I was done. Absolutely done with writing, and especially done with writing books. This was in 2008, and I had just finished my book “Rin Tin Tin.” It was a story of the most famous dog in Hollywood, and it had grown into a convoluted, complicated tale that spanned a century and put me in contact with some of the most ornery subjects I’d ever encountered. And that was just the humans! The whole thing had taken me seven years and, quite honestly, it wore me out. In my postpartum exhaustion, I made the decision that I just couldn’t, wouldn’t, do it again.

Of course, I’m a sucker for books. I grew up in libraries, or at least it feels that way. I grew up in the suburbs of Cleveland, just a few blocks from a branch library, and from the time I was a toddler, my mom and I would go there at least once or twice a week. The library might have been the first place I was ever allowed to wander on my own, but the magic of the experience was inextricably linked to spending this almost sacred time with my mother.

She loved libraries. On the ride home, each time, we would have a solemn conversation about the order in which we would read our books and how we would pace ourselves during the charmed, evanescent period until the books were due. We both thought the branch librarians were beautiful. For a few minutes, we would discuss their beauty. My mother would also mention that if she could have chosen any profession at all, she would have chosen to be a librarian, and we would grow silent as we both considered what an amazing thing that would have been.

I loved books so much that I started writing them as soon as I could lift a pencil. My first book was called “Herbert the Near-Sighted Pigeon,” a stirring narrative about a tiny pigeon who was bullied by his brother and sister because of his small stature and his large glasses. Spoiler alert: He meets a bespectacled owl, who coaches him on witty retorts to bullies.

Being a writer was all I ever wanted to be.

My parents, though, were wary. They were products of the Depression, and they viewed the notion of writing as a profession with the kind of dread they might have felt if I had planned to be a professional tightrope walker. My father, who was a lawyer, urged me to go to law school, the inevitable route back then for English majors. He said if I wanted to try writing, that was an option, but a law degree would give me something to “fall back on.” With unearned bravado, I told him I didn’t plan on falling back.

I charged ahead, convinced that I could be, would be, a writer. And after some years writing for alternative newsweeklies and Sunday magazines, I was seized with the idea that I could write a book, and, lo and behold, I did it. Then I wrote another, and another. After each one, my parents congratulated me, and then my father would pull me aside to suggest that it wasn’t too late for me to go to law school.

After my third book was published, I told him, “Dad, I actually think it IS too late to go to law school.” One day, when I was particularly frustrated while working on “Rin Tin Tin,” and wondering if maybe I should have gone to law school, my dad, who was then almost ninety years old and still working as a lawyer, confessed to me that he had always wanted to be a writer.

Writing books is not easy, but I loved it. Each one is like a marriage. When I finished “Rin Tin Tin,” after what felt like a bit of agony, I was proud, but I also felt — perhaps like anyone who has been married six times — that maybe I just couldn’t get married again.

But the problem with being a writer is … you’re a writer. Stories stalk you. Stories beguile you. They bewitch you. It’s not easy to fend them off, even when you’ve vowed you will.

One day, a year after “Rin Tin Tin” was published, I stopped in at the library. This was an experience I had had hundreds of times before, but that time, something in my brain activated. Wow, I thought, libraries are so interesting! I wonder how they work, and I wonder what it’s like day-to-day in a library. I love to examine the inner workings of familiar things, and what could be more familiar than a library? But — wait. No. I took a deep breath. I thought, OK, it’s a great story, but not for me. But damn, what a good idea for a book.

Stories stalk you. Stories beguile you. They bewitch you. It’s not easy to fend them off, even when you’ve vowed you will.

Fast forward a few years: My husband and I have moved to Los Angeles. Our son started kindergarten, and right away, he had homework, to interview someone who worked for the city. I suggested he interview a garbage collector. He, being smarter than I am, suggested he interview a librarian. So off we went to our local branch library, in Studio City, California. The minute we walked in, I was flooded with those memories of going to the library with my mother.

Even though the building in Studio City was very different from my local library in Shaker Heights, Ohio, everything about it felt familiar — the hush in the room; the flyers on the bulletin board fluttering in the breeze; the wide worn desks; the sense that things were happening, words were being consumed, thoughts were percolating. The sense of familiarity hit me so hard that I almost gasped.

And then I thought, what a great idea for a book. But no. No!

Sometime after that trip to the library with my son, I met Ken Brecher, the head of the Los Angeles library foundation. He asked me to speak at one of the foundation’s luncheons. As a thank you, he wanted to give me a tour of the downtown library. (I was excited because I didn’t know L.A. had a downtown.)

The day of the tour, I drove to the library. Even from a distance, I was smitten. It’s a marvelous building — it looked like the architect had fallen asleep with a book about King Tut under his pillow and then woke up and designed it. Carved into the exterior surfaces was an assortment of history’s greatest observations about reading, books, knowledge, ideas — as I circled the building, I read it, almost as if it itself were a book. Ken and I walked through the building, and at every turn he told me about various patrons and librarians and the upheavals and challenges the library had weathered over the decades. It was like being on the best first date ever; every detail fascinated me, every row of books looked inviting.

When we reached the fiction department, Ken stopped in front of a shelf, rummaged around a bit, and then pulled out a book. He held it up and took a deep, deep whiff of it, and held it out towards me. I was stupefied. Was I supposed to sniff it, too? Was this an L.A. thing, to smell books? After a moment, he said, “You know, you can still smell the smoke in some of them.”

“Did they…. Did they used to let people smoke in the library?”

Ken scoffed at me and said, “No! Smoke from the fire!”

I stammered. “What… what fire?”

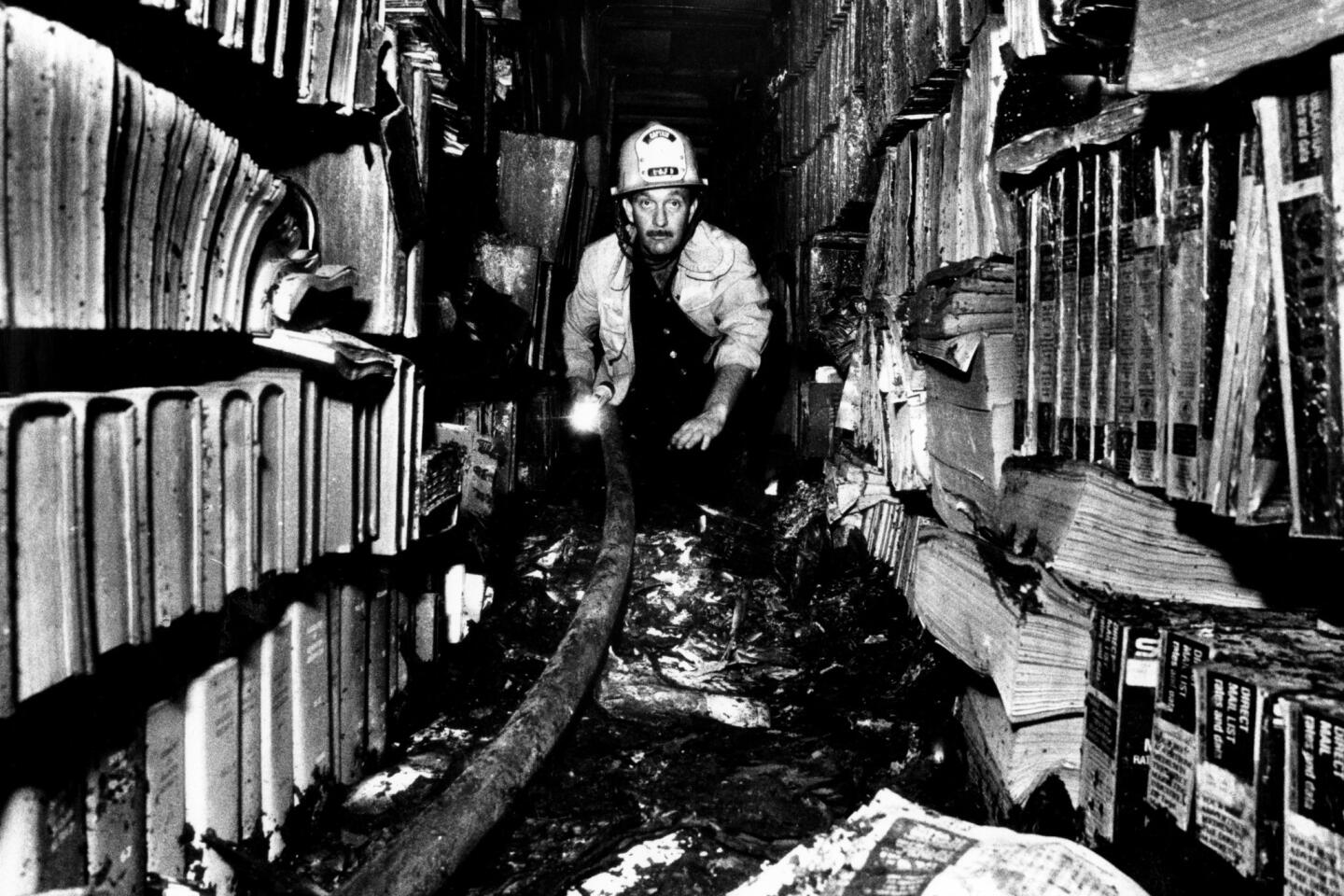

He seemed exasperated. “The big fire! The fire in 1986! It shut the library down for seven years!” As I later learned, the fire — an arson — consumed 400,000 books and damaged 700,000 more. It was the largest library fire in American history.

Now someone ought to do a book about that, I thought to myself, and I know it’s going to be me.

And so it was. I plunged into the story, learning everything I could about the fire, and about these beloved institutions. Over and over, I was reminded that we feel something really deep about libraries — they aren’t just warehouses of books, but instead represent a repository of everything we know and dream of and have explored. They seem to have souls.

While working, I came across an expression that intrigued me. In Senegal, when someone dies, it is expressed by saying his or her library has burned. I wasn’t quite sure what it meant, but I wrote it on a notecard and hung it over my desk, and I would read it every day that I was working.

When I was about halfway done with the book, my mom was diagnosed with dementia. Little by little, I understood that Senegalese expression, because her loss of memory and, eventually, of language, was like watching her interior life smolder and then disappear, as if consumed by fire.

When I finished the book, I realized that this entire time, I have been drawn to writing it, to writing in general, in hopes of creating something that endured, that would be alive somehow as long as someone read what I had written. This was my lifeline, my passion, my way to understand who I am and what I do. When I finally saw the book out in the world, I thought about my dad, and I knew, had he still been alive, that he might again be urging me to go to law school.

And I thought especially about my mother, who died before I finished it, and I knew how pleased she would have been to see me in the library, and that thought transported me to a split second to a time when I was young and she was still in the moment, alert and tender, with years ahead of her. I knew that if we had come to the library together, even now, she would have reminded me that if she could have chosen any profession in the world, she would have been a librarian.

That’s why I knew I had to write this book, to tell about a place I love that doesn’t belong to me, but feels like it is mine, like it belongs to all of us. All the things that are wrong in the world seem conquered by a library’s simple promise: Here I am, please tell me your story; here is my story, please listen.