I think we’re beyond peak fake news pandemic. The early fever of moral panic has abated. Attention is moving from symptoms to cause. And so begins the sober, purposeful work of rebuilding trust in the world’s information supplies.

That’s my hope after months of conversation with an inspirational coalition of journalists, technologists, researchers, and activists. At summits, hackathons and in working groups on both sides of the Atlantic, I’ve watched potential leaders emerge, conventional wisdoms challenged and enjoyed the dopamine rush of fresh thinking. And I’ve seen the ideals of this fledgling movement align with broader tectonic shifts in the media world.

Quality newsrooms have proudly reclaimed their ownership of facts and rallied record numbers of new subscribers. Tech leaders, advertisers, and democratic political elites have pledged support for the war on misinformation. Journalism, it seems, has become a global cause too important to be left to the journalists themselves.

Yet, the missionary zeal of this fledgling movement has been tempered by institutional inertia. A lively but circular conversation has produced only a vague framework of “jobs to be done.” A democratic dialogue is in danger of co-option by powerful interests who sense both danger and opportunity.

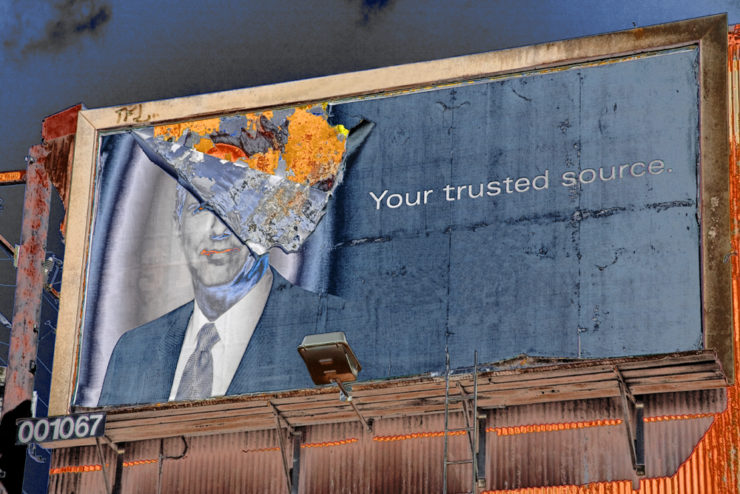

The war against misinformation poses a reputational and regulatory threat to big tech companies. News organizations sense a competitive opportunity to remind the world why they matter. Western political elites see a chance to stem the rising tide of populist rage. The war on disinformation is in danger of becoming a short-term marketing challenge for publishers, platforms, and policy makers.

If you were serious about restoring truth and trust to public discourse, you would not start here.

You would start with a recognition that the status quo is not working. The digital economy of news is bankrupt. Faith in journalism is critically undermined by an ad-based model of social distribution that rewards emotion over truth, reach rather than engagement. Short-term survival is inconsistent with long-term trust.

Let’s imagine the news business started from scratch. Assume that newsrooms no longer had to depend on broad appeal to a mass audience. The core metric of success for journalism was the value of the connection to the individual citizen. What would the digital economy of news look like if it was optimized for the trust of the end user?

Not too long ago, we used a retrofitted phrase knowledge economy to describe the positive impact of digital information networks. Let’s grab this proactive moment while it lasts and start mapping out a trust economy, in which the civic function of journalism is realigned with the needs of societies overwhelmed by too much information and too many choices.

The Distrust Economy

Before we imagine what a fresh start would look like, we need to consider the broader toxic shock of digital disruption in democratic societies.

The fake news crisis was never just about the supply of misinformation. It was about the demand for misinformation. Those who choose to focus solely on the primacy of facts have missed the underlying collapse of trust in journalism.

What would the digital economy of news look like if it was optimized for the trust of the end user?

The collapse of faith in journalism is part of a broader “implosion of trust” in public institutions. A loss of faith in trusted news sources reflects a rapid disintegration of consensus around previously self-evident values in society.

The foundations of social trust have been shaken by the clash of economics and psychology. Digital disruption has forced the human brain to adapt to an historic overabundance of information. But it also produced an economic model that penalizes trusted sources of information.

Every day, Americans consume five times more information than they did in 1986. There is simply no way the human brain has the capacity to process that historic surge, without falling back on the cognitive shortcuts that fuel our biases. “We face danger,” says Nate Silver, “whenever information growth outpaces our understanding of how to process it.”

The neural switchboard that manages our attention is fried. Anything that challenges our delicate grasp on equilibrium is unwelcome. Contradictory information triggers even greater loyalty to previously held belief.

That ominous new tagline for The Washington Post tells us “Democracy dies in darkness.” But democracy also dies when citizens turn away from the blinding light of competing facts.

The dispassionate voice of the journalist is often no match for the passionate voices that tell us we are right. Social media has allowed us to outsource our news supply to neighbors, friends, and family. Their recommendations are imbued with the feeling of authenticity that we crave.

When it comes to news consumption, not all social platforms are created equally. Facebook is by far the most potent news distribution channel in history. The enormous numbers who rely on its news feed have effectively outsourced part of their neural switchboard to Facebook engineers. The news may come from people we know, but it is ranked by an algorithm optimized for emotion and not truth. It feels true precisely because it makes us feel. Something. Anything.

The currency of this feed—and the programmatic ad marketplace it drives attention to—is emotion. For quality journalism to make it into the news feed, it must provoke some pre-determined reaction, and be priced accordingly.

The exhaustively reported investigation into the prison system gets dumped into the same advertising bucket as your top 10 celebrity detox diets. The only way to make real money in this system is to reach as many people as possible, by whatever means (or platform) necessary.

The very best and the very worst in journalism gets bundled together in one demoralizing scroll optimized for a laugh, cry, scream, and ultimately share. Journalism is no longer the solution to the information overload. It is just another source of distraction. Rather than relieving the burden on our brains, it adds to it.

If your goal was the catastrophic erosion of trust in journalism then you could not design a more effective model than this.

The News Feed Optimized for Trust

If you started journalism from scratch, you would no longer trade on a fleeting connection with the crowd. You would monetize the value of deep, meaningful connections to individuals.

The phrase “here comes everybody” defined the first democratic awakening of the digital age. “Here comes somebody” should be the words we live in the new trust economy.

In designing journalism for somebody, the first challenge is balancing the civic function of news with the monetized personal service that funds it. The strategy of connecting directly to individuals must serve the ultimate goal of reviving trust in public discourse.

Let’s go back to that original distinction between truth and trust. Journalism’s purpose is to safeguard the supply of objective facts around which citizens coalesce as a community. But all our hard work in preserving the sanctity of civic information is undone when journalism—at every other touch-point—makes the citizen feel like a commodity.

If journalists want somebody to care about the truth, they have to make somebody feel they have their back. “We trust people who have our interests at heart,” says Eli Pariser, the man who coined the phrase “filter bubble.” “We don’t trust people on the basis of their being correct factually.”

So, before asking how do we optimize news for trust, let’s make sure we understand how the user defines trust. Let’s ask ourselves why users seem to trust the social news feed more than the traditional newsroom it threatens to destroy.

News on my social feeds arrives as the shared experience of a friend or the benevolent recommendation of a family member. It is ranked by a hidden hand, but it feels like it was chosen for me, or the multiple versions of me that I choose to be.

My personality matters more than the demographic box you put me in. Whether I am open and extrovert, conscientious and neurotic, is often more important than whether I am an 18-34 urban female.

The hidden hand of the Facebook news feed betrays the original democratic promise of social media

I have multiple identities at any given moment. I expect my news feed to reflect my needs as a parent, driver, taxpayer, neighbor, saver, and volleyball fanatic. I have passions that are simultaneously global and tribal. I like cake. And broccoli.

Social platforms and marketers understand the complex web of affinities that define somebody. That’s how they built a news feed that you “feel” can be trusted. News organizations must understand the dark arts of psychometrics and data mining in order to build a version of this news feed, but one that is better, one that is actually worthy of trust.

The organizing principle of the news feed of trust is that somebody wants less choice as long as it delivers more utility. Remember, information overload has fried their neural switchboard. They need a friend to help manage their attention, not tax it.

Somebody no longer expects a single news brand to offer a little taste of everything. This news feed will reward sources with a deep understanding of a user’s interests and an ability to take care of them.

The news feed of trust would be a stark counterpoint to the never ending, demoralizing scroll of sad, happy, and angry. It would represent a return to lost sense of completion. My bet is that if you can help somebody feel they have “finished the internet” on any given topic on a given day, they will invite you back tomorrow.

The hidden hand of the Facebook news feed betrays the original democratic promise of social media. I was first captivated by Twitter as a TV anchor because it enabled a two-way conversation with a formerly passive audience. I didn’t have all the answers, not even all the questions. Somebody did. Our bond was equality, openness, curiosity, but never authority (ultimately, I would create a start-up newsroom based on my experience of this “human algorithm”).

Journalists and citizens are anesthetized by the passive, inert roles we are forced to play by a broken system. The news feed of trust would restore a two-way dialogue of equals, in which the user is not constantly reminded they are the commodity.

Imagine the interaction between a journalist and somebody that was free from advertising. Ads are blocked so the article loads faster. There are no videos to be skipped. No puzzling reminders of past purchases. No clickbait widgets dragging you from journalism as a personal service to journalism as manufactured distraction.

This is the killer app of the trust economy.

Attention Must Be Paid

If advertising is not paying for the news feed of trust, then it will require a direct transaction between user and the journalist (or someone collecting the cash on behalf of the journalist). The question is will somebody pay in the right quantities to deliver journalism from the clutches of distraction?

Momentum is clearly on our side. Quality news organizations across the world have been enjoying a spike in paid subscriptions (and there are signs this is more than simply a Trumpian cry for help).

Yet, even if this shift continues, our current frame for paid news is no longer fit for purpose. Expecting users to agree to fixed-term payment plans to multiple news organizations in order to curate a daily news feed … ? We will look back on this with bemusement, just as we remember a time when a passive audience had no choice but to tune in at 9 o’clock for the news.

This silo mentality is one of the reasons I can’t see the world’s largest news organizations, or dominant technology platforms, delivering the kind of collaborative infrastructure we need for our trust economy.

Platforms and publishers may appear to come from different planets but they are both fundamentally introspective. Their cultures are self-referential and closed, grounded in insider jargon and intellectual uniformity.

Some of the most talented media innovators work for legacy publishing groups. But, by definition, their immediate focus has to be the survival of their brand, in this moment of crisis.

The big platforms didn’t set out to be the news empires. They now face ethical dilemmas that do not compute. I mean that literally. A problem is not a problem unless it has a product team, an OKR, and potential to scale.

Our trust economy will not emerge from institutional cultures as long as they only attach significance to what can currently be measured or priced. So, if the conversation about the future of journalism were taken out of the institutional construct that defines it, what would it sound like?

The Architects of Trust

On my travels in recent months, I’ve been listening to an emerging network of trust architects: first-time entrepreneurs, seasoned innovators, civic activists, venture capitalists, tech-minded journalists, and news-junkie technologists.

Some are collaborating around the challenges of misinformation. Others are working independently (and often below the radar) on the various infrastructural challenges of rebuilding trust.

What unites the trust architects—whether they are conscious of it or not—is their common focus on economic incentives that directly align journalism with the needs of the user.

Some advocate a swift, transformational break-up between advertising and journalism. One of the light-bulb meetings on my recent travels was with Tristan Harris, former Google designer and founder of Time Well Spent, who has exposed the bankruptcy of the attention economy with uncommon clarity. Others focus on disrupting rather than destroying ad-based models, or like the Sleeping Giants group, starving misinformation merchants of ad revenue.

Either way, the bedrock of the trust economy is somebody paying directly for journalism. And this is where some of the most promising trust architects are at work. Between the current blunt instrument of individual subscription plans, and the problematic nirvana of a Netflix for news, are active experiments in micropayments, tipping, and crowdfunding. Among those building the “wallet” of the trust economy are established start-ups like Blendle, and rising stars like PennyPass, Scroll, Discors, and LaterPay.

“Here comes somebody” should be the words we live in the new trust economy

An early discovery of the trust architects is that the act of paying for journalism changes the nature of how journalism is packaged. The news feed optimized for trust will be a collection of journalism, personally curated for—or perhaps by—somebody. As a power user, I program my personal news feed through apps like Nuzzel and Pocket. I’m fairly sure these are the prototypes for the broad adoption of personal curation in our trust economy.

Journalism for somebody will require an ever-expanding supply of content tailored to multiple personalities and tribes. The increasing role of artificial intelligence in content creation is a huge potential benefit to a trust economy, as long as it remains very clearly within the service of human connection. The success of a platform like Patreon points to the rising importance of the personal media brand who serves a “passion” rather than a “vertical.”

The trust economy will involve profound changes in the culture of the newsroom. Like so many others, I’m a fan of the work of Dutch start-up, De Correspondent (and its new “ambassador” Jay Rosen) which has provided something close to a mission statement for the trust architect.

“We promised our readers that we’d help them understand the world around them better. That’s what they signed up for. Not saving our jobs.”

Existing news publishers have to worry about saving jobs. They are still prisoners to a business model not of their choosing. As for the platforms, as long as journalism is not core to their mission, they will face their own “innovator’s dilemma.”

I firmly believe the trust economy will be shaped by all the instincts and energy that defines the entrepreneur. But it will be a different type of entrepreneur than the one we lionize on stage at industry conferences.

My guess is that the next billion-dollar innovation in media will not come from a single company holding sway over a huge audience. It will emerge from an ecosystem of innovators doing the unglamorous, purposeful work on building foundations, paving roads, and laying the pipes for journalism somebody can trust.

That’s a movement I’d be very proud to be a part of.