The idea for New Canadian Media came to me at the 2009 Nieman Narrative Conference. During a workshop session I met an editor named Andrew Lam who, like me, is an immigrant—he’s from Vietnam, I’m from India—and almost everything he does relates to his diaspora experience. Andrew told me about his job at New America Media, which describes itself as the “largest national collaboration and advocate of 3,000 ethnic news organizations.” Although I didn’t realize this at the time, the idea of pursuing “immigrant journalism” in Canada had taken hold.

I moved to Canada in 2002 and had established a professional foothold in my new country as a commentator on immigration and foreign policy matters for mainstream media organizations. For example, when a commission in Quebec started looking into the idea of “reasonable accommodation” of immigrants in 2008, the Ottawa Citizen invited me to comment on it.

During the seven-hour drive back from the Nieman conference to Ottawa, it dawned on me that editors sought me out precisely because my voice was different—influenced by my travels and sojourn in four countries before Canada: the US, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and India. Still, the idea of “immigrant journalism” incubated for another two years before I mustered the courage to actually do something about it. In May of 2011, I gathered three friends— a lawyer, a sociologist who is also an ethnic publisher, and a Canadian-born marketing professional—around my dining table to put soil around that seed of an idea. I’ve never looked back.

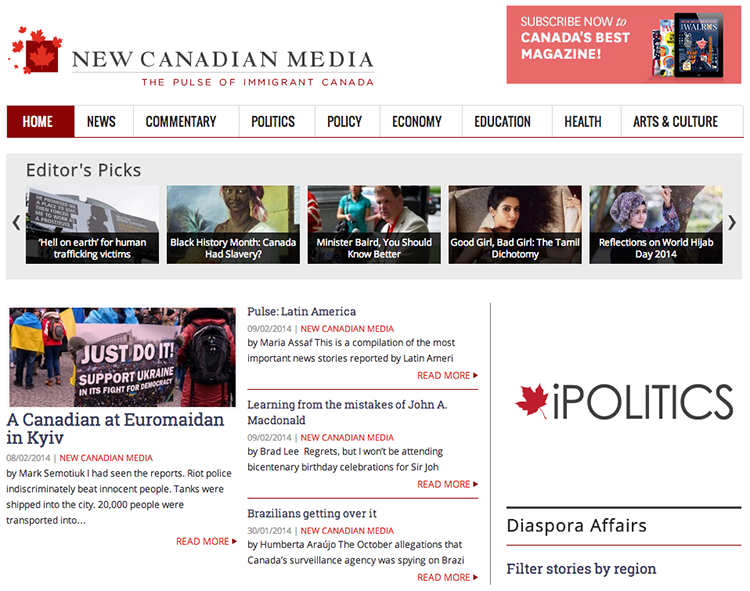

New Canadian Media furrows a growing niche: An immigrant perspective on current affairs in Canada, highlighting topics of particular relevance to newcomers. We use the term “immigrant” to include all Canadians whose views are influenced by memories or an intimate knowledge of another part of the world, from the newly arrived to the grandchildren of immigrants. The former is a rapidly growing market, as Canada welcomes new immigrants at one of the highest per-capita rates in the world. The 2011 Census revealed that one in five Canadians today is foreign-born, comprising 200 different nationalities. In recent years, immigrants from China, India, the Philippines and Pakistan have been the largest groups to gain permanent residency.

Our focus today is not to “break” stories, but rather to offer the “pulse of immigrant Canada” through original news articles, opinion pieces, and headlines aggregated from English-language ethnic media. Done right, these stories can spread. Our most popular piece was headlined “Why I Resigned as Editor,” by a Filipino-Canadian journalist who had just quit an ethnic magazine targeted at his own community. The piece found wide resonance not only among immigrants from the Philippines, but also among mainstream journalists who were intrigued by the editor's commentary on the state of ethnic media.

As a start-up, we are under no pressure to update our site every day, but we keep the buzz going by having an active presence on Facebook and Twitter. In addition to advertising and marketing linkages with other ethnic publications, we are looking at launching an AP-style news agency that will offer mainstream media exclusive content from an immigrant perspective.

I know that online media are a dime-a-dozen, and their failure rate is high. Access to capital remains our largest hurdle, and I’ve learned the hard way that journalism on the cheap can be, at its best, hackery. We are also dealing with the fragmented nature of the ethnic media, where many outlets do not publish in English. In my bleaker moments, when the odds seem overwhelming, I draw on my varied experience in some of the most treacherous countries in the world for honest journalists. I also remember the reassuring words of Bill Kovach, my Nieman curator in 1995: "Keep the faith." It keeps me going: I realize journalism in the 21st century requires us to be not just good interrogators, but also savvy entrepreneurs.