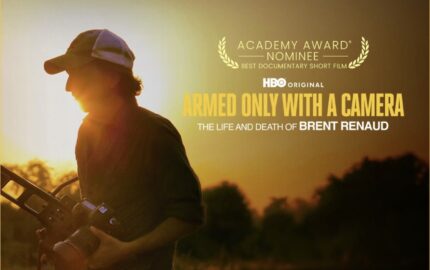

Jason Rezaian, NF ’17, is the director of Press Freedom Initiatives at The Washington Post. He served as the paper’s Tehran bureau chief from 2012 to 2016, during which time he spent 544 days in an Iranian prison — 49 of them in solitary confinement — following his 2014 arrest on false charges of espionage. In addition to writing a newsletter and articles on press freedom and individual journalists under threat, Rezaian leads the Post's Press Freedom Partnership, a coalition of nonprofit organizations dedicated to promoting independent media worldwide.

He speaks about his new role and the need to cover press freedom as a standalone beat.

These comments have been edited for length and clarity.

This work has [been] a core part of my activities at The Washington Post for years, writing about cases of journalists in trouble around the world. When I was arrested over a decade ago, it really wasn't easy for newsrooms to make a decision about how to advocate for a journalist in trouble, even if it was one of their own. That landscape has changed dramatically, and I'm proud to say that I've been part of that shift. Those efforts laid the foundation for a more focused operation, and last year, I was asked to lead it by building on our existing initiatives.

Since 2018, after the brutal murder [by agents of the Saudi government] of my colleague Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul, The Washington Post has stepped up its work in defense of press freedom. The Post’s publisher at the time, Fred Ryan, believed it was vital for our paper to take a clear stand for values that sit at the heart of American democracy. We formalized a range of efforts: creating a newsletter, launching partnerships with leading press freedom organizations, donating ad space for their campaigns, and collaborating on events like World Press Freedom Day. [I write about] cases like Evan Gershkovich [Wall Street Journal reporter previously jailed in Russia] or Cecilia Fala, an Italian journalist who was held for several weeks in Iran, in the same prison that my wife and I were held, to shine a spotlight on them very quickly, to try and increase the likelihood of a quicker release for those people.

In the past, if you had a member of Congress and senators and [press freedom organizations] like the Committee to Protect Journalists or Reporters Without Borders put out a strongly worded statement of condemnation for the arrest of a journalist, that was often enough to free someone. In the past, the public perception of locking up journalists was so negative that no government wanted to be labeled as a jailer of journalists. Now it's almost a goal, right? There is an audacity to the arrest of journalists, accusations of espionage, or other trumped-up charges against people that shows that not only are some governments not worried about the reputational damage that this does, they're actually doing it because they think it's an easy way to quiet dissent.

Today, some governments see jailing journalists as a badge of honor or a tool for silencing critics. ... That’s why it’s so important to tell the human stories behind these detentions.

And I hope readers understand that it’s not all doom and gloom. My work isn’t about despair. It’s about taking ideas and experiences that may feel foreign and making them accessible, touchable, knowable. Because press freedom — like all freedoms — is at a potential breaking point. We don’t have the luxury of waiting and seeing what happens, and it’s time to no longer just be strong. We have to act.

That’s one of the central purposes of the newsletter I write. The other is to underscore why press freedom matters. Ultimately, if we lose press freedoms here and in other countries, these are the kind of resources and rights that are easy to lose but hard to get back. We’re trying to show people these issues are worth fighting for.

As told to Megan Cattel