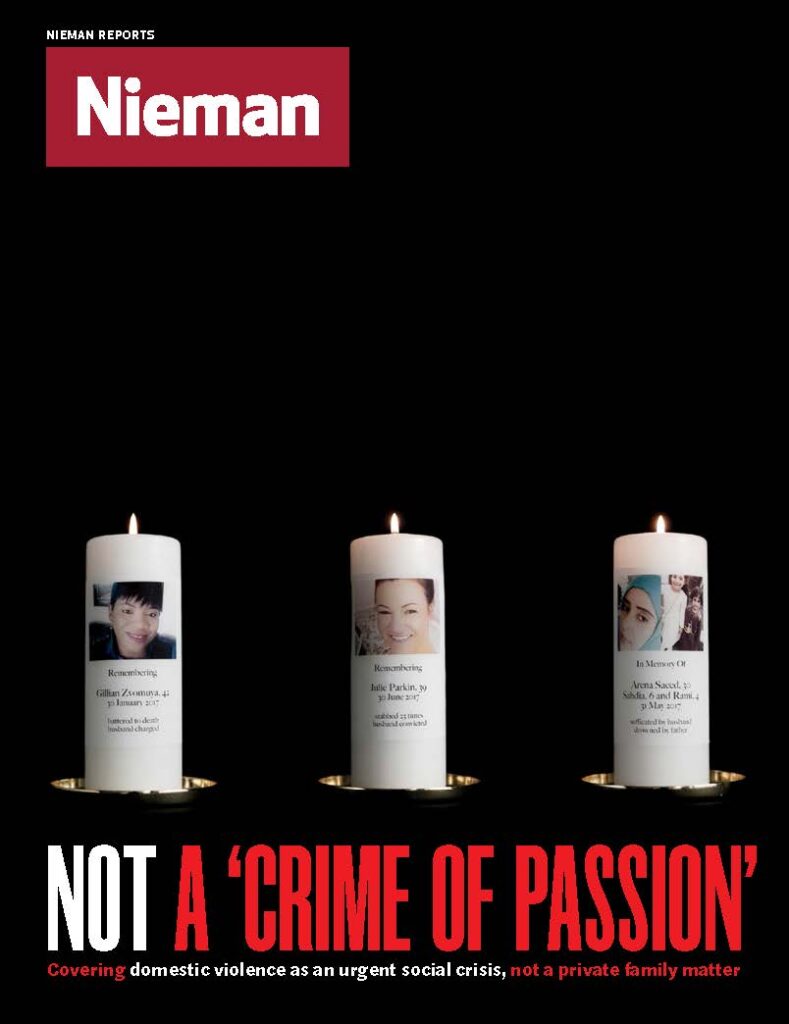

While the #MeToo movement has highlighted the need to take sexual assault seriously, there hasn’t been the same kind of cultural reckoning concerning domestic violence. A study by James Alan Fox and Emma E. Fridel at Northeastern University found that 45% of women murdered in the U.S. between 2007 to 2016 were killed by an intimate partner. The statistic for men? Just 5%.

Too often, domestic violence has been covered as a private family matter, rather than as an urgent social crisis. Today more journalists are reporting with nuance and sensitivity on the complexities of the problem.

In their press freedom ranking of 180 countries, Reporters Without Borders this year named Norway its valedictorian. So free is the country from censorship, political pressure, or violence against journalists, that the headline atop the annual report’s section on Norway read, “Faultless or almost.”

So I was surprised, during a recent visit from several Norwegian journalists, by a conversation about the demagoguery and denunciations of journalism emanating from U.S. politicians. It was dangerous, I agreed, and encouraging that countries like theirs persisted in defending press values.

“Yes,” said the woman from Norway, “but this rhetoric, it’s contagious.”

As President Trump and his allies have amplified their attacks on journalism, the impact has spread beyond the U.S., with even stable democracies wary of its polluting influence. This rhetoric is contagious, and is now one of our leading cultural exports.

While the nation’s own press freedom ranking fell to 48—the result of physical attacks, the deadly shooting at the Annapolis Capital Gazette, and threats requiring some media companies to hire security guards for their reporters—Trump has found an eager chorus among other world leaders and applauded their ominous echoes.

The president’s forgiving embrace of Saudi authorities in the wake of columnist Jamal Khashoggi’s murder and dismembering last fall marked a new low. “The level of violence used to persecute journalists who aggravate authorities no longer seems to know any limits,” said Reporters Without Borders. Gone is the historic role that U.S. presidents played in defending the essential role of journalism in a democracy, replaced by White House succor for autocrats and authoritarians seeking to silence independent reporting. We are now—in the words of Stalin, Mao, Nazi propagandists, and Trump—“enemies of the people,” language weaponized during some of history’s darkest hours.

As Trump and his allies have amplified their attacks on journalism, the impact has spread beyond the U.S. This rhetoric is contagious, and is now one of our leading cultural exports

“Trump inhabits the global showcase,” said Salvadoran author and journalist Oscar Martinez. “In attacking the U.S. press, he attacks all of the press and puts it at risk.”

The kinship Trump exhibits for fellow enemies of independent reporting was evident during this March exchange in Washington with newly-elected Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.

Bolsonaro: “Brazil and the United States stand side by side in their efforts to ensure liberties and respect to traditional family lifestyles, respect to God our creator, against the gender ideology or the politically correct attitudes and against fake news.”

Trump: “I’m very proud to hear the president use the term ‘fake news.’”

Bolsonaro wasn’t bluffing and in his brief tenure has used social media to attack reporters whose coverage he doesn’t like, suppressed government advertising to weaken the press, and, most recently, threatened American journalist Glenn Greenwald with imprisonment for stories questioning the conduct of Brazil’s justice minister.

Some of journalism’s harshest antagonists—Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, Myanmar state security officer U Kyaw San Hla, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu among them—have all parroted Trump’s cries of “fake news” to advance their own press wars.

“[I] would like to send a message to the president that your attack on CNN is right,” said Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, dismissing reports of corruption and sex trafficking in his country. “American media is very bad.”

Said a shameless al-Assad, one of the world’s most murderous dictators: “We are living in a fake-news era.”

One of the unfortunate consequences of this hostile environment is that it compromises the possibility of genuine reflection about journalism’s failings. In the U.S., the “fake news” complaints clotting public discourse are now so suspect, and the skepticism from journalists so heightened, it is hard to imagine how the conversation is bridged. Honest response to legitimate criticism is difficult when the criticism comes in a torrent of false accusations. It’s like trying to separate raindrops.

I recently watched a video of a 1962 Oval Office interview that three network news reporters held with President John F. Kennedy. The civility is nearly unrecognizable and a reminder of how distorted our discourse has become. Kennedy, like every president before and since, took umbrage at some White House coverage. He refers to the press as “abrasive” and implies that news can be distorted for political purposes. But his fundamental respect for its role in a democracy is sufficiently strong that he says Nikita Khrushchev, then premier of the Soviet Union, is disadvantaged without it.

“Even though we never like it, and even though we wish they didn’t write it, and even though we disapprove, there isn’t any doubt that we couldn’t do the job at all in a free society without a very, very active press,” Kennedy said.

How do we get back to that discussion? Are we as journalists doing enough in our work and in our communities to advance that conversation and earn that respect?

Although there are countries that never tolerated an independent press, the retreat in places that once did have such a press shows how precipitous the change can be. Hungary’s free fall in world press freedom rankings—down 14 positions to 87 this year—mirrors the country’s overall decline across other measurements of democratic health, including treatment of the courts, schools, and religious organizations.

If you seek a playbook for how to weaken and eventually erase a free press, turn to Hungary since the 2010 election of Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party. The harassment and shuttering of independent media alongside the creation of a pro-Orban consortium of private TV, radio, newspapers, and websites have virtually strangled critical voices.

“When Mr. Orban came to power in 2010, his aim was to eliminate the media’s role as a check on government,” a former public radio anchor told The New York Times. “Orban wanted to introduce a regime which keeps the facade of democratic institutions but is not operated in a democratic manner—and a free press doesn’t fit into that picture.”

Last year I visited Warsaw’s Gazeta Wyborcza, a newspaper founded in the late ’80s out of the Solidarity movement. After years of success, the independent daily has emerged as one of the prime targets of President Andrzej Duda and his Law and Justice Party, elected in 2015. Like Hungary’s Orban, Duda and party leaders have sought to mute the press as part of their dismantling of Poland’s hard-won, post-Soviet democracy.

In doing so, Duda has displayed a familiar fealty to Trump, earning him a description in Foreign Policy as “perhaps the savviest of all Trump’s ego massage therapists.” Using Trump’s preferred communication channel, Duda has tweeted his alignment: “President Trump @realDonaldTrump just stressed again the power of fake news. Thank you. We must continue to fight that phenomenon. Poland experiences fake news power first hand. Many European and even US officials form their opinions of PL based on relentless flow of fake news.”

Jerzy Wojcik, publisher of the Gazeta Wyborcza, and Jarosław Kurski, the deputy editor-in-chief, described a relentless government campaign of economic suffocation. They say this has included stripping traditional government advertising from their pages; diminished access for the paper to the national network of government-controlled gas stations (long a source of single-copy newspaper sales); and government pressure on private industry to pull advertising.

Wojcik said the paper lost approximately $5 million during the new government’s first year and had to lay off 170 employees.

“Censorship would be too obvious,” said Wojcik. “The main strategy to kill us is to kill our revenues.”

The newspaper has been the target of organized protests, including one outside the building that began with a priest performing an exorcism of the Gazeta Wyborcza. “What does it mean when people are shouting and singing and praying for your soul?” Wojcik asked. “We give you this description as an example that there is no red line, there are no limits.”

The paper has also been attacked by the government-controlled State TV Network, run by Jacek Kurski—the brother of Gazeta Wyborcza’s deputy editor. What is that like for you? I asked him. “Not good,” Jaroslaw Kurski said. “We mostly don’t talk anymore, only about our mother who died a couple of years ago.”

The paper is racing against time and government forces to create new, more lucrative subscription models and increase revenue from other company enterprises, including cinema, book publishing, and outdoor advertising. They have also joined with a European news consortium to share stories without cost.

“If you want to save democracy,” said editor Kurski, “you first must save yourself.”

Wojcik and Kurski were almost apologetic at one point, saying they don’t want to sound like they’re complaining, even as they describe journalism as “the last obstacle” to authoritarianism in Poland.

“I wake up here, I read the news from Poland and around the world, and think no, no, no, no,” said Wojcik, with a resigned smile. “But next I drink a coffee, smoke a cigarette, and say, ‘Okay, try to do something good, something to make a difference.’”