EDITOR'S NOTE:

Shahla Sherkat received from the 2005 class of Nieman Fellows the Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism for covering politics and domestic abuse of Iranian women.Iranian journalists, like their peers everywhere, make choices and decisions reflecting their individual identities, exigencies of time and place, and available options. How each answers the question, “What made you a journalist?” will vary as much as the lives do of those asked to respond. Yet they reach common ground with the recognition of how few options any of them have.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Telling the Stories of Iranian Women’s Lives"

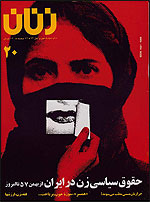

- Shahla SherkatI became a journalist by coincidence, when a college professor asked me to assist the founder and editor of a newly published magazine in need of help putting together an editorial staff. The magazine, Zanan (Women), was postrevolution Iran’s first feminist publication, launched with limited resources in a small room inside an office building. It was founded by Shahla Sherkat, a professional journalist and a feminist with religious beliefs. I was going to work temporarily until she hired her editorial team; however, when new staff was assembled, I stayed.

In spite of Iran’s political constraints and male-dominated media environment, Zanan grew rapidly. In a span of a decade, it attracted 20 journalists to its staff; many of these young journalists were turned into seasoned professionals trained in women’s issues. Domestically, Zanan became an example of the successful merging of journalism and women’s advocacy. Internationally, it turned into one of the more reliable sources of information regarding Iranian women’s issues.

While independent publications generally have a short life in Iran, Zanan enjoyed a longer run, largely because of Sherkat’s acumen in dealing with sociocultural and political taboos. On several occasions, Zanan was summoned to Iran’s press court, and the magazine was almost shut down three times. Some of its writers were banned from writing; others were imprisoned. Still, Zanan continued its remarkable journey.

In spite of all the difficulties and volatilities that characterized my professional life, I’ve never regretted becoming a journalist and working for Zanan. It’s where I grew up—as a journalist and as a person. My work with Zanan had taken me inside people’s homes and family courts, to the coroner’s office, police stations and mortuaries, where I came face to face with the hidden and blatant inequalities of Iranian women’s daily lives. I also became familiar with Iran’s Constitution and civil code in the search for sources of violence against women. And with Zanan, I sat in meetings, roundtables and interviews with experts looking for solutions.

Leaving Iran, Exploring the World

The day I joined the magazine, I was a young, inexperienced college student majoring in English with barely any knowledge of journalism. Twelve years later, when in 2004 I left to experience a new world, I was a feminist and a journalist on my way to begin a challenging and rewarding year as a Nieman Fellow.

Though I didn’t feel less capable than the other fellows, I was less vocal and more reserved. Looking back, I realize that I was in a state of shock, perhaps the shared experience of those who have lived in isolated societies for so long. I know I should have traveled more during that time, but working in Iran’s independent press did not provide me with enough savings to do so. Even if I had the money, getting the required traveling visas was an ordeal. (To come to the United States, even with a proper invitation from the Nieman Foundation, my visa was denied when I applied first through the American Consulate in Dubai. I had to postpone my fellowship for one year to secure a visa with the help of various channels.) There were also times that I had to forgo trips to professional conferences or workshops because I was afraid of political repercussions for the magazine or myself.

Communicating in another language can be painful, especially for a journalist whose main skill is connecting with others. So mostly as a fellow I became a listener. As soon as I had pulled my thoughts together and was ready to utter a sentence, the topic had moved in a different direction. How lucky I felt my Pakistani or South African colleagues were as they arrived speaking English well, while here I was, as someone who had majored in English and been a fairly good translator. I had no difficulty understanding people but, without having had a prior arena for practice at home or at work, speaking English was a chore.

The volume of one-sided news about Iran frightened me as well. It had never occurred to me that I also had to censor myself in the land of free press, lest I unwittingly reproduce the false and widely held clichés about my country. I read the news, listened to radio and television, and though I wanted to share my responses to it, instead I bristled.

More than classes at Harvard or discussions at the foundation, I benefitted from the companionship of other journalists from around the world. We got to know each other; as we listened to each other’s life stories, we found similarities, but differences, too. Such familiarity replaced my homesickness and awkwardness. Through our conversations, we were escorting each other to France, the United Kingdom, South Africa, places in the United States, Mexico—and Iran. My years of isolation were compensated, and my vision moved from the geography of Iran to that of the world.

It is now five years since I left Iran. I had several reasons for lengthening my stay. But the most important was unabashedly selfish; to take even more advantage of the opportunity afforded me. I knew once I went back, there would be almost no chance for yet another extended experience. Working conditions for the press were also becoming more and more difficult, including at Zanan. In 2008, after 16 years of existence, my professional home was banned by the Press Supervisory Board without any clear reason given. All efforts to lift the ban were fruitless. Even before that happened, I worried that no journalism jobs would be available for me if I returned.

By staying in the United States, I knew my life as a journalist would enter a lull. The loss of audience can be as much a threat to a journalist as lack of press freedom. I could have written for the Iranian exile press or U.S. government-owned news media that targets an Iranian audience. To not do this was a very difficult decision, but that’s what I chose. As I write now, I think of my colleagues in Iran and how the closure of Zanan changed their lives in ways that cut to the core of who they are and what they believe in.

Undoubtedly, these are wretched days for Iranian journalists. Some have chosen to live outside of the country, they hope temporarily; others had no choice but exile. Among those journalists who have stayed, a few have gone to prison, and some of those who are now free have no publications for which to work. I realize now that location has not made much of a difference for me. A reporter who has lost her audience or her publication, no matter how skilled and adaptive she might be, is still an unemployed journalist.

Roza Eftekhari, a 2005 Nieman Fellow, is a program assistant at the Eurasia Foundation in Washington, D.C..

Shahla Sherkat received from the 2005 class of Nieman Fellows the Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism for covering politics and domestic abuse of Iranian women.Iranian journalists, like their peers everywhere, make choices and decisions reflecting their individual identities, exigencies of time and place, and available options. How each answers the question, “What made you a journalist?” will vary as much as the lives do of those asked to respond. Yet they reach common ground with the recognition of how few options any of them have.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Telling the Stories of Iranian Women’s Lives"

- Shahla SherkatI became a journalist by coincidence, when a college professor asked me to assist the founder and editor of a newly published magazine in need of help putting together an editorial staff. The magazine, Zanan (Women), was postrevolution Iran’s first feminist publication, launched with limited resources in a small room inside an office building. It was founded by Shahla Sherkat, a professional journalist and a feminist with religious beliefs. I was going to work temporarily until she hired her editorial team; however, when new staff was assembled, I stayed.

In spite of Iran’s political constraints and male-dominated media environment, Zanan grew rapidly. In a span of a decade, it attracted 20 journalists to its staff; many of these young journalists were turned into seasoned professionals trained in women’s issues. Domestically, Zanan became an example of the successful merging of journalism and women’s advocacy. Internationally, it turned into one of the more reliable sources of information regarding Iranian women’s issues.

While independent publications generally have a short life in Iran, Zanan enjoyed a longer run, largely because of Sherkat’s acumen in dealing with sociocultural and political taboos. On several occasions, Zanan was summoned to Iran’s press court, and the magazine was almost shut down three times. Some of its writers were banned from writing; others were imprisoned. Still, Zanan continued its remarkable journey.

In spite of all the difficulties and volatilities that characterized my professional life, I’ve never regretted becoming a journalist and working for Zanan. It’s where I grew up—as a journalist and as a person. My work with Zanan had taken me inside people’s homes and family courts, to the coroner’s office, police stations and mortuaries, where I came face to face with the hidden and blatant inequalities of Iranian women’s daily lives. I also became familiar with Iran’s Constitution and civil code in the search for sources of violence against women. And with Zanan, I sat in meetings, roundtables and interviews with experts looking for solutions.

Leaving Iran, Exploring the World

The day I joined the magazine, I was a young, inexperienced college student majoring in English with barely any knowledge of journalism. Twelve years later, when in 2004 I left to experience a new world, I was a feminist and a journalist on my way to begin a challenging and rewarding year as a Nieman Fellow.

Though I didn’t feel less capable than the other fellows, I was less vocal and more reserved. Looking back, I realize that I was in a state of shock, perhaps the shared experience of those who have lived in isolated societies for so long. I know I should have traveled more during that time, but working in Iran’s independent press did not provide me with enough savings to do so. Even if I had the money, getting the required traveling visas was an ordeal. (To come to the United States, even with a proper invitation from the Nieman Foundation, my visa was denied when I applied first through the American Consulate in Dubai. I had to postpone my fellowship for one year to secure a visa with the help of various channels.) There were also times that I had to forgo trips to professional conferences or workshops because I was afraid of political repercussions for the magazine or myself.

Communicating in another language can be painful, especially for a journalist whose main skill is connecting with others. So mostly as a fellow I became a listener. As soon as I had pulled my thoughts together and was ready to utter a sentence, the topic had moved in a different direction. How lucky I felt my Pakistani or South African colleagues were as they arrived speaking English well, while here I was, as someone who had majored in English and been a fairly good translator. I had no difficulty understanding people but, without having had a prior arena for practice at home or at work, speaking English was a chore.

The volume of one-sided news about Iran frightened me as well. It had never occurred to me that I also had to censor myself in the land of free press, lest I unwittingly reproduce the false and widely held clichés about my country. I read the news, listened to radio and television, and though I wanted to share my responses to it, instead I bristled.

More than classes at Harvard or discussions at the foundation, I benefitted from the companionship of other journalists from around the world. We got to know each other; as we listened to each other’s life stories, we found similarities, but differences, too. Such familiarity replaced my homesickness and awkwardness. Through our conversations, we were escorting each other to France, the United Kingdom, South Africa, places in the United States, Mexico—and Iran. My years of isolation were compensated, and my vision moved from the geography of Iran to that of the world.

It is now five years since I left Iran. I had several reasons for lengthening my stay. But the most important was unabashedly selfish; to take even more advantage of the opportunity afforded me. I knew once I went back, there would be almost no chance for yet another extended experience. Working conditions for the press were also becoming more and more difficult, including at Zanan. In 2008, after 16 years of existence, my professional home was banned by the Press Supervisory Board without any clear reason given. All efforts to lift the ban were fruitless. Even before that happened, I worried that no journalism jobs would be available for me if I returned.

By staying in the United States, I knew my life as a journalist would enter a lull. The loss of audience can be as much a threat to a journalist as lack of press freedom. I could have written for the Iranian exile press or U.S. government-owned news media that targets an Iranian audience. To not do this was a very difficult decision, but that’s what I chose. As I write now, I think of my colleagues in Iran and how the closure of Zanan changed their lives in ways that cut to the core of who they are and what they believe in.

Undoubtedly, these are wretched days for Iranian journalists. Some have chosen to live outside of the country, they hope temporarily; others had no choice but exile. Among those journalists who have stayed, a few have gone to prison, and some of those who are now free have no publications for which to work. I realize now that location has not made much of a difference for me. A reporter who has lost her audience or her publication, no matter how skilled and adaptive she might be, is still an unemployed journalist.

Roza Eftekhari, a 2005 Nieman Fellow, is a program assistant at the Eurasia Foundation in Washington, D.C..