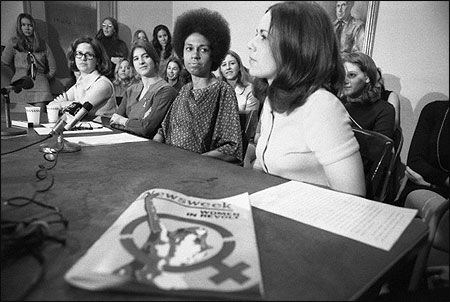

In March 1970, women employees of Newsweek, angered at being barred from reporting and writing jobs, sued the magazine for sex discrimination. It was the week the women’s movement was the cover story. Eleanor Holmes Norton, second from right, was their attorney. Photo © Bettman/Corbis.

During its civil war, tiny El Salvador was a place where correspondents could go out to rural battle sites and guerrilla camps during the day and return to the capital in time for dinner in a good restaurant. On one such evening in 1982, about a dozen of us enjoyed a roast-pig feast and fine wine as guests of the late Abe Rosenthal, executive editor of The New York Times. As we ate, a television correspondent asked Abe how our experiences in Central America compared with his covering the war in breakaway Katanga province in the Congo two decades earlier.

"The most obvious difference," Abe responded, "is that here I am surrounded by women."

While that may have been a slight exaggeration, there were women at the table representing the Times, The Washington Post, Newsweek, The Miami Herald, and probably others.

Looking back, I can see that an incredible change had occurred in opportunities for women in the relatively short time since 1970, when women at Newsweek sued to stop sex discrimination at the newsmagazine. Their battle was not about slogging along muddy roads and pursuing recalcitrant army officers but about gathering the courage to say, "Enough!" to the mainly Ivy League gentlemen with whom they worked side by side. They shared food, drink, good times, late nights at the office when the magazine closed, and, yes, beds—but not the titles, glory, promotions and raises.

Lynn Povich, who began her career at Newsweek as a secretary and news aide in the Paris bureau after graduating from Vassar in 1965, recounts all of this in "The Good Girls Revolt: How the Women of Newsweek Sued Their Bosses and Changed the Workplace." It's not a sweeping book about women's rights on the job or even about women and journalism, but a sort of genteel tell-all and intimate description of how one group of women faced the expanding horizon that the 1960s brought. Some were determined; some were reluctant. It's a highly readable account laden with names most of us recognize, often in unflattering circumstances.

However, as the product of the land of Amelia Earhart and Carrie Nation and of state universities where I never feared to raise my hand, I can't help but see the Newsweek women as timid and quaint, even for their time. It was my time, too. By the '60s, doors were opening for women (and minorities), and women who wanted real journalism jobs didn't go into a female ghetto called the research department at Newsweek. The late Nora Ephron, who left Newsweek for the grittier world of the New York Post, told Povich years later: "I knew I was going to be a writer, and if they weren't going to make me one, I was going to a place that would."

Povich herself, even though she went on to a successful career both in and out of Newsweek, wonders "why the rest of us didn't get it, why we just didn't leave and try our luck elsewhere. Maybe because we were simply happy to have jobs in a comfortable, civilized workplace that dealt with the important issues of the day."

This book is revealing of the sense of entitlement and anointment felt by these women who came mostly from elite women's schools—where they "could be the first to raise their hands"—and thought it was their right to stay in the cozy white-shoe world surrounded by men from similar backgrounds. Most of them seemed to be grappling with whether to give up their pillboxes and the rest of the Jackie Kennedy mystique.

Trish Reilly, one of the women who sued, later found herself too conflicted about her life and ambitions to accept a transfer to the Los Angeles bureau, a step toward advancement. She told Povich: "I just didn't think girls should behave like that—take a man's job. I found it a little improper."

Indeed, many of the Newsweek women probably found inspiration in the path taken by a reporter in the arts section, who went to interview lyricist Alan Jay Lerner and wound up as the fifth of his eight wives. "For many of us, Newsweek was just a way to earn pin money before getting hitched," Povich acknowledges.

Change At The AP

Three years after the Newsweek women filed their suit, I put my name at the top of a class action complaint against The Associated Press. I was a correspondent in the AP's United Nations bureau and had worked as an editor and writer on the foreign and world desks at AP headquarters in Rockefeller Center. Those desks were traditional paths to foreign assignments for the overwhelmingly male AP news staff.

When I arrived in New York at the end of 1968 after a year of post-graduate research in Chile, the foreign editor declared that a woman would go abroad over his dead or retired body. During the coming five years I sat by as my male contemporaries, after a year or two on one of the desks, were dispatched into the wide world. Many of them were sympathetic to my dreams and saw the unfairness in my regularly being passed over. Several wondered why I didn't sue; one offered to set up a meeting with a lawyer friend.

Unlike Newsweek, the AP did not have a female ghetto; it simply had very few women. I felt alone and certain of immediate reprisal if I mounted a legal challenge. Then the Wire Service Guild stepped forward to organize a group of lead plaintiffs and to underwrite expenses.

Ours was a long and winding road to settlement 10 years later, but in a reflection of the rapidly changing times, and perhaps the suits by the Newsweek and Times women and others, things began to change almost as soon as our complaint was filed in October 1973. The executive ranks of the AP went through a generational change; those who had covered D-Day retired.

By the time we settled in 1983, women had increased to 22 percent of the domestic news staff, up from 7 percent in 1973, and those in foreign assignments had grown proportionately. All of the named plaintiffs had departed for other jobs, and I had been graciously congratulated in a New York courtroom by one of the AP's mega-priced attorneys for winning the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for The Miami Herald.

Still, ours was a settlement of breathtaking scope that covered both women and blacks, including $2 million for back pay and various training and incentive programs. More importantly, it set ambitious goals for continuing growth in female and minority hiring and promotion. Today, I see the results every time I open the quarterly AP house organ filled with articles about hiring, promotions, news coverage, and the people at the very top.

All of us who were involved in these battles had to overcome our individual fears and hesitations, but the times called for us to do just that. Eleanor Holmes Norton, the first attorney for the Newsweek women, explained: "I grew up black and female at the moment in time in America when barriers would fall if you'd push them. I pushed … and then just walked on through."

Some of the Newsweek women had trouble walking through the doors once opened, but all of them deserve praise for daring to push.

Shirley Christian, a 1974 Nieman Fellow, is the author most recently of "Before Lewis and Clark: The Story of the Chouteaus, the French Dynasty that Ruled America's Frontier," published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in 2004.