At the end of December 2020, freelance journalists Matteo Garavoglia and Youssef Hassan Holgado spent a month-and-a-half traveling across Tunisia to report on the 10th anniversary of the Jasmine Revolution, when large-scale protests led to the ousting of longtime president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. What happened in Tunisia ignited similar uprisings all over the Middle East, which came to be known as the Arab Spring. A decade later, Garavoglia and Holgado found a country still struggling with the same issues that prompted the uprising: poverty, widespread unemployment, and social inequality. Resentment toward the political establishment is still prevalent among Tunisians, particularly among younger generations.

Garavoglia and Holgado’s trip took them to Sidi Bouzid, the city in Tunisia where the first protests of the 2010 revolution were sparked by the death of Mohamed Bouazizi, a street vendor who set himself on fire after suffering police harassment for some time. Their report on what life is like in Sidi Bouzid was published in the Italian daily newspaper Domani and featured firsthand accounts from residents who lived through the tumultuous days of the revolution. Other stories on the economic crisis gripping the northern African country and the corruption of its institutions were published by RadioTelevisione Svizzera Italiana (RSI), El Salto, il manifesto, and FQ Millennium, the monthly magazine of the Italian newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano.

Garavoglia and Holgado live in Rome, producing videos, podcasts, and articles to sell to news outlets. However, Domani, RSI, El Salto, and il manifesto didn’t send them to Tunisia. They organized the trip themselves and paid for their reporting expenses with funds provided by the Centro di Giornalismo Permanente (CGP, Permanent Journalism Center), a collective of professional freelance journalists producing in-depth, long-form journalism. (Disclosure: Both authors of this piece are CGP members.) Garavoglia is a founding member of CGP, which started in 2018; Holgado joined in 2019.

As members of CGP, they are part of a community of freelance professionals who share ideas and work together on stories that would be too expensive and demanding for a single journalist to tackle. “We could have never paid the travel expenses just by selling the articles we were going to write while [in Tunisia],” says Holgado. “Associations such as CGP fill a void in the Italian media landscape. We pursue ambitious stories that legacy outlets often do not anymore, mostly due to budget cuts. Indirectly, we broaden the content that newspapers offer to their readers.”

“Associations such as CGP fill a void in the Italian media landscape. We pursue ambitious stories that legacy outlets often do not anymore, mostly due to budget cuts. Indirectly, we broaden the content that newspapers offer to their readers”

— Youssef Hassan Holgado

In Italy, a growing number of young Italian graphic designers, photographers, visual storytellers, and freelance journalists are joining forces in informal collectives, cooperatives, and commercial companies to collaborate with legacy news outlets. Their focus: longer-form articles and more in-depth pieces that established newsrooms don’t have the staff or budgets to cover.

The last decade saw a steep drop in newspaper sales and income from ads, a trend that has deepened the wage disparities between staff journalists and freelancers. According to Agcom, the Italian antitrust authority for the communication sector, more than four out of 10 journalists are freelancers. In its latest report, published in 2020, Agcom highlighted how nearly 63 percent of all journalists earn less than 35,000 euros per year. Of those, about 45 percent of freelancers and 50 percent of contractors (freelancers who have a contract with a news outlet) earn less than 5,000 euros per year. The profession is also aging. Forty percent of the journalists in Italy are older than 50, while 70 percent are over 40, according to the report. And, nearly three-quarters of journalists under 35 earn less than 20,000 euros per year.

As highlighted by Agcom’s report, the vast majority of people working in journalism, and particularly as staff editors in newsrooms, are over 40. This, along with the economic crisis and the impact of Covid-19, has created an almost overwhelming situation for younger, aspiring journalists. Insofar as young people want to pursue a career in journalism, they are compelled to work as freelancers. Lack of funds and logistical challenges are an everyday issue for freelancers, as they cannot rely on the financial backing, and technical know-how that would otherwise be provided by a newsroom.

Italy’s freelancer associations have become alternative models for the production of journalism. Here is a look at four organizations trying to support freelance journalists while also meeting urgent coverage needs.

Lettera22

Founded in 1993, Lettera22 is the first collective of independent journalists in Italy. The name comes from the portable typewriter produced by Olivetti in 1950. “It’s a symbol that contains our idea of journalism: reporting from the field, delving firsthand into the facts, wearing out one’s shoes, and explaining with clarity the complexity of what’s going on,” says Paola Caridi, one of Lettera22’s founders.

In the early 1990s, Italian freelancers were almost nonexistent. Most journalists either worked in a newsroom or as external partners with the expectation that they would eventually be hired, says Caridi. But when she and five colleagues working for the foreign desk of Avanti!, a historically socialist newspaper, were laid off, they decided to band together instead of leaving the profession. “We made the best out of a bad situation, and turned being made redundant into an opportunity,” Caridi says. “The association that we founded allowed us to keep working together, while remaining free from the constraints imposed by a newsroom.”

Lettera22 has a membership fee and collects a percentage of the payment members receive for the articles they publish. In exchange, members get to be part of a collective of expert journalists, trading contacts about outlets and sources, and can apply for grants reserved for associations.

The structure is very loose for the 13 members. “There is not an established hierarchy. Each role serves a purpose in our machine,” says Giuliano Battiston, Lettera22’s current director. In Lettera22’s original incarnation, each journalist covered a specific area of the world: Caridi focused on the Middle East, while the others focused on Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and China. “We published stories nobody else had, reporting from the heart of areas of conflict and capitalizing on our contacts with [non-governmental organizations] and [U.N.] agencies,” says Caridi. “We were among the first in Italy to cover the war in the Balkans or the coltan mines in Congo.”

After establishing itself with local newspapers that lacked international news, Lettera22 moved to wider-reaching national outlets, like L’Espresso, La Stampa, and Il Sole 24 Ore, as well as academic publications and books. “With time, outlets started relying more and more on the articles and news that we provided, and occasional relationships turned into regular ones,” says Caridi.

Among their collective efforts there are two books: “A Oriente del Califfo” (“East of the Caliph”), which explores the broader plan of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant to convert non-Arab Muslims to their cause; and “Sconfinate. Terre di confine e storie di frontiera” (“Boundless. The borderlands and their stories”), which focuses on the concept of borders, and on the similarities between communities whose shared trait is living close to a country’s border. They also co-organized a festival on foreign reporting called MIP, Il mondo in periferia (The world’s suburbs), last June in Rome.

Through its website, Lettera22 advertises its members’ articles published by legacy newspapers, and it publishes editorials and opinion pieces on the areas of the world its members cover. The website helps Lettera22 reach a wider audience and grow its brand. “We now have earned enough prestige on matters of foreign news and politics,” says Battiston, “that we don’t need to necessarily rely on the publication of our articles on legacy newspapers.”

Permanent Journalism Center

In 2018, about 20 former students at the Fondazione Basso’s journalism school in Rome were at a bar having a conversation so many in the industry have been having: Is there a solution for the precarious career situations in which many young journalists find themselves?

“The answer was the Permanent Journalism Center (CGP), found at the bottom of a bottle of beer,” jokes Matteo Garavoglia, who used CGP’s funding to report from Tunisia.

All of CGP’s members have interned at various Italian news outlets, increasing their disillusion with an industry that seems inaccessible to younger people. CGP started out with just eight founding members and has grown to 16, with most coming from the same journalism school its founders attended.

CGP’s members meet on a bi-weekly basis to discuss the association’s activities. They pitch ideas and decide as a team which ones to further develop. The members who show an interest in the project then form a team, deploying themselves to report on the story.

CGP’s membership fee is 10 euros per year, but the organization’s main sources of funding are monthly online workshops on journalism-related topics, such as how to write an investigative article, how to write about a specific area of the world, or how to produce a podcast. The workshops are taught by experts in the field and feature theory lectures and practical lessons. Enrollment fees average around a hundred euros, and workshop attendees range from freelance journalists seeking to broaden their skills to people outside the sector curious to know more about a specific topic.

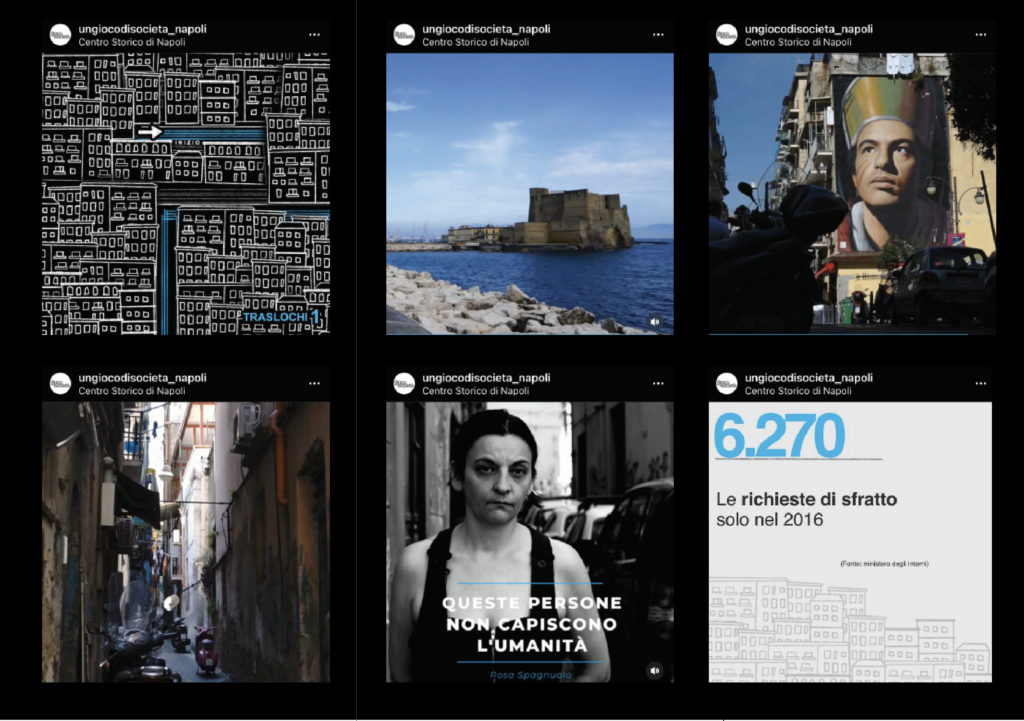

Among CPG’s published projects is “Un gioco di società” (A board game), a report on Instagram that analyzes the sociological, economic, and urban transformation of Italian cities that won the 2019 Roberto Morrione Prize for investigative journalism. The project focused on Naples, Rome, and Milan, highlighting how the development of Italy’s most populous cities is shaped to benefit hedge funds, international real estate firms, and digital short-stay rental platforms, often with the public sector’s complicity. The report borrows aspects of table-top games and integrates them into Instagram. Starting from the main account, the user is free to pick one of the three cities analyzed. From there, the user is redirected to the city’s Instagram account, beginning a journey that explains how each city has changed in recent years.

CGP, headquartered in Rome, opened an office in a co-working space in March 2020, shortly before Italy’s first coronavirus lockdown, so members had a place to collaborate.

“We did not have a newsroom, so we created one for freelancers,” says Elena Basso, another CGP founding member. “By working together, we were able to develop our professional skills and break the chains of the loneliness that yoked us.”

The Investigative Reporting Project Italy

Disillusionment with existing newsroom opportunities also prompted Giulio Rubino and Cecilia Anesi, two aspiring journalists who met in London in 2009, to found IRPI, The Investigating Reporting Project Italy, in 2012. IRPI is a collective of journalists focused solely on investigative journalism, funded through grants and donations from European foundations. “A systematic lack of funding was a longstanding issue for us,” says Rubino. “With time, we developed close relationships with foundations that grant us funds without tying any of it to a specific project. Within IRPI, we have people who both work solely on grant applications alongside the journalists who are then going to use those grants to develop journalistic reports.”

Investigative projects are planned collectively, with Anesi working as a supervisor. IRPI operates like any newspaper newsroom, with co-editors-in-chief Rubino and Lorenzo Bagnoli, six editors and reporters, and two contractors. The collective has its own online news outlet, IRPI Media, launched in 2020. IRPI is also part of two international investigative journalism consortiums — the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and the Global Investigative Journalism Network.

“Our ambition right from the beginning [was] to create an independent voice,” says Rubino. “We have now moved on from strictly selling our reports and investigations to legacy publications. We now have our own website. We would rather readers experience our work on our website rather than visit someone else’s.”

IRPI was the Italian partner in a lengthy investigation called OpenLux, coordinated by Le Monde, in which six news outlets uncovered the underground world of European finance, scrutinizing some three million documents and around 124,000 businesses. The project, published in February 2021, revealed how politicians, businessmen, and criminal organizations evade taxes by hiding their money in Luxembourg, where about 90 percent of companies registered there are controlled by entities outside the country.

FADA

In Niger, a fada is a place where unemployed men meet to socialize, discuss politics and social issues, form new relationships, and forge a sense of identity. Giacomo Zandonini, one of the few Italian journalists covering western Africa, thought it would be the perfect name for a journalism collective reporting from various parts of Africa not covered by Italian news outlets. Along with five other journalists scattered all over the world, Zandonini launched FADA in December 2020.

FADA has a horizontal structure, with each member having the same influence when it comes to pitching stories. The common thread connecting all FADA stories is social engagement; frequent areas of coverage include civil society, activism, migration, climate change, and social rights, with articles published in outlets like The National, the Guardian, and Al Jazeera.

FADA is mostly funded through grants and events designed to help freelance journalists — whether they are members of the collective or not — reporting from abroad. The organization helps to pay for insurance coverage and protective equipment when needed on assignment. When FADA journalists work in risky areas, the association’s network stays up to date on reporters’ whereabouts and intervenes to help when necessary.

“In the Italian media landscape, foreign reporting is left to underpaid freelancers … Ideally, our association represents a different model for foreign reporting to introduce higher quality foreign reporting”

— Giacomo Zandonini

During an event held in February 2021, FADA discussed how Italian news outlets are increasingly relying on freelancers because they cannot afford to pay foreign correspondents. But the economics don’t work for freelancers trying to make a living reporting from abroad. The “goal of our association is to promote a new way of reporting on foreign-related topics,” says Zandonini. “In the Italian media landscape, foreign reporting is left to underpaid freelancers. This leads to unnecessary rivalries and competition, which affects the quality of the journalism produced. Ideally, our association represents a different model for foreign reporting to introduce higher quality foreign reporting.”

Their idea of foreign reporting can be better understood by looking at two recent works of theirs: a long-form article on how Benin is becoming a major outpost of jihadist terrorist groups in Africa; and a documentary on the challenges that human rights advocates are facing in Iraq.

Andrea Iannuzzi, La Repubblica’s senior managing editor, maintains that news associations “will take up more and more space within the journalism sector” to fill the content gap left by journalism’s financial crisis. La Repubblica is not alone in relying on collaboratives for coverage. L’Espresso, one of Italy’s most influential weekly publications, has also published stories by organizations made up of freelance journalists. “Bigger, collective products equals more in-depth reporting,” says Beatrice Dondi, deputy editor of L’Espresso. Freelance collaboratives “greatly increase the quality of journalism content that a publication can present to its audience.”