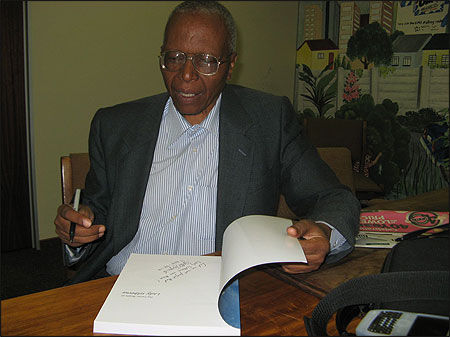

John Mojapelo, NF ’79, inscribes his memoir, “The Corner People of Lady Selborne,” published last year.

My Nieman class (1979) included two fellows from South Africa: John Mojapelo and Donald Woods. Getting to know them while studying the nature of prejudice kindled an interest in visiting that country, one I was finally able to fulfill earlier this year during an academic sabbatical.

In 1978, John was on leave from his job as a reporter for The Rand Daily Mail. Donald had been editor of the Daily Dispatch in East London, where he became friends with the anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko. Donald uncovered evidence that torture in police custody led to Biko’s death. After these stories were published, he and his family were threatened. The South African government “banned” him for five years, and he fled the country with his wife and children. Donald died in London in 2001, but earlier this year I was able to visit with John, who is a lawyer, and his wife, Elizabeth, a school principal, in Lady Selborne, west of Pretoria. It would be “un-African” to meet in a restaurant, John assured me, and so they prepared a traditional braai for me at the energy-efficient home they built on repatriated land once seized from the Mojapelo family and thousands of others under the apartheid government’s Group Areas Act.

I spent more than four weeks in South Africa, writing about women in leadership roles, and meeting people, including as many Niemans as possible, in Johannesburg, Durban, the Eastern Cape, Stellenbosch, Cape Town, plus rural and township settlements in between.

A Question of Leadership

In all of those places, I saw South Africans reading newspapers. Thabo Leshilo, NF ’09, who was named the first public editor of Avusa Media, which publishes the Sowetan, Sunday World, and the Sunday Times, told me why. “We lag behind the U.S. in terms of technological developments driving newspapers into bankruptcy,” he said. “Internet penetration is very negligible and the vast majority of the populace is not techno-savvy enough to ditch newspapers.”

I also saw plenty of people armed with mobile devices so the pressures on print media are intensifying. For now, however, “newspapers remain powerful in South Africa and their views matter,” Thabo told me. He cited the case of Julius Malema, president of the African National Congress (ANC) Youth League, who is under investigation for local government contracts awarded to his company that, according to Thabo, performed “shoddy work building bridges and roads. These have had to be redone, costing the taxpayer more. This [rebuilding] would not have happened had the media not exposed the shenanigans.” News stories when I was in the country accused Malema of interfering in the delicate diplomacy between South Africa and Zimbabwe and inciting anti-white violence by repeatedly singing a song that literally translates into “Kill the Boers [farmers].”

I asked Zwelakhe Sisulu, NF ’85, once a crusading journalist and later the first black to head the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), about the apparent absence today of idealistic leaders of the caliber of Archbishop Desmond Tutu or Nelson Mandela. Zwelahke and I met informally at Lippmann House in 1985. The next time I saw him, he was greeted by wild applause as he triumphantly entered Harvard’s Sanders Theater during the Nieman’s 50th anniversary celebration in 1989. He had been in detention in South Africa; it took the intervention and pressure of influential Americans to get him released, and few in the room that evening were sure that he would show up.

Today Zwelakhe is a prosperous entrepreneur. His sister, Lindiwe, is defense minister; his brother, Max, is speaker of the National Assembly. As he reflected on my leadership question, he noted that his late father Walter, who cofounded the ANC Youth League, and Mandela were products of missionary schools. Each was brought up with a strong moral code, which sustained them during long imprisonments. Zwelahke credits his mother, Albertina, with holding many families together while parents were jailed, banned and exiled.

“Our home was really a community center,” he recalls. People left clothes to help out the families, so he found himself as a boy literally in the “big shoes and big suits” of struggle leaders. With the clothes came stories: “This was so-and-so’s who was sentenced … .” Life was hard, but inspiring. “It was not just the sense of the extended African family, but the extended ANC family,” he said.

After Mandela was released from prison, he asked Zwelahke to leave the New Nation newspaper he’d founded and join him as his communications liaison on his world tour. In 1993, the ANC tapped him to transform the SABC from a tool of apartheid into a true public broadcaster to help the country prepare for its first democratic elections a year later. South Africa has 11 official languages, one of many logistical and philosophical challenges he faced in that role. He is still involved in broadcasting, through Urban Brew, which is the biggest content provider for SABC, and a number of other industries, including book publishing, solar energy, and mining. A project close to his heart is Soweto TV, what he calls “the first community television channel in this country.”

“A lot of our presenters are kids who live off the streets,” he said, but the endeavor is not social work. “I would say in the next 12 months Soweto TV will be financially viable.”

Thabo Leshilo, NF ’09, is the first public editor of Avusa Media.

A Rallying Point

The effects of apartheid are still harshly apparent in the huge disparities in economic well-being, educational attainment, and job prospects. Yet the cultural context of South Africa’s young people—the Born Free—is quite different from that of their elders. The generation who grew up during the struggle had many “assembly points”—in prisons and in impassioned strategy sessions, for example. Today’s young people have none. A program of national (not military) service might be a way to teach job skills, teamwork and discipline to this younger generation, creating a common purpose. Perhaps, Zwelahke suggested, Soweto TV and similar ventures he plans to launch in other urban centers could be future community assembly points.

He described Mandela’s leadership as “this big tree under whose shade we all lived,” while acknowledging President Jacob Zuma’s charisma. But the country will not advance significantly without creating more jobs. “You need a leader who is going to be very sophisticated economically,” he said.

“One of the great things about the new South Africa is that media and journalism are thriving,” said Zwelahke, who praised the diversity of views and choices, even if, as he acknowledges, the quality is not always the best. He is confident that expanded broadband capacity and more access will accelerate change. He commended today’s journalists, for standing up “to all sorts of threats, direct and implied, without buckling under.”

Nancy Day, a 1979 Nieman Fellow, has chaired the Journalism Department at Columbia College Chicago since 2003. Previously, she was an associate professor at Boston University and a journalist in Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.