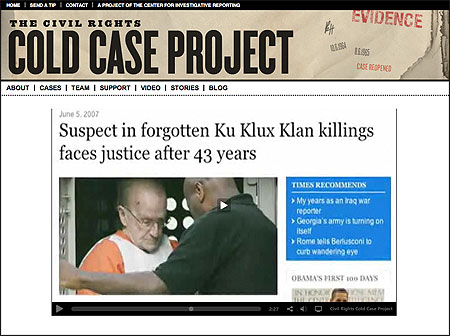

After a filmmaker and victim’s brother located James Ford Seale, he was prosecuted on kidnapping charges in connection with two deaths.

When I give talks about journalists revisiting unsolved murders from the civil rights era, the questions sometimes begin with a short one: "Why?"

Why is it so important? Why would a reporter choose to return to those discomforting times when blacks rightfully feared the Ku Klux Klan's firebombings and abductions, tortures, castrations and murders? Why is what happened then considered news today? Why stir up memories of events that were long ago put to rest? When a reporter tracks down a frail 80-year-old former Klansman and confronts him with the brutality of his past, when he is handcuffed and taken into court, aren't we putting at risk the racial healing achieved in the intervening decades?

Fortunately I have answers, and sometimes I need to use all of them before the "whys" wither away.

First, I offer an observation: As a people, we've decided that first-degree murder is a crime for which there is no statute of limitations. In every state, law enforcement can pursue a murderer until his dying breath, without exception. There is a reason for that. No person involved in murdering another should go to bed at night without worrying about whether he or she will be brought to justice the next day.

The "cold" cases we're pursuing belong to a genre of criminality that went beyond a few disconnected acts of violence. Reporters and lawyers investigating murders from the era of the civil rights movement encounter—as the Federal Bureau of Investigation did many years ago when its investigations frequently went unprosecuted—webs of names that appear again and again. They identify violent Klansmen who operated with the knowledge of law enforcement, legislators, mayors and governors, often with their participation and protection. The Klan—and its virulent spinoffs—was organized homegrown terrorism, more pervasive, enduring and deadly than anything this nation has known.

During the past 40 years our nation, at the federal and state levels, has reaffirmed its disdain for three kinds of criminal behavior characteristic of the Klan: organized crime, terrorism and hate crimes. Not allowing these unprosecuted cases to vanish—or those who committed these crimes to die without pursuit—fulfills that intent to track down and prosecute haters and terrorists. These crimes are so egregious and they are so woven into the context of who we Americans are today that we're interested in telling the stories even when there is no living perpetrator.

Memory and Healing

The South is a region built atop the toxic gases of suppressed memory and the restless bones of unresolved history. Some believe that drilling into the untold stories of that history will rupture a seal and release a new wave of hate. When Thomas Moore and filmmaker David Ridgen arrived in Meadville, Mississippi in 2005 to investigate the 1964 Klan murder of Thomas's brother Charles E. Moore and his friend Henry H. Dee, they visited weekly newspaper editor Mary Lou Webb. "That was years ago," she said, stretching out the word "years." "People have moved on. It doesn't do any good. And it's not going to do that dead man any good, for his ancestors [sic] to get in a squabble with the whites again."

Is Webb right? I come across people who find comfort in such beliefs. "Yes," they seem to be thinking, "we are a better people now. We're past that. We'd never let that happen again." But many more seem to understand that "we" are inheritors of a deeply divided nation that held and still holds vastly different perspectives on what it takes to achieve justice and freedom.

Many black families in the South—or surviving members of families who lived there in the mid-20th century—still do not know who killed their father, mother, grandfather, uncle, brother or sister. They live with the unspeakable grief of an unexplained loss. On our Civil Rights Cold Case Project website, a four-minute video speaks to the pain of this enduring loss: Wharlest Jackson, Jr., now in his 50's, weeps as he recalls the day in 1967 when he came upon his father's truck shredded by a bomb, his father RELATED ARTICLE

“A Father’s Life Tugs His Son to Revisit Unsolved Crimes”

- Ben Greenberginside, dead. The now-grown children of Clifton Walker, murdered in southwest Mississippi in 1964, speak of being sickened by knowing that for 47 years white people have been carrying the secret their family may never learn—the identity of the people who killed their father.

The families aren't seeking revenge. They just want to know. "Wouldn't you want to know who killed your father?" asked Jackson. "Everybody would."

Doug Jones, like me a white guy from Alabama, spent several years as the United States attorney in Birmingham. In 2001 and 2002, he served as a special prosecutor in state court against two Klansmen who had escaped prosecution for nearly 40 years in the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church that killed four little girls. These were long, difficult, costly prosecutions of two miserable, sickly, old men who had essentially disappeared from society.

Through the years, when challenged to justify his pursuit and prosecution of old Klansmen, Jones answered by asking his questioners to put themselves decades into the future and think about whether the pursuit and prosecution of those who murdered Americans in acts of terrorism in our time should go forward. When I hear this, I think of the late Simon Wiesenthal, the indefatigable Nazi hunter. "When history looks back," he once said, "I want people to know the Nazis weren't able to kill millions of people and get away with it."

It is not too late for something lasting to come from pursuit of these cases. Embedded in them are the seeds of racial reconciliation. Those who work on these cases—journalists and prosecutors—have seen it time and again.

In the Dee and Moore case, Charles Marcus Edwards, a former Klansman who was involved in beating the two men but not their murder, testified in federal court against James Ford Seale, a former Klansman many people had believed was dead. When Edwards finished the testimony that ultimately convicted Seale, he surprised the courtroom by apologizing to the families of the victims and asking forgiveness. The next day, with David Ridgen's video camera capturing the encounter for his Canadian Broadcasting Corporation documentary, "Mississippi Cold Case," Thomas Moore visited Edwards to thank him.

"It took a big man to do what you did yesterday," Moore said.

"I am, I am truly sorry, fella," Edwards said. He looked tense, apprehensive and uncertain what Moore might do.

"I appreciate what you did." Moore added. "I stated this last week, that I wanted to move on with my life."

"You did right."

"And I believe in the same God that you believe in," Moore said. "In the 18th chapter of Matthew, Peter asks, 'How many times should you forgive your brother?' "

Edwards relaxed, his face showed recognition of the passage, and his lips began to move as Moore continued: "And he answered, 'I will forgive him seven times.' But Jesus Christ said, 'No, not only seven times … ' "

Edwards elevated his voice and joined Moore in saying aloud, in unison, "… but 77 times seven.' "

Moore extended an open hand, met Edwards's hand, and said, "So you are forgiven."

Justice prevailed in that case because Ridgen, his camera rolling, took Moore back to Mississippi, found Seale alive, and got Edwards to tell the truth. Journalism, at its core, is about accountability, and reporters, at their best, are pursuers of the truth, no matter how long it has been hidden. That is why they do it.

Hank Klibanoff, the James M. Cox, Jr. Professor of Journalism at Emory University, is managing editor of the Civil Rights Cold Case Project. He is coauthor with Gene Roberts, a 1962 Nieman Fellow, of "The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation," which won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for History.