West Side, Police Say.” The broadcast reported on a “party house crackdown.”

The Chicago Sun-Times April 29 headline read: “Party shut down by cops was held in townhome owned by CFD commander,” referring to the Chicago Fire Department.

“I had this feeling that TMZ was doing this very sensational, stereotypical, and dangerous narrative around Black people in Chicago,” Walden says. “I had to figure out what was going on because I know there aren’t many homes in Chicago where a thousand people can fit in them.”

Walden, who is Black, grew up in a low-income area of the city’s West Side. Even within the Black community, “West Side” is code for a certain kind of Black experience — low-income — when compared with the middle-class Black experience of people living on, say, Chicago’s South Side, according to Walden.

Walden reached out to freelance writer Vee L. Harrison to dig into this disturbing tale of failure to social distance at a time when African Americans nationally were suffering disproportionately from the coronavirus. The TRiiBE would do one thing none of the other outlets would initially do: Talk to someone who was there.

While traditional media outlets pointed fingers at the Black partygoers, Harrison talked to the woman, Tink Purcell, a mother of two, who made the video. She found out that the partygoers were memorializing friends who had died as a result of gun violence in 2018. The "aha” moment of the story was when Purcell and others said they did not perceive the coronavirus to be as dangerous as it is. The story quotes MTV host Dometi Pongo saying news media weren’t connecting with young, Black Chicagoans.

Walden says punitive coverage didn’t take into account that many of these partygoers live in low-income neighborhoods with few resources to make staying at home bearable. They may live in areas with limited internet access or in homes where staying in the house for an indeterminate amount of time may not be safe for everyone. The TRiiBE also connected this experience with underlying issues that may have informed the partygoers’ attitudes. The story quoted Black state representative La Shawn K. Ford, who is from that side of town and evoked police brutality, gun violence, and poor schools as some of the reasons it might be difficult to connect with parts of the Black community.

The TRiiBE’s headline reflected these insights: “A West Side house party exposes the disconnect between young Black Chicago residents, Chicago officials, and the news during the Covid-19 pandemic.”

As part of what might be described as “the new Black press”— outlets that advocate for and culturally represent Black people but are not necessarily Black-owned, are largely digital, nimble, and take an expansive view of who and what constitutes journalism — The TRiiBE was well-positioned to display an empathetic understanding of the community it covers. The racialized economic and health disparities that emerged during the coronavirus pandemic and the outrage that followed the killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Rayshard Brooks underscore fresh opportunities for the cultural nuance and campaigning coverage the Black press has always offered.

Newsrooms, too, cannot escape the racial tension — and exhaustion — of this cultural inflection point. Blacks in salaried positions comprise 7% of newsrooms that answered the 2019 American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE) survey, compared with whites, who occupy 78% of those jobs; Hispanics hold 7% and Asians 5% of salaried newsroom positions. The ASNE survey showed that 80% of newsroom leaders are white, compared with 7.6% who are Black.

Resignations at The New York Times opinion section and The Philadelphia Inquirer and turmoil at The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette stand as emblems of an enduring belief among minorities in the news industry that the “objectivity” standard is merely a tool of racial bias that establishes white norms as the measure of newsworthiness. Staffers at The Washington Post circulated a petition to address the hiring, pay, promotion, and retention of Black employees, and the newspaper has created several new positions that intersect race and other topics as well as a senior leadership position, managing editor for diversity and inclusion. The Los Angeles Times also is facing complaints over the lack of Black staffers.

“News and reporting about Black communities, which is what mainstream news offers, is a lower bar than news and reporting for Black communities,” says journalist and researcher Carla Murphy, who is working on a report about the Black news ecosystem for the Center for Community Media at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY.

Outlets like The TRiiBE; theGrio, a video-centric site devoted to African-American perspectives; ZORA, a publication for women of color hosted on Medium; digital sports and culture site The Undefeated; Coronavirus News for Black Folks, a newsletter focused on the disparate impact of the pandemic on African-Americans; The Root, whose tagline is, “The Blacker the Content the Sweeter the Truth”; Outlier Media in Detroit, which leverages text messaging to drive coverage; The Plug, a news and insights platform covering the Black innovation economy; Blavity, a community for Black creativity and news; and networked journalism, which includes citizen journalists as well as trained professionals in the production of news are some of the sites and initiatives targeting Black audiences that have found their sweet spot in providing news, information, and resources for Black communities as national attention has been focused on the coronavirus and the protests following Floyd’s killing.

Of course, Black people have always found it necessary for their lived experiences to be authentically narrated through vehicles they control. That was the impetus for the 1827 founding of Freedom’s Journal by African Americans John B. Russwurm and Samuel Cornish. Born enslaved, Ida B. Wells found power and purpose as part owner and editor of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight. (She shortened the name to Free Speech.)

For a long time, legacy Black outlets served as a corrective frame for a more authentic, nuanced Black American story. They were the go-to publications for Black representations of joy and beauty, as was the case with Ebony magazine, founded by John H. Johnson in 1945. Jet magazine, which debuted in 1951, helped catalyze the civil rights movement in 1955 when it published photos of mangled 14-year-old lynching victim Emmett Till in his casket before his funeral at Chicago’s Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ.

Currently, there are about 200 Black-owned newspapers in the U.S., according to the National Newspaper Publishers Association. A 2019 Pew Research Center chart detailing paid circulation of several Black newspapers illustrates the loss of influence among legacy outlets. Using data from the Alliance for Audited Media and Verified Audit Circulation, the chart shows The New York Amsterdam News, for example, reached 13,175 subscribers in 2006 compared with 6,786 in 2018. At its height, Jet’s weekly circulation was about 1 million; in 2016, Jet and Ebony and their online counterparts were purchased by Texas-based Clear View Group. In 2014, Jet went online exclusively with no new stories since 2019. Ebony.com is a shadow of its former self, and Clear View did not respond to queries about its plans for the print version of Ebony.

The new Black press is changing the lenses of victimization and dysfunction into lenses of empower- ment and agency

At least 10 Black legacy outlets have joined the newly launched Fund for Black Journalism — Race Crisis in America, organized through the Local Media Foundation. The campaign aims to raise $2 million to create shared video, data, and investigative reporting projects and provide stipends to help local outlets enhance their reporting on race issues. Participating media organizations include New York Amsterdam News, The Atlanta Voice, Houston Defender Network, The Washington Informer, The Dallas Weekly, St. Louis American, Michigan Chronicle, The Afro, Seattle Medium, and The Sacramento Observer.

Nancy Lane, CEO of the Local Media Foundation, says the idea for the fund came from Elinor Tatum, publisher and editor-in-chief of the New York Amsterdam News. When an organizing committee talked about what better, more comprehensive, and shared coverage would look like, Lane says, the idea was, “Let’s empower Black newspapers to tell these stories and, most importantly, propose solutions. Black voices need to be heard.”

There is “still a yearning for a more complete look at the Black experience because we just don’t have that many vehicles,” says Charles Whitaker, dean of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications. “Today, we still see African Americans through the lens of victimization or as perpetrators of crime through the lens of dysfunction.”

Driven by the urge to address the depresencing of Blacks from their own narratives, the new Black press is changing the lenses of victimization and dysfunction into lenses of empowerment and agency. A look at select outlets:

TheGrio

TheGrio, owned by Entertainment Studios, responded to the nationwide pandemic shutdown and subsequent economic losses with a series of videos that addressed how the coronavirus is affecting Black entrepreneurs, called “Staying in Business,” a partnership with Facebook Watch. The series spotlighted everyone from Black travel agents to people driving for Uber and Lyft, “just talking to them and having real conversations about how this whole pandemic was affecting them,” says Todd Johnson, theGrio’s chief content officer. “Over the course of four episodes, we were able to track and hear from everyday Black folks — men, women, young and old — about how this national issue … is literally affecting Black people in different cities, New York, Atlanta, Chicago and other areas.”

Among business owners showcased by theGrio’s Natasha Alford were Vida and Virginia Ali of Ben’s Chili Bowl in Washington, D.C. They discussed the difficulty of accessing emergency funding approved by Congress to keep their restaurant going and their workers working. “If you didn't close for the ’68 riots, we're not going to close for this one,” Vida said.

Alford, vice president of digital content, also featured Ron Busby, president and CEO of U.S. Black Chambers, Inc., who urged people to spend their emergency money at Black businesses: “If 100,000 of those Black people say, ‘You know what, of this $1,200, I’m gonna take $200 and spend it with a Black firm,’ that would be $20 million back into our economy overnight,” he said, snapping his fingers.

ZORA

Vanessa De Luca, editor-in-chief of ZORA, a Medium Corporation site, felt her publication needed to dig deeper than mass media outlets in reporting on safety issues Black people could face when masked up in social environments already hostile to their presence. The essay, “Telling Us to ‘Tip Our Mask’ Is Racist,” resonated with the ZORA audience. Writer Danielle Moodie explained how racial profiling by police affects the Black community and would likely worsen as the government mandated face coverings in public.

Referring to armed white protesters who entered Michigan’s capitol building in April to demand the state reopen, Moodie described the hypocrisy of “heavily armed, angry white mobs” who stormed government buildings, flaunting their privilege to do so without being attacked by law enforcement: “Why? Because in America, armed White people in masks are considered good patriots, while unarmed Black people in masks are perceived as a threat.”

Pieces like this reflect how ZORA’s audience is “looking for those nuances in between,” De Luca says. “We’re looking at a very specific point of view, from a very specific point of view, and an experience that can only be told through our lens as opposed to just telling a story about how to wear a mask or how to make a mask at home.”

The Undefeated

The Undefeated, owned by The Walt Disney Company, spoke into a difficult moment when the video of Arbery being hunted and killed by white neighbors in Georgia horrified all audiences but made African Americans feel particularly vulnerable to what amounts to a modern-day lynching. The outlet highlighted the stakes in its interview with track and field legend Michael Johnson, “Olympian Michael Johnson on Ahmaud Arbery: ‘This is not about running.’”

Johnson admitted he hadn’t heard about Arbery’s killing until the video was released on social media. Though it’s uncustomary for Johnson, the former world-record holder in the 200- and 400-meter events, to speak publicly on social or political issues, he told The Undefeated’s Martenzie Johnson that he felt compelled to bring awareness to the mishandling of the case: “This is about Black people being able to live their lives without fear of consequence that someone is going to make a set of assumptions about them and call the police on them, or in this case, take action into their own hands by making an assumption that they’re a criminal.”

Coronavirus News for Black Folks

Patrice Peck, a former BuzzFeed writer, had been planning to launch a newsletter and grow her own audience when the pandemic hit. She was grounded in facts about health disparities and the Black community and says she relished the opportunity to be her own gatekeeper so she didn’t have to justify why her ideas about Black people are newsworthy or “fit within” a news organization’s scope.

Early on in her work on Coronavirus News for Black Folks, Peck tackled the topic of conspiracy theories to address suggestions within sectors of the Black community about so-called immunity to the coronavirus and how the virus is transmitted. She centered Black subject-matter experts, like Patricia Turner, a folklorist who is also senior dean and vice provost of undergraduate education at UCLA, who parsed the difference between unsubstantiated stories and universal truths about the Black experience in the U.S. healthcare system.

As a key example, she highlighted the Tuskegee syphilis experiment conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972 in which Black male sharecroppers in Alabama were subjected to unethical medical procedures and misinformation as public health officials observed what happens when syphilis goes untreated. The trickery and the pain and suffering caused to these men and their families are what undergird the medical establishment’s polices on informed consent today.

While still in start-up mode and building her audience, Peck has set up a Patreon page offering various levels of membership, which all include access to Weekly Live group creative brainstorming sessions, video and audio exclusives, bimonthly live Q&As, and "Writer's Cut," compelling information that didn't make it into a published piece. Monthly memberships start at $9, $19 and $49 up to levels for $299 or $499.

The Root

It’s not every day that a news outlet can call a major presidential candidate a “lying MF” and get away with it, but when you’re The Root, part of G/O Media, that’s just another day at the office.

Michael Harriot’s nuanced essay about coming of age in the Black community and the trials of upward mobility, published in November of 2019, was a sacred and profane rejoinder to Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg’s resurfaced 2011 comment about children from lower-income, minority neighborhoods. The candidate claimed at the time that these children were not supported by people who value an education. Harriot’s plainspoken language — which got Buttigieg to call him the next day — resounded with The Root’s affluent, educated Black audience, which overindexes in the 25-54 age range and skews female.

Harriot dressed down Buttigieg for offering respectability politics as the answer to education access and equity, saying the candidate had “never attended a school with more than 10 percent Black students.”

“Apparently, it’s not the fact that the unemployment rate for Black college graduates is twice as high as the unemployment rate for white grads. Black college graduates are paid 80 cents for every dollar a white person with the same education earns … Get-along moderates would rather make shit up out of whole cloth than wade into the waters of reality. Pete Buttigieg doesn’t want to change anything. He just wants to be something.”

Danielle Belton’s team at The Root is intentionally counterintuitive, and it is working. Because The Root is part of the G/O Media family of titles that also include The Onion and Jezebel, even non-Black audiences get to listen in on “lodge talk,” private, culturally specific conversations shared among African American community members.

“I’ve always thought people would be more likely to consume an article if they were entertained by it no matter what the subject was,” says Belton, the editor-in-chief. A story “could be horrible, it could be sad, it could make you angry — as long as it’s tied to that emotional chord … written in a creative or interesting way that kind of elevates the conversation.”

Outlier Media

Though Outlier Media doesn’t identify as the Black press per se, Candice Fortman, the outlet’s chief of engagement and operations, acknowledges that serving low-wealth information in a nearly 80% Black community means that race does matter: “For us, serving the city is about serving a population that has been underserved.”

Outlier took that philosophy to heart when it launched a Covid-19 texting campaign to share resources to help residents navigate the pandemic. The team curated resources to help residents in the areas of housing, debt, unemployment, health, and public safety. They shared flyers at local social service agencies, and Fortman posted in “tons of Facebook groups” so community members would know where they could turn to ask questions. In most cases when a Detroit resident texted their zip code and designated an area of query, they received automated answers directing them to next steps. In other cases — more than 200 during a week that elicited more than 700 texting engagements — residents needed a personal touch.

One man with long-term health issues that he understood well needed help figuring out his best options, Fortman recalls: “They need somebody to figure out who they can trust, like, ‘I'm getting information from all these different places. Who should I listen to?’”

Sometimes, the questions are so good, Outlier launches accountability and investigative pieces, including a story — published by published by The Detroit News and aired on “Reveal” — about a dilapidated house that neighbors wanted the Detroit Land Bank Authority, the city’s largest property owner, to tear down. “We are not the assignment editor; our community is our assignment editor,” Fortman says. “We have basically outsourced the assignment editor role to the community [by asking], What do you need to know?”

The Plug

The Plug, founded by Sherrell Dorsey, is a subscription-based digital news and insights platform covering Blacks in the technology and innovation economy. The site renders Black people in tech as real, as they are traditionally depresenced in common conversations about the sector. With a team of 15 contractors, The Plug leverages a newsletter, industry-specific databases and events, such as a Zoom call with Andre M. Perry, the Brookings Institution Fellow who recently published “Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities” to build out an authentic narrative about what Black people in the technology sector are building and innovating — a phenomenon mainstream tech media fails to make clear.

A recent data set of tech company statements and a graphic visualization released in the wake of mass protests over police brutality resounded with The Plug’s audience. The Plug curated links to statements on racial justice, Black Lives Matter, and the May 25 police killing of George Floyd, a Black Minneapolis man. The dataset includes company name, CEO, statement link, time of release, diversity report link and year of release. The document tracks over 200 companies such as Twitch, Spotify, Logitech, Microsoft, Zoom, and Hulu.

“It was a lot of folks who initially wanted to understand, ‘Are you all just paying lip service,’ which of course, many are,” Dorsey says. “Also, who's really stepping up and for the first time centralizing where Black representation happens across these companies that had very bold things to say publicly kind of as part of their PR versus what representation actually looks like within the ranks of their employment.” Dorsey says Black tech workers were “blowing up my DMs,” including direct messages through Signal, an encrypted messaging platform. “For the most part,” she says, “Black tech workers in particular just demanded more accountability.

Tracking tech company statements from the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown, which ignited Black Lives Matter, till now reveals a pattern that helps explain the experience of Black people in the tech sector, Dorsey adds: “What's been true for white moderates or white liberals is there's kind of this propensity to say things and to not actually make a sacrifice to ensure the long-term survival of Black and brown folks.”

Blavity

When Blavity was established in 2014 by Morgan DeBaun, Jonathan Jackson, Jeff Nelson, and Aaron Samuels, the site set out to be a community for millennial Black creatives. Travel Noire and AfroTech, part of the Blavity brand portfolio, cover innovative Black entrepreneurs and thinkers, says Zahara Hill, Blavity’s deputy editor. The outlet also runs opinion pieces from community members covering everything from police brutality and anti-racism to #sayhername, a call to stand up for Black women and girls. The site’s coronavirus coverage has focused on solutions Black business owners and others bring to navigating the pandemic.

Hill cites one story — “This Black-Owned Gun Shop Is Committed To Educating, Consulting And Training Black People On Their Second Amendment Rights” — as representative of how Blavity’s coverage highlights “Black people and Black businesses who are essentially not waiting around for anyone’s permission to do the work.” The story is also representative of what Hill describes as Blavity’s ability to speak directly to Black lived experience, while traditional media seem to still be in a discovery phase of how systemic racism works: “Blavity is uniquely positioned because we don't have to spend as much time on [educating newsrooms and audiences]. We can get right to like the more actionable item.” The approach seems to be working: Blavity reached 38 million page views in May, according to Hill, a 150% jump from April.

Networked Journalism

According to Allissa V. Richardson, assistant professor of journalism and communication at the University of Southern California, Annenberg, traditional outlets often fail to consider residents of marginalized communities as subject-matter experts, one of the reasons the Black community distrusts mainstream media. She also notes how the mainstream media pick up on condescending or outright false statements about the Black community, which further erodes trust. A case in point: Steve Huffman, the Ohio state senator and now-fired emergency room physician who speculated that African Americans, or the “colored population,” in his words, could be suffering disproportionately from the coronavirus because they don’t wash their hands well enough.

Incorporating citizen journalists as well as trained professionals in the production of journalism is an opportunity to create better coverage — and a better working definition of the Black press, argues Richardson, author of “Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones, and the New Protest #Journalism.”

The grip and depth of racial disparities revealed by the coronavirus pandemic and the ongoing problem of the policing of Black bodies are just two reasons for nuanced coverage of the Black experience

Ordinary people using hashtags are really producing journalism about their neighborhoods and often function as first responders in crisis situations, Richardson suggests. She cites the August 2014 uprising that followed the fatal police shooting of Brown, in Ferguson, Missouri as an example of the type of networked journalism that serves the Black community. “There were local people who were tweeting and posting pictures of Mike Brown’s body long before CNN even got there,” Richardson says. The same dynamics were at play in the case of Arbery and Floyd when citizen videos galvanized the attention of mainstream media and overtook the national conversation on policing. (In Arbery’s case, the video was produced by a white man who was later arrested and charged.)

“I would not discredit that work and say they weren’t Black journalists because they were operating very much in the same capacities our ancestors did who reported on lynching and let Ida B. Wells know, ‘You’ve got to get back down here from New York because there’s a fresh lynching you need to document,’” says Richardson, referring to the Black journalist who was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize this year. Richardson recalls Wells’ “The Red Record” (1895), a formal lynching tally of every Black person murdered 1892 to 1894 through extrajudicial or state-sponsored means: “That's exactly what citizen journalists are doing today. By filming, they're keeping their very own red record of all the Black people who have died violently and unnecessarily.”

Networked journalism — user-generated, hyperlinked, crowdsourced — is even more imperative today, says Richardson, given her view that everything from the 19th-century movement to abolish slavery to lynchings to today’s Black Lives Matter protests are the necessary excavation that must occur to keep Black audiences and their experiences from being erased from the dominant news narrative. Where the general public may be occupied with government and other forms of surveillance, the methods employed by contemporary Black protesters function as a form of “sousveillance,” the recording of an activity by participants in that activity as a way to promote accountability from the bottom up. Footage of Floyd and Arbery and the McKinney, Texas girl at a 2015 pool party who was slammed to the ground by a police officer was crucial to getting media and law enforcement attention to these injustices.

The grip and depth of racial disparities revealed by the coronavirus pandemic and the ongoing problem of the policing of Black bodies, through law enforcement and otherwise, are just two reasons for nuanced coverage of the Black experience. Documenting the existence of Black joy is another, because these audiences need and crave both recognition and reckoning.

Richardson aptly recalls James Baldwin’s commentary on Black people’s need for witnesses, which he summed up in a 1984 New York Times interview: “I have never seen myself as a spokesman. I am a witness. In the church in which I was raised you were supposed to bear witness to the truth. Now, later on, you wonder what in the world the truth is, but you do know what a lie is.”