The vast majority of journalists covering the war in Iraq—well more than 500 of them—chose to do so through participating in the U.S. Department of Defense’s embedding program. This was the most comprehensive effort to date by the American military to show journalists its operations by including them at every stage, from preparation for battle to the war. By contrast, relatively few stayed in Baghdad or entered the country on their own.

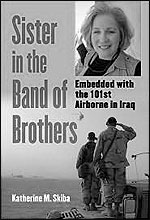

In her book, “Sister in the Band of Brothers,” Katherine M. Skiba, who was an embedded correspondent for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, describes the program as generally working well. In most places journalists, Skiba included, obtained unprecedented access to military operations. It was not easy to do so, and she observes that journalists often had to wrestle with two mistaken and conflicting assumptions on the part of military officials: that the journalists, as fellow Americans, were on the soldiers’ side and sympathetic to them or, alternatively, that the journalists were the enemy trying to disgrace the soldiers in the media.

Portraying the Embedded Experience

However, as Skiba’s book shows, the greatest problem that confronts embedded reporters and their editors is that the journalist’s view of the war is limited. Skiba describes her inability to see much beyond what was happening in her unit and acknowledges she had little sense of the overall prosecution of the war. Nor does she have a sense of the impact the war is having on the “enemy.” She also has little access to the kind of information that might shed light on military decision-making. Indeed, Skiba makes no grand claims about the scope of her reporting role and describes her coverage as giving a “‘keyhole’ view of the war—richer, deeper, three dimensional, and colorful, but infinitely narrower, never much beyond the activities of the 2,300 strong 159th Brigade.”

Hers is a modest book that makes no pretense of telling the complete story. But for readers interested in understanding how embedding works—its opportunities and limitations—her depiction offers a close-up look. She was able to do what the rank-and-file foot soldier doesn’t have time to do: write down what life is like day-to-day in the midst of battle.

The most compelling aspect of her book is her vivid, “you are there” description of life with the 159th Aviation Brigade, a helicopter unit within the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army. She describes the initial stages of a sandstorm that threatened to maroon the bus on which she is traveling; the soldiers rip apart boxes used for readymade meals to fortify the ceiling hatches and the rear emergency door where the sand is seeping in. Later, when the unit with which she is embedded is barely nine miles from the Iraqi border, it comes under a missile attack. A soldier shouts “Gas, gas, gas.” Suddenly we are there with Skiba as she anxiously tries to put on the gas mask, can’t get the elastic bands to work properly, and then runs for the foxholes with the other soldiers. After several more putative missile attacks through the next evening, Skiba’s words allow us to share the soldiers’ exhaustion at having to rouse themselves time after time to put on their gas masks and run for cover.

Skiba’s book is also about the bonds that form between embedded reporter and soldier. Although Skiba does not explore the consequences much, it is clear that skepticism and objectivity are casualties of the embedding experience to greater and lesser degrees. She is honest about the longing for companionship and the loneliness of being in the midst of a battlefield as an outsider and, therefore, the need to find kindred spirits with whom to talk about the experience. When sharing a life and death experience—such as the risk of being under attack from chemical weapons—the journalist is closer to being one of the soldiers than to being a detached observer.

Skiba is a careful observer; she describes the military with an outsider’s eye and a reporter’s attention to detail. As a female correspondent, she brings an added sense of herself as being separate from those she is covering. The vast majority of those operating in war zones are men—whether in the military or the correspondent corps. As I have also learned covering the war in Iraq, to be a woman is both an advantage and a disadvantage. You are not party—for the most part— to the “one of the boys” jokes or their shorthand comments. But there is a presumption that you, as a woman, will be empathetic. In the eyes of one soldier, you become a daughter; to another, a sister, and through the eyes of yet another, a wife and confidante.

These associations mean that some soldiers respond in a different way than they would with male reporters, and some of the best bits of Skiba’s book are snatches of conversation in which young men describe loneliness, fear and frustration, or show off their prowess with weapons. She quotes Private 1st Class Chad Weins, a 22 year old from St. James, Minnesota, shortly after the war has begun, saying that it was good because “We need to get Saddam out of power.” But as she describes the way he says what he says, Skiba notes that, “he punctuates almost every sentence with a nervous ‘I guess.’”

T he View From the Trenches Her observation of the young private’s uncertainty speaks volumes about the day-to-day sense most soldiers have of being cogs in a wheel. But this view from the trenches is a story we know pretty well by now. Since the Civil War, journalists have been able to travel with the troops, and many books have been written out of those experiences, including Michael Herr’s “Dispatches” about the war in Vietnam.

The remarkable change in coverage that occurred during and after the invasion of Iraq had little to do with the U.S. military’s embedding program. Rather, for the first time journalists had unprecedented access to the theater of war both during and after the invasion itself. From Kuwait, unilateral journalists followed the U.S.-led coalition of troops into Iraq, and as soon as the statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down in Firdos Square, Western journalists were roaming Baghdad’s neighborhoods, their movements restricted, if at all, only by their own aversion to risk. Most past wars involving American troops have offered few, if any, of these kinds of reporting opportunities. For example, the U.S. press corps did not interact with the North Vietnamese or the North Koreans. In recent wars, the press has had similar access only in the Balkans. In Bosnia and to a lesser degree Kosovo, reporters could talk to people on all sides, but in those situations the U. S. role was less prominent, and it was not operating as an invading force.

Iraq, by contrast, has been open ground for journalists. For the first time it has been possible for large numbers of journalists to observe closely the behavior of U.S. troops and how it refracted among Iraqis. When U.S. troops opened fire on speeding cars and killed civilians or raided neighborhood homes, journalists were not limited to reporting the military’s own account but could get to the scene and interview eyewitnesses. Such reporting presented its own set of problems, since it was not uncommon to encounter conflicting “eyewitness accounts” and to find out that some were completely fabricated. Those of us trying to verify the basic facts of these shootings—and listening to the ways in which Iraqis described them—came away with considerable insight into the nature of war including the resentment the U.S. military presence was increasingly reaping.

These widespread sentiments of resentment among Iraqis and their sense of being treated as “the enemy,” even when they had not done anything, have fed the nascent insurgency. By the summer of 2003, a few months after the invasion, it was clear that one of the key aspects of the ongoing violence in the country was the disjunction between Iraqis’ perception of the American military’s behavior and the U.S. military’s own view. While it is certainly important to know how the soldiers perceived and experienced the battlefield—and Skiba’s reporting provides a close-up picture of the 159th Brigade’s world—this is only one part of the larger mosaic. And from a public policy perspective, it is hardly the most important piece since the key questions remain: Why are we in Iraq? And what have we accomplished?

Alissa J. Rubin was the Baghdad co-bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times until February 2005. She is now the Vienna bureau chief, although she still covers Iraq periodically. Prior to going to Iraq in 2003, Rubin reported from the Balkans, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In her book, “Sister in the Band of Brothers,” Katherine M. Skiba, who was an embedded correspondent for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, describes the program as generally working well. In most places journalists, Skiba included, obtained unprecedented access to military operations. It was not easy to do so, and she observes that journalists often had to wrestle with two mistaken and conflicting assumptions on the part of military officials: that the journalists, as fellow Americans, were on the soldiers’ side and sympathetic to them or, alternatively, that the journalists were the enemy trying to disgrace the soldiers in the media.

Portraying the Embedded Experience

However, as Skiba’s book shows, the greatest problem that confronts embedded reporters and their editors is that the journalist’s view of the war is limited. Skiba describes her inability to see much beyond what was happening in her unit and acknowledges she had little sense of the overall prosecution of the war. Nor does she have a sense of the impact the war is having on the “enemy.” She also has little access to the kind of information that might shed light on military decision-making. Indeed, Skiba makes no grand claims about the scope of her reporting role and describes her coverage as giving a “‘keyhole’ view of the war—richer, deeper, three dimensional, and colorful, but infinitely narrower, never much beyond the activities of the 2,300 strong 159th Brigade.”

Hers is a modest book that makes no pretense of telling the complete story. But for readers interested in understanding how embedding works—its opportunities and limitations—her depiction offers a close-up look. She was able to do what the rank-and-file foot soldier doesn’t have time to do: write down what life is like day-to-day in the midst of battle.

The most compelling aspect of her book is her vivid, “you are there” description of life with the 159th Aviation Brigade, a helicopter unit within the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army. She describes the initial stages of a sandstorm that threatened to maroon the bus on which she is traveling; the soldiers rip apart boxes used for readymade meals to fortify the ceiling hatches and the rear emergency door where the sand is seeping in. Later, when the unit with which she is embedded is barely nine miles from the Iraqi border, it comes under a missile attack. A soldier shouts “Gas, gas, gas.” Suddenly we are there with Skiba as she anxiously tries to put on the gas mask, can’t get the elastic bands to work properly, and then runs for the foxholes with the other soldiers. After several more putative missile attacks through the next evening, Skiba’s words allow us to share the soldiers’ exhaustion at having to rouse themselves time after time to put on their gas masks and run for cover.

Skiba’s book is also about the bonds that form between embedded reporter and soldier. Although Skiba does not explore the consequences much, it is clear that skepticism and objectivity are casualties of the embedding experience to greater and lesser degrees. She is honest about the longing for companionship and the loneliness of being in the midst of a battlefield as an outsider and, therefore, the need to find kindred spirits with whom to talk about the experience. When sharing a life and death experience—such as the risk of being under attack from chemical weapons—the journalist is closer to being one of the soldiers than to being a detached observer.

Skiba is a careful observer; she describes the military with an outsider’s eye and a reporter’s attention to detail. As a female correspondent, she brings an added sense of herself as being separate from those she is covering. The vast majority of those operating in war zones are men—whether in the military or the correspondent corps. As I have also learned covering the war in Iraq, to be a woman is both an advantage and a disadvantage. You are not party—for the most part— to the “one of the boys” jokes or their shorthand comments. But there is a presumption that you, as a woman, will be empathetic. In the eyes of one soldier, you become a daughter; to another, a sister, and through the eyes of yet another, a wife and confidante.

These associations mean that some soldiers respond in a different way than they would with male reporters, and some of the best bits of Skiba’s book are snatches of conversation in which young men describe loneliness, fear and frustration, or show off their prowess with weapons. She quotes Private 1st Class Chad Weins, a 22 year old from St. James, Minnesota, shortly after the war has begun, saying that it was good because “We need to get Saddam out of power.” But as she describes the way he says what he says, Skiba notes that, “he punctuates almost every sentence with a nervous ‘I guess.’”

T he View From the Trenches Her observation of the young private’s uncertainty speaks volumes about the day-to-day sense most soldiers have of being cogs in a wheel. But this view from the trenches is a story we know pretty well by now. Since the Civil War, journalists have been able to travel with the troops, and many books have been written out of those experiences, including Michael Herr’s “Dispatches” about the war in Vietnam.

The remarkable change in coverage that occurred during and after the invasion of Iraq had little to do with the U.S. military’s embedding program. Rather, for the first time journalists had unprecedented access to the theater of war both during and after the invasion itself. From Kuwait, unilateral journalists followed the U.S.-led coalition of troops into Iraq, and as soon as the statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down in Firdos Square, Western journalists were roaming Baghdad’s neighborhoods, their movements restricted, if at all, only by their own aversion to risk. Most past wars involving American troops have offered few, if any, of these kinds of reporting opportunities. For example, the U.S. press corps did not interact with the North Vietnamese or the North Koreans. In recent wars, the press has had similar access only in the Balkans. In Bosnia and to a lesser degree Kosovo, reporters could talk to people on all sides, but in those situations the U. S. role was less prominent, and it was not operating as an invading force.

Iraq, by contrast, has been open ground for journalists. For the first time it has been possible for large numbers of journalists to observe closely the behavior of U.S. troops and how it refracted among Iraqis. When U.S. troops opened fire on speeding cars and killed civilians or raided neighborhood homes, journalists were not limited to reporting the military’s own account but could get to the scene and interview eyewitnesses. Such reporting presented its own set of problems, since it was not uncommon to encounter conflicting “eyewitness accounts” and to find out that some were completely fabricated. Those of us trying to verify the basic facts of these shootings—and listening to the ways in which Iraqis described them—came away with considerable insight into the nature of war including the resentment the U.S. military presence was increasingly reaping.

These widespread sentiments of resentment among Iraqis and their sense of being treated as “the enemy,” even when they had not done anything, have fed the nascent insurgency. By the summer of 2003, a few months after the invasion, it was clear that one of the key aspects of the ongoing violence in the country was the disjunction between Iraqis’ perception of the American military’s behavior and the U.S. military’s own view. While it is certainly important to know how the soldiers perceived and experienced the battlefield—and Skiba’s reporting provides a close-up picture of the 159th Brigade’s world—this is only one part of the larger mosaic. And from a public policy perspective, it is hardly the most important piece since the key questions remain: Why are we in Iraq? And what have we accomplished?

Alissa J. Rubin was the Baghdad co-bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times until February 2005. She is now the Vienna bureau chief, although she still covers Iraq periodically. Prior to going to Iraq in 2003, Rubin reported from the Balkans, Afghanistan and Pakistan.