At the time I was a student volunteering with the media relations department. When the news was announced around 11 o’clock, even the most emergency-hardened, leathery-faced humanitarian workers were momentarily speechless as journalists bombarded staff members with a barrage of questions. Even the receptionist made the 1 o’clock news, since she’d been unable to hide behind a desk. Amid all the chaos, an operations manager elbowed his way to our office. He had to duck to avoid cameras. When he finally made it, he told us with a straight face: “Don’t tell the press anything before we’ve discussed whether we’ll accept the Nobel or not.” I remember the media relations officer standing next to me looking like she’d just swallowed an umbrella.

MSF is one of the most media-savvy humanitarian nongovernmental organizations (NGO’s). Despite this supposedly “symbiotic” relationship between aid agencies and the media, a sense of incomprehension inhabits both sides. Humanitarians rely on journalists to raise awareness of the causes in which they are involved. They also depend on our coverage to attract donor funding. Journalists often rely on aid workers to gain access to tell the story of a disaster or crisis and to decrypt what is going on, although they rarely admit to this aspect of their relationship. Both are wary of the other’s agenda, for several reasons.

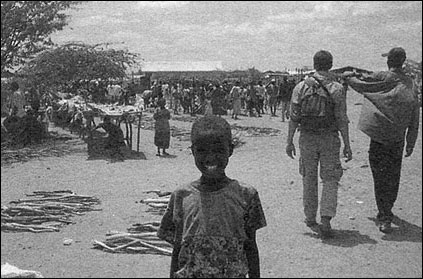

A community leader takes Hilaire Avril (second from right) around the market in a Sudanese refugee camp. A young girl who lives in the camp smiles into the camera. June 2004.

Aid workers often complain that journalists have no understanding of the intricacies of the humanitarian issues they cover. They also resent the “insufficient coverage of their activities.” Most journalists who cover humanitarian crises are generalists; a few are war correspondents. Some are unprepared to grasp the technicalities and exigencies of an aid operation, and most do not appreciate the subtleties of the social, cultural and political implications of humanitarian intervention, although this is where the underlying story is in most aid operations. The Sphere Project, which outlines standards for aid operations, insists that an aid worker have knowledge of the disaster-affected population’s culture and customs. The standard should also apply to journalists.

On the other hand, journalists who deal with NGO’s often experience an apparent contradiction. While those who work at NGO headquarters are typically eager to get press coverage for their operations, their field staffs are often reluctant to talk with journalists once they arrive on site. While preparing for a recent trip to Kakuma camp, the biggest settlement in Kenya for Sudanese refugees fleeing the 20-year-long civil war in South Sudan, I asked a major international NGO’s public information department in New York for field contacts. They were more than happy to provide what I needed, making it possible to bypass the camp’s administration and talk directly with refugees about their hopes and plans in light of the current peace talks. However, the field staff’s approach was very different. The manager told me that the camp staff was not “qualified to speak to the media,” but that she would be more than happy to brief me when I returned to the capital.

The truth is that Kakuma camp— which shelters some 90,000 refugees of nine different nationalities—is under-funded and rundown. It’s a sad, destitute and violent place. Despite the tremendous work several aid agencies perform in this god-forsaken part of the Kenyan arid lands, tribal feuds, raids from the “hosting” Turkana community, disease and sexual violence have plagued the camp since it was set up 12 years ago. Those who are here as humanitarian workers did not trust that I would cover the “whole” story of the camp and explain the tremendous difference this aid effort makes in the refugees’ lives, despite all its shortcomings and lack of resources.

What can journalists expect of aid workers as sources? Most aid workers I know find a source of energy in their healthy indignation at the world surrounding them. This is often combined with a strong antiestablishment stance. On the evening after MSF won the Nobel Prize—and accepted it, since the option of turning it down for the sake of “political neutrality” never stood a chance against the mountain of prime-time exposure—I asked an old-timer who’d worked for years in Afghanistan how he reacted to this worldwide recognition of 30 years of hard work. His answer was sobering: “When I’m back in Paris, strangers in cafés tell me how much they admire us for what we’re doing. But when it comes to renting a flat, people turn me down because I’ve got no credit history.”

Humanitarian workers have a growing skepticism towards journalists, especially those who “parachute” in to do one story and then leave. These aid workers often perceive journalists as being obsessed with finding “good angles” rather than reporting in-depth stories. This is because a few journalists who specialize in covering crises can be ruthless in focusing only on the shortcomings of some aid operations.

But I’ve found that most aid workers will open up if you take time to display empathy and at least minimal awareness of what their tasks entail. Aid workers should also educate journalists about the boundaries they are obliged not to cross. For example, if an NGO is portrayed in media coverage as taking sides in a conflict, such coverage might put the field personnel in danger.

Recently I heard the manager of a feeding operation in Burundi confess in a hushed tone that her organization had been giving food to rebel forces in an attempt to keep them from looting local civilians’ meager resources. To make such a decision must have been very difficult, but this manager told me the approach seemed to be working. However, what journalist covering this story would resist the obvious angle that “aid agencies are feeding the conflict”? Which editor would turn down this angle on the story?

This is why it’s important for relief workers to be willing to explain the dilemmas they face every day. Their job, as I have come to understand it, is often to make the “least worst decision.” But that has to be explained to journalists and, in turn, journalists need to find ways to convey this subtle but critical dimension of the story to readers, listeners and viewers. Humanitarian work is a complex endeavor, and often a political minefield, but its nuances and challenges should be openly exposed.

In 1994 in Goma, in what was still Mobutu Sese Seko’s Zaire, aid agencies confronted a similar dilemma. Hutu refugees were crammed into gigantic camps. “Genocidaires”—the Hutu extremists who had just massacred hundreds of thousands of civilians in the most savage way—were among the civilian refugees. They were actively recruiting and arming young boys in the camp. Should aid agencies have walked away to avoid supporting the mass murderers who were barely hiding among the vulnerable civilians, as some did? Or should they have stayed and fed these killers alongside the innocents?

If those in the West had had a clearer understanding of these circumstances— one that they might have received from well-reported news coverage—it might have triggered an armed intervention that could have separated murderers from civilians. Instead, “genocidaire” militias were never disarmed and still violently destabilize the entire African Great Lakes region.

Broader, deeper and more consistent coverage might also help deflate the “emergency of the season” effect that drains all attention and aid funding to the most widely reported crisis, as has been the case during the past year with Iraq. While the mainstream media extensively cover the plight of the Iraqi people, the fighting in nearby Somalia that still sends refugees fleeing across the Kenyan border—along with several other humanitarian crises—has been off editors’ radar screens since the disastrous end of Operation Restore Hope 10 years ago.

For those of us listening to those who work for humanitarian NGO’s, and to the ones who try to help, unfortunately what we hear is the never-ending possibility of stories.

Hilaire Avril writes for IRIN, the U.N.’s humanitarian reporting service. He volunteered for a few months with Médecins Sans Frontières’ media relations department in Paris in 1999.