Between September 2001 and November 2006, I was editor of two Knight Ridder papers, first the Lexington Herald-Leader and then The Philadelphia Inquirer. It was a period of intense turmoil. Today Knight Ridder no longer exists. My job as editor vanished when the Inky was sold to a local private equity group, which subsequently filed for bankruptcy.

Back then, the changes were coming so fast that we were all struggling to keep our heads above water—and often failing. Had I known then what I know now, here's what I would have done differently—and how I would use that hindsight even now:

Protesters gather outside The Philadelphia Inquirer after the paper printed one of the controversial Muhammed cartoons in 2006. Amanda Bennett, above, then editor, remains proud of the decision to publish what many papers didn’t. Photo by Rusty Kennedy/The Associated Press.

I WOULD TRUST THE NEWS AND THE NEWSPAPER: With circulation and advertising both dropping, we had a tendency to go apocalyptic. I remember long impassioned discussions about the "future of news," about how young people didn't care anymore, about how newspapers were becoming irrelevant. The panic froze us and perhaps made us less effective at figuring out what our problems were.

Now it's much clearer that people—including young people—want news and that even physical newspapers have long lives ahead. We still have the challenge of redefining what news is, figuring out how people want to get it, and, crucially, how to pay for it.

TODAY: I can see us focusing on what that news should be and how we should deliver it.

I WOULD STOP LOOKING FOR A MAGIC BULLET: Back then, in our panic, we kept looking for big solutions to fix our problems: Zoned editions. Community news. Citizen journalists. The Web. Each was The One Solution or nothing. We beat up our newsrooms, exhausted everyone, and pinned our hopes for transformation on a succession of big bets. Our expectations were both too low and too high. We misread how radical the shift in technology would be and how broad our response would have to be. At the same time we missed how myriad would be the opportunities this shift would create.

TODAY: I would keep trying as many things as possible, including fiddling with different ways of asking people to pay for the news.

I WOULD NEVER ATTEND ANOTHER FOCUS GROUP: Ever. How many prototypes did we gin up? How many boards with different kinds of stories did we pass around? How many times did we hear readers say "Yes! I want THAT!" only to have that section or feature or zoned edition fall flat? How many evenings did we all spend behind the one-way glass window listening to our readers tell us we were too conservative, too liberal, not local enough, too local? Things were changing so fast that readers themselves didn't even know what they wanted. And they certainly didn't know what was coming down the road at them.

I used to say that no one, if asked, would have said that they needed a teeny vacuum cleaner they could hold in their hands. Yet we all now own DustBusters. Similarly, none of our readers would have said: "I want to share the news the second I hear it with anyone I want." Or: "I want to know what my friends are reading as soon as they read it." Yet millions would soon be doing that on Facebook and Twitter.

TODAY: I still wouldn't hold or attend a focus group again. Ever.

I WOULD HAVE STOPPED ENGAGING IN STUPID ARGUMENTS: How much time did we waste arguing about what is the proper profit margin for a newspaper company? How much time did we waste trying to decide whether public ownership was to blame? Profit margin and shareholder pressure may have been stresses on the industry but they were nothing compared to the technological and social upheavals we should have been focused on. I watched and worked for companies that milked every cent of profit from their papers as well as for those that husbanded every newsroom resource for as long as possible. All met with very similar fates. We argued in-house about profit margins and private vs. public ownership at a time when we should have been looking outward.

TODAY: I wonder who wouldn't cheer for an extra point of profit margin.

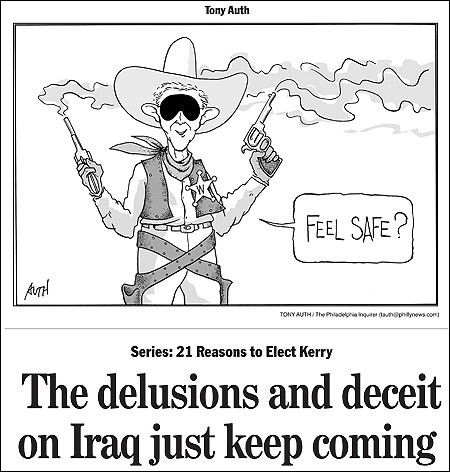

The Philadelphia Inquirer spent months documenting the corruption of a powerful state senator and ran a series of 21 editorials endorsing U.S. Senator John Kerry for president in 2004.

I WOULD HAVE BEEN BRAVER: As I look back on my career as editor, I feel proudest of the times I was bravest: The day I helped the Lexington editorial board craft an editorial saying that there wasn't enough evidence of weapons of mass destruction to warrant an invasion of Iraq. The month in Philadelphia when we ran 21 days of editorials on why John Kerry and not George W. Bush should be elected president. The weekend we ran the controversial Muhammed cartoon. The months and months of tackling a powerful—and corrupt—state senator (who is now in prison).

We editors are brave at standing up to power or danger or opprobrium—as long as it is coming from the outside. We are surprisingly weak at facing down the stares from within our own newsroom when we hear, "That's not what we do," "That's not my beat," or "We've never done that." How many more times should I have said "Yes it is," "It's your beat now," "It's time to try." I should have been braver at recognizing the difference between a reverence for the past and a reluctance to face the future.

TODAY: The future still lies ahead. Why not try?

Amanda Bennett is executive editor for projects and investigations at Bloomberg News. After a 23-year career at The Wall Street Journal, she was a managing editor at The Oregonian and editor of the Lexington Herald-Leader and The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Back then, the changes were coming so fast that we were all struggling to keep our heads above water—and often failing. Had I known then what I know now, here's what I would have done differently—and how I would use that hindsight even now:

Protesters gather outside The Philadelphia Inquirer after the paper printed one of the controversial Muhammed cartoons in 2006. Amanda Bennett, above, then editor, remains proud of the decision to publish what many papers didn’t. Photo by Rusty Kennedy/The Associated Press.

I WOULD TRUST THE NEWS AND THE NEWSPAPER: With circulation and advertising both dropping, we had a tendency to go apocalyptic. I remember long impassioned discussions about the "future of news," about how young people didn't care anymore, about how newspapers were becoming irrelevant. The panic froze us and perhaps made us less effective at figuring out what our problems were.

Now it's much clearer that people—including young people—want news and that even physical newspapers have long lives ahead. We still have the challenge of redefining what news is, figuring out how people want to get it, and, crucially, how to pay for it.

TODAY: I can see us focusing on what that news should be and how we should deliver it.

I WOULD STOP LOOKING FOR A MAGIC BULLET: Back then, in our panic, we kept looking for big solutions to fix our problems: Zoned editions. Community news. Citizen journalists. The Web. Each was The One Solution or nothing. We beat up our newsrooms, exhausted everyone, and pinned our hopes for transformation on a succession of big bets. Our expectations were both too low and too high. We misread how radical the shift in technology would be and how broad our response would have to be. At the same time we missed how myriad would be the opportunities this shift would create.

TODAY: I would keep trying as many things as possible, including fiddling with different ways of asking people to pay for the news.

I WOULD NEVER ATTEND ANOTHER FOCUS GROUP: Ever. How many prototypes did we gin up? How many boards with different kinds of stories did we pass around? How many times did we hear readers say "Yes! I want THAT!" only to have that section or feature or zoned edition fall flat? How many evenings did we all spend behind the one-way glass window listening to our readers tell us we were too conservative, too liberal, not local enough, too local? Things were changing so fast that readers themselves didn't even know what they wanted. And they certainly didn't know what was coming down the road at them.

I used to say that no one, if asked, would have said that they needed a teeny vacuum cleaner they could hold in their hands. Yet we all now own DustBusters. Similarly, none of our readers would have said: "I want to share the news the second I hear it with anyone I want." Or: "I want to know what my friends are reading as soon as they read it." Yet millions would soon be doing that on Facebook and Twitter.

TODAY: I still wouldn't hold or attend a focus group again. Ever.

I WOULD HAVE STOPPED ENGAGING IN STUPID ARGUMENTS: How much time did we waste arguing about what is the proper profit margin for a newspaper company? How much time did we waste trying to decide whether public ownership was to blame? Profit margin and shareholder pressure may have been stresses on the industry but they were nothing compared to the technological and social upheavals we should have been focused on. I watched and worked for companies that milked every cent of profit from their papers as well as for those that husbanded every newsroom resource for as long as possible. All met with very similar fates. We argued in-house about profit margins and private vs. public ownership at a time when we should have been looking outward.

TODAY: I wonder who wouldn't cheer for an extra point of profit margin.

The Philadelphia Inquirer spent months documenting the corruption of a powerful state senator and ran a series of 21 editorials endorsing U.S. Senator John Kerry for president in 2004.

I WOULD HAVE BEEN BRAVER: As I look back on my career as editor, I feel proudest of the times I was bravest: The day I helped the Lexington editorial board craft an editorial saying that there wasn't enough evidence of weapons of mass destruction to warrant an invasion of Iraq. The month in Philadelphia when we ran 21 days of editorials on why John Kerry and not George W. Bush should be elected president. The weekend we ran the controversial Muhammed cartoon. The months and months of tackling a powerful—and corrupt—state senator (who is now in prison).

We editors are brave at standing up to power or danger or opprobrium—as long as it is coming from the outside. We are surprisingly weak at facing down the stares from within our own newsroom when we hear, "That's not what we do," "That's not my beat," or "We've never done that." How many more times should I have said "Yes it is," "It's your beat now," "It's time to try." I should have been braver at recognizing the difference between a reverence for the past and a reluctance to face the future.

TODAY: The future still lies ahead. Why not try?

Amanda Bennett is executive editor for projects and investigations at Bloomberg News. After a 23-year career at The Wall Street Journal, she was a managing editor at The Oregonian and editor of the Lexington Herald-Leader and The Philadelphia Inquirer.