“They are pictures from the heart, of devastated buildings and of devastated people. They are images of us—the living—trying to mourn our invisible dead.”

These words—part of a reflection on the connections we’ve made with the vast array of images from September 11, 2001—belong to photographer, author and former newspaper editor Frank Van Riper. In an essay he wrote to explore the impact photographs have on us and the impact this event had on the medium, Van Riper urges us to think about how “photography’s power to move immediately from the cerebral to the visceral” has shaped how we’ve been affected by what we’ve seen. He writes about early attempts by officials to not allow photographers to be at Ground Zero, but then conveys the thoughts of two photographers, Peter Turnley and Stan Grossfeld, who were there. “There will always be those who view journalists as voyeurs and parasites, but these two shooters give powerful voice to the compelling need of journalists, not only to do their jobs, and thereby bring an important story to the world, but also to offer up at a terrible time what skills they have—as reporters of words and pictures—in the collective and somber effort of rebuilding,” Van Riper writes.

"When I first saw Ground Zero, I literally felt as though I had been punched in the stomach. In this photograph, a firefighter at Ground Zero throws up his hands in despair." Photo by Stan Grossfeld.

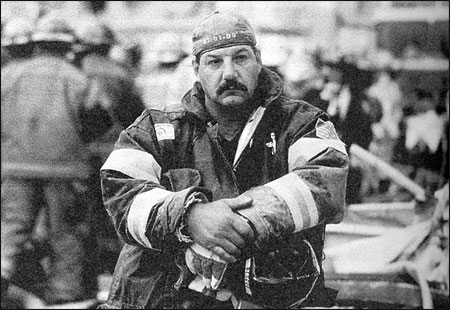

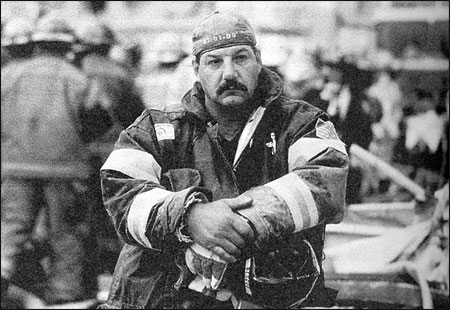

"What moved me was a sense of a life being transformed by an experience in a way that there was no going back. You could never be the same person after that night. And this man will certainly never be the same person." Photo by Peter Turnley.

In reading Todd Gitlin’s book, “Media Unlimited,” journalist Ellen Hume emerged disheartened by the American media culture he describes and by the apparent lack of concern Gitlin expresses about the direction in which it seems headed. As Hume writes, “He portrays media as one might describe a prostitute, offering sensual engagement that demands nothing and means nothing except a moment’s pleasure and a bit of commerce.” Hume’s displeasure is amplified by how Gitlin sees journalism’s place in this media environment: “Trying to bear witness and report the facts seems pointless in Gitlin’s world,” she writes, “since the media audience is not trying to construct meaning, but to flee from it.”

Jim Bellows’ retrospective book, “The Last Editor,” provides an apt contrast to Gitlin’s futuristic perspective. As the Nieman Foundation’s special projects director Seth Effron observes, Bellows’ memoir reminds us “that even as newsroom executives are mired in ledger balances and spread sheets, it is still editors and reporters—and fine storytelling—that are the heart and soul of journalism.”

These words—part of a reflection on the connections we’ve made with the vast array of images from September 11, 2001—belong to photographer, author and former newspaper editor Frank Van Riper. In an essay he wrote to explore the impact photographs have on us and the impact this event had on the medium, Van Riper urges us to think about how “photography’s power to move immediately from the cerebral to the visceral” has shaped how we’ve been affected by what we’ve seen. He writes about early attempts by officials to not allow photographers to be at Ground Zero, but then conveys the thoughts of two photographers, Peter Turnley and Stan Grossfeld, who were there. “There will always be those who view journalists as voyeurs and parasites, but these two shooters give powerful voice to the compelling need of journalists, not only to do their jobs, and thereby bring an important story to the world, but also to offer up at a terrible time what skills they have—as reporters of words and pictures—in the collective and somber effort of rebuilding,” Van Riper writes.

"When I first saw Ground Zero, I literally felt as though I had been punched in the stomach. In this photograph, a firefighter at Ground Zero throws up his hands in despair." Photo by Stan Grossfeld.

"What moved me was a sense of a life being transformed by an experience in a way that there was no going back. You could never be the same person after that night. And this man will certainly never be the same person." Photo by Peter Turnley.

In reading Todd Gitlin’s book, “Media Unlimited,” journalist Ellen Hume emerged disheartened by the American media culture he describes and by the apparent lack of concern Gitlin expresses about the direction in which it seems headed. As Hume writes, “He portrays media as one might describe a prostitute, offering sensual engagement that demands nothing and means nothing except a moment’s pleasure and a bit of commerce.” Hume’s displeasure is amplified by how Gitlin sees journalism’s place in this media environment: “Trying to bear witness and report the facts seems pointless in Gitlin’s world,” she writes, “since the media audience is not trying to construct meaning, but to flee from it.”

Jim Bellows’ retrospective book, “The Last Editor,” provides an apt contrast to Gitlin’s futuristic perspective. As the Nieman Foundation’s special projects director Seth Effron observes, Bellows’ memoir reminds us “that even as newsroom executives are mired in ledger balances and spread sheets, it is still editors and reporters—and fine storytelling—that are the heart and soul of journalism.”