How are great journalists made? Often, it’s pieces of great journalism that help form them, influencing their lives or careers in an indelible way. To celebrate the Nieman Foundation for Journalism’s 80th anniversary in 2018, we asked Nieman Fellows to share works of journalism that in some way left a significant mark on them, their work or their beat, their country, or their culture. The result is what Nieman curator Ann Marie Lipinski calls “an accidental curriculum that has shaped generations of journalists.”

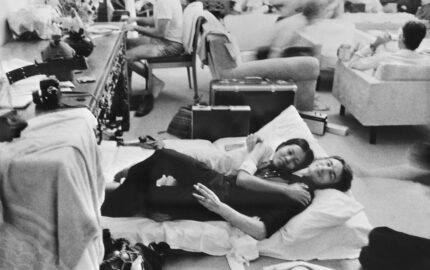

My ninth-grade civics and American history teacher Miss Keister gave me “Winners and Losers” by Gloria Emerson, among the many articles and books she constantly offered me. She fed my interest in history as well as current international affairs, and—apart from my parents—was the single biggest influence shaping my college and career trajectory. “Winners and Losers” was perhaps the book that definitively tilted me toward journalism and international affairs, and specifically societies in conflict. At that time, in high school, I realized that I’d just missed one of the seminal experiences of our country—the Vietnam War—and Gloria’s book helped me “see” it firsthand. She captured in her photos and prose the searing experience of war for those living in that place, both the Vietnamese and the soldiers we sent to fight on behalf of South Vietnam and the anti-communist cause. I spent the first years of my journalism career in Central America covering the anti-communist wars there. Being a woman out in the middle of a war zone did not strike me as a strange idea since I had seen Gloria’s work. In most talks I give the question inevitably surfaces, why do you do what you do? I guess I should just say “Gloria Emerson.”

Winners & Losers: Battles, Retreats, Gains, Losses, and Ruins from the Vietnam War

By Gloria Emerson

Random House, 1976

Excerpt

Somewhere in 1971, in a village called Duc Duc, there was a captured nurse handcuffed to a girl of sixteen. It was the nurse I thought of for too long: even now I can remember something about her face and the color of the jacket she wore—it was not black but a greenish shade. There were handcuffs pulling the nurse and the girl together: they were made by Smith and Wesson. Her husband had been a soldier with the National Liberation Front, she had moved with him and his unit, the nurse said. There had been hardships, she had lacked medical supplies. Coconut milk had once been used in transfusions because there was no blood, the nurse said. Her voice was matter-of-fact. She did not expect pity. The nurse acted as if now she was afraid of nothing. When the Saigon government troops stared at her, she turned her back on them, so the girl handcuffed to her had to shift too. The soldiers did not like what the nurse called them, but they did nothing, standing there in a little schoolboy frieze, arms on each other’s shoulders.

So often I remember the nurse, so much later in places that had nothing to do with Duc Duc, that some Americans in the antiwar movement became impatient. Once I even mentioned her in a restaurant on Mott Street, wondering if she had endured. I was advised not to be foolish, to stop being morbid, I must realize that others had taken her place, the friends said, as if that was the point, as if it was the space she left that haunted me.

Reprinted from Winners & Losers by Gloria Emerson © Copyright 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1985 by Gloria Emerson. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.