“Can star player Marco Fabián revive the Union’s Latino fan base? Show me some cariño (affection), they say.”

That was the headline for an April 2019 Spanish-language multimedia feature in The Philadelphia Inquirer about Mexican soccer player Marco Fabián, star of the Philadelphia Union team, which over the previous nine years had dropped most of its Hispanic players.

In the piece, Inquirer staffer Jesenia De Moya Correa unpacks, through interviews with several Spanish-speaking sources of different ages and nationalities, what having a Mexican player on the Philadelphia squad means to the city’s Latinx communities. It wasn’t the first time the Inquirer had covered Fabián or the local league. However, it was the first time that the story was told through voices from the community.

“To have a reporter there among them, chatting and debating about the future of the league, was really moving for them,” De Moya says of her interviews. Through the article, Philly’s Latinx communities were able to see themselves reflected in the local news, which they could read in the language of their choice.

For Latinx news consumers, that’s been an all too rare experience — and one that a growing number of independent outlets are determined to change.

There are over 60 million Latinxs in the United States, comprising 18.5% of the population. (Latinx is a panethnic label that embraces the fluidity of these communities, which is why the term is used in this piece.) While many Latinxs share a language, religion, and many aspects of culture, the group is not monolithic. Yet news outlets have often been blind to this diversity, most notably during last November’s presidential election when many anchors, analysts, and commentators were shocked to learn that large percentages of Latinxs in Texas and Florida had supported Donald Trump.

While many Latinxs share a language, religion, and many aspects of culture, the group is not monolithic. Yet news outlets have often been blind to this diversity

“The main problem with mainstream media is that they’ve always imagined that they served everyone when they actually served an audience that was mainly white, middle-class, and with a certain level of education,” says Graciela Mochkofsky, director of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism’s Spanish-language program and the Center for Community Media at CUNY, who has long emphasized the importance of Latinx representation in the media. “There has only been one community that has been fully represented or served by these outlets, who were under the fantasy that they were serving everyone.” Mochkofsky points out, for example, that Spanish-media newsrooms tend to focus on an older generation of Latinxs, when the second- and third-generation experience — the experience of the children and grandchildren of first-generation immigrants who may not even speak Spanish — is just as important.

There is a growing ecosystem of newsrooms serving these audiences. Futuro Media Group, an independent nonprofit producing multimedia journalism; “Radio Ambulante,” a Spanish-language podcast; Remezcla, which brings visibility to Latinx culture; palabra., an NAHJ initiative that covers stories of communities that have been disregarded; and Puerto Rico-based Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, with investigative journalism at its core.

Joining these more established outlets is a cohort of newsrooms exploring how the current polarized political climate and the tragedies that have unfolded over the past four years — from Hurricane Maria to the El Paso shooting to the Covid-19 pandemic — are impacting Latinx communities.

EL INQUIRER

At the Inquirer, De Moya Correa had been hired to develop a content strategy to reach the city’s large Spanish-speaking population. Her piece on Marco Fabián was the first of her work to be published in Spanish, and it was a catalyst for the founding of El Inquirer, a repository for Spanish-language coverage and translations of Inquirer stories of relevance to Latinx readers.

Historically, the Inquirer’s relationship with the city’s Latinx communities has been rocky. With a newsroom that is 74% white, the Inquirer dedicated only 3.4% of its coverage to Latinx communities, the fastest-growing demographic in the United States after Asian-Americans. In Philadelphia, the Latinx population nearly doubled between 2000 and 2018, from 8.5% to 14.5%. Puerto Ricans or people of Puerto Rican origin are the largest group, but Philadelphia is also home to a large number of Mexicans, Dominicans, Cubans, and Venezuelans, among other Latin American groups.

De Moya’s job was to improve the Inquirer’s coverage of and relationship with Latinx communities. The problem, however, was that there was no relationship with them to begin with.

“The environment was incredibly hostile,” says De Moya, who was born in New York to Dominican immigrants. Reporting in the field, potential sources would ask her, “Who are you working for?” When she replied she was with The Philadelphia Inquirer, people ignored her or even asked her to leave their streets. “You only come here to report on crime or scandal,” De Moya says a block organizer once told her.

De Moya has persisted, though, sending emails and WhatsApp messages to community leaders, people from religious institutions, council members, activists, and teachers who could guide her to the topics the Inquirer needed to cover. That effort is starting to pay off, with El Inquirer slowly getting the support of members of the Latinx communities.

“The newspaper is finally giving validation to these communities in their own language,” says De Moya. “However, it’s been up to us to build somewhat of a communication strategy so people can find out about our work.” The next step for the paper is to do original reporting specifically for El Inquirer and develop coverage strategies for the entire newsroom.

EMPERIFOLLÁ

Emperifollá is an outlet that since its founding in 2019 has covered the influence of Afro and Indigenous communities on culture, fashion, and beauty, Andean culture in fashion, and the lack of Black Latinx representation in the media.

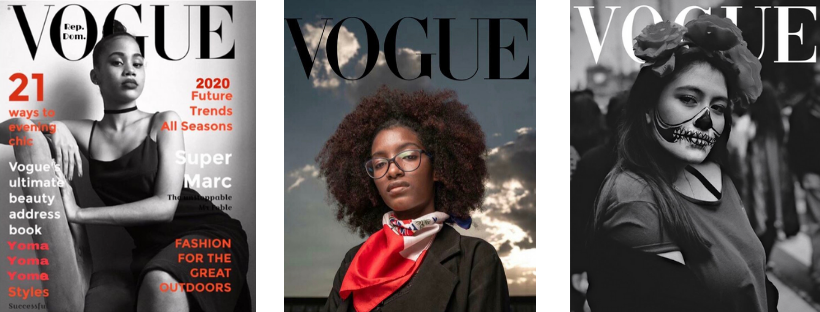

In “This Is What Latinx Media Could Actually Look Like,” Puerto Rican founder Frances Solá-Santiago tackles the “#VogueChallenge,” a social media initiative that invited users to post their own versions of a Vogue cover. “More than a creative challenge, it’s a chance to highlight Black, Indigenous, Asian, Latinx, and other races and ethnicities around the world who’ve been historically overlooked by fashion and beauty magazines,” she wrote.

The piece speaks to the reckoning over diversity in fashion while emphasizing that media employees from racialized communities have often been overlooked and mistreated, as evidenced by the spate of resignations during the summer of 2020 of top editors from outlets like Bon Appetit, Refinery29, and The Philadelphia Inquirer over racist behaviors and discrimination against employees of color. The lack of diversity “has influence over Latinx communities and media,” says Solá-Santiago. “This affects marginalized groups and reinforces Eurocentric beauty standards. At Emperifollá, our premise is that fashion and beauty are inherently political. It’s our responsibility to look into the nuances of the communities we aim to represent and serve.”

To be emperifollá or emperifollada means to be well dressed and groomed, to look decorated. The term is popularly used across Latin America but resonates deeply in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic. Solá-Santiago got the idea for the site after reading “The Joy of Always Being Emperifollá,” a 2018 personal essay by Laia Garcia-Furtado that explores the author’s relationship with fashion and the women who raised her.

Solá-Santiago was reminded of her grandmother, mother, and aunts putting on their powder and lipstick, always looking emperifollá as a way of highlighting their presence and power. She started a Twitter thread to explore what other people had to say about emperifollá. The result was a site to cater to a Latinx millennial audience.

The first issue, in March 2019, “At Abuela’s House,” analyzed different elements of many Latinx Millennials’ grandmothers’ houses and the experiences around it: red lipstick, hot coffee, Maria biscuits, dominoes, and hand mirrors — an ode to their culture and the women who raised them. “We were taking the collective imagery of our upbringing to question what it says about us,” says Solá-Santiago. “This was something very different from other Latinx fashion and beauty coverage that tends to be centered around stereotypes such as the ‘spicy Latinas.’ My generation is more about self-expression and gender fluidity. We understand that a Latina is not necessarily a curvy heterosexual woman.”

“At Abuela’s House” features drag queen Vena Cava, the stage name for Puerto Rican creative Anthony Velázquez, and Afro-Latina model Anastasia Lovera wearing abuela-like clothing by Latinx designers: polka dots, golden earrings and rings, saint medallions, and shiny tunics. The goal: to juxtapose old-school behaviors with a new inclusive moment. “It was a reflection of our own experiences, remembering the afternoons we spent at our grandmother’s house,” says Solá-Santiago. “This house celebrates racial diversity and gender fluidity, which is why we picked those models. The audience perceived this straight away and saw themselves reflected in the pictures and the story they told.”

Six months after launch, Emperifollá began getting invitations to participate in events and panels, reaching a predominantly female English-speaking audience aged between 18 and 35. At the moment, close to 7,000 viewers consume Emperifollá’s content every month. In September 2019, O, The Oprah Magazine featured it as one of the 10 Latina-owned businesses to support. Two years into the project, Solá-Santiago and her team have been able to make money through branded partnerships, grants, and a Patreon platform.

EL TÍMPANO

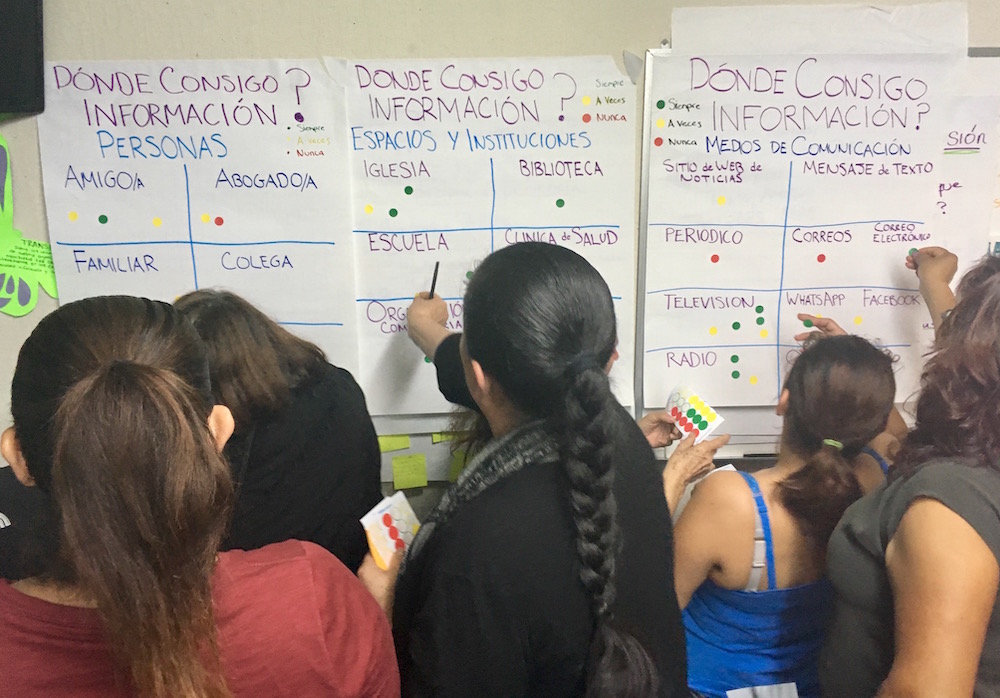

For the past two years El Tímpano, a Spanish-language text-messaging service and reporting lab in Oakland, California, has delivered news by creating a loop between journalists and their Spanish-speaking audiences. Residents share their problems and concerns with journalists; journalists share their findings through an SMS platform. The community dictates the kind of news it needs and offers feedback on that content.

Founder and Oakland native Madeleine Bair noticed a crucial aspect that was missing in the city’s local media when she returned to her hometown in 2017: Latinx voices. “This year has been primarily focused on Covid because our audience has been the most impacted by it,” she says. “The most relevant information, such as renter protection or where to get tested, isn’t always available in Spanish on the channels and tools that they use.”

For instance, El Tímpano sent out a message asking how Covid-19 has affected people’s personal finances. Among the many responses was one from a man who had lost his job due to the pandemic and didn’t qualify for government aid. He asked how he could access financial help to pay his rent, and El Tímpano answered his question, providing him with the resources he needed. El Tímpano is responsive to user feedback, too. When a woman mentioned that El Tímpano always referred people to numbers that often don’t pick up, the outlet started providing other resources that were more easily accessible.

Bair, who is fluent in Spanish, grounded her startup in extensive research. She reached out to community leaders — church pastors, educators, advocates, people who worked with Oakland’s Latinx immigrant communities — and held workshops as well as surveying some 300 residents. “Latinos are the largest growing group in the city, and yet if you didn’t live or work in East Oakland, you had no way of knowing this because the voices and narratives of Latino immigrants are nearly invisible in local media,” says Bair. People of Latinx or Hispanic origin make up 26.5% of Oakland’s population. Spanish is the most common non-English language, spoken by 21.8% of the population.

Bair found that most people were either getting their news from Univision and Telemundo, the major Spanish-language media outlets, or local radio stations that covered the entire Bay Area. She also found that many residents were getting information from grassroots organizations, provided during meetings, while many others avoided the news altogether. Bair says many felt the news only painted them as victims or covered their communities when something bad happened: “This doesn’t mean they want feel-good news, but news that can help them take action.”

With funding from California Humanities, El Tímpano collaborated with local artist Ivan López to create a microphone sculpture. It was set up in different neighborhoods throughout East Oakland, and street vendors, construction workers, newly arrived immigrants, and other residents were invited to share stories about the rise in rents and other housing issues. In alliance with El Tecolote, an advocacy journalism newspaper in San Francisco, El Tímpano published some of these stories, in which people talked about being forced to move due to eviction, living in extremely poor sanitary conditions, and the increasing crime rate in their neighborhoods.

Since last spring, the pandemic has been the most crucial issue affecting the communities El Tímpano serves. Most recently, the team collaborated with The Oaklandside to report on how the local public health system is too overwhelmed to follow up with sick residents, a topic that came from audience questions.

“It’s important to note that as El Tímpano has developed a relationship of trust and reciprocity with our SMS community, community members are increasingly sending questions to us that are not directly in response to the messages we send out,” says Bair.

El Tímpano has received funding through grants, including The Lenfest Institute and The California Wellness Foundation. Revenues also include government funding to provide census information and public health information. In November, El Tímpano reached 1,200 people. About one in three have engaged with the platform, meaning they have sent out questions rather than just receiving information.

L.A. TACO

Last February, Javier Cabral, a Los Angeles native, a Mexican-American born to immigrant parents, and editor since 2019 of the James Beard award-winning platform L.A. TACO, published a story about Andres Santos, an elotero, a person who prepares corn at a food stand. Santos had worked in Highland Park for 23 years but, in response to the effects of gentrification, decided to go back to his native Mexico. The story, threading in entire sentences in Spanish and highlighting the popular expression ya estuvo (“I’ve had it”) is an example of how food can be used as a vehicle to bring visibility to the narratives of Mexican-Americans in Los Angeles.

L.A. TACO shines a light on the inequality and economic disparities that the Latinx Los Angeles workforce faces

“He is humbled, exhausted, and fatigued after getting up at 5 AM and single-handedly shucking and slicing the kernels off 500 ears of corn. He prepped up until 3 PM for his very last day of service,” wrote Cabral, describing the intensive labor, long hours, and hazards experienced by many immigrants in the informal workforce.

There are close to 10,000 food vendors in Los Angeles, many of whom are undocumented and identify as Latinx. Over the past eight years, the average cost of a house in Highland Park has more than doubled, from $352,055 to $797,250. Once a predominantly Latinx neighborhood, Highland Park has seen gentrification impact residents as well as the workers who cater to specific communities. In this case, the non-Latinx newcomers to the neighborhood did not share the same interest in Santos’ corn, which reduced his sales, eventually forcing him to give up his business.

“I was born and raised here,” says Cabral. “I’ve seen firsthand how my city is changing. I think the biggest topic is development, gentrification and homelessness. So, we find ways of telling these stories in a unique way.” Almost half of the population in Los Angeles is Latinx or of Latinx origin.

Among other topics, L.A. TACO shines a light on the inequality and economic disparities that the Latinx Los Angeles workforce faces. The outlet has also focused on addressing activism and racial injustice, working alongside Black voices and promoting unity among communities. In November, the site published “To Sheriff Villanueva”, which explores the #AdiosVillanueva campaign addressing the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department’s response to the killing of Andres Guardado, an 18-year-old Salvadoran who was shot by the police while working as a security guard. Since 2000, 53% of police fatalities were identified by the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner-Coroner as “Latino.”

Making a call for compassion and empathy for affected families, this piece gathers letters from activists from Black and Latinx communities who share their experiences of trauma at the hands of law enforcement on behalf of their sons. The letters speak to the systematic racism, impunity, lack of accountability and grief families are subjected to every day. “With the politicization of their deaths often follows the dehumanization of their lives,” wrote contributor Juliana Clark. “Too quickly, the public can forget that these men were once as real and vibrant out in the world as we all are.”

Once a Mexican territory, Los Angeles is in many ways culturally Mexican or Chicano, a chosen form of identity of Mexican-Americans. “Tacos are necesidad,” says Cabral, “L.A. is the city of tacos. Regardless of your income, everyone eats them and loves them. We celebrate the taco lifestyle.”

For the past couple of years, the independent platform has survived on donations from readers, who in exchange receive discounts and perks at restaurants that partner with L.A. TACO. However, the platform’s financial situation is far from what is needed to produce content or maintain staff. As Cabral puts it, L.A. Taco doesn’t make money, it “grinds by.”

TODAS PR

Todas PR was founded in the midst of a crisis. In 2017, Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, leaving over 10,000 residents jobless, including investigative journalist Cristina del Mar Quiles.

For some time, del Mar Quiles had been thinking about starting a feminist outlet to fill a gap in the Puerto Rican media landscape. In December of 2017, only three months after Hurricane Maria, del Mar Quiles and a handful of collaborators launched Todas PR.

The project, a labor of love from a team who all have side jobs, brings the voices of women and nonbinary folks and the issues that affect them to the Puerto Rican social and political landscape, focusing on stories of individual and collective fights in culture, politics, environmental issues, and sexuality. “Anything can be looked at through a gender-equality lens,” says del Mar Quiles. “For example, pension cuts are traditionally understood as something that mostly affects men, but this is untrue. Women are carrying all of this on their shoulders.”

In July, Todas PR published a piece that explains how pension cuts have affected women who support their families. Written by collaborator Némesis Mora Pérez, the story unpacks how female heads of families, who also have to tend to their children and grandchildren, are suffering the cuts by threading personal narratives with an up-close look at the short- and long-term effects of pension legislation.

Other issues covered by Todas PR include increasing rates of femicides and domestic violence. A piece by contributor Adriana Díaz Tirado explains how La Red de Albergues de Violencia Doméstica en Puerto Rico, shelters for women who have faced domestic abuse, are saving lives during lockdown. This service-journalism piece spotlights the gender violence that has been happening during the coronavirus pandemic. It provides a list of contacts and shelters to which women who are at risk can turn.

The platform continues to grow but is still in search of a revenue model. “We must make decisions and figure out if we want to be an NGO,” says del Mar Quiles. “The biggest challenge is to make independent media something sustainable.”

“¿QUÉ PASA, MIDWEST?”

“¿Qué Pasa, Midwest?” is the first bilingual podcast from the Public Broadcasting Station WNIN in Evansville, Indiana. Since 2016, it has been telling personal stories that affect Latinx communities in the Midwest, tackling topics such as Latinxs in the electoral process, music and identity, the challenges of healthcare, and crossing the border. Hosts and interviewees merge English and Spanish in an attempt to bring inclusion and foster education among different groups.

The project began while Paola Mazizán, founder and producer of ¿QPM?, was an intern at WNIN and noticed the lack of content directed to Latinx communities in the Midwest. From 2010 to 2019, the Midwest had an 18% growth in its Latinx population.

Mazizán made the case to Steven Burger, vice president of the station. With the support of grants from the likes of the Google Podcasts program from PRX, the station decided to try a podcast that would allow the target audience, many of whom are low-income factory and farm workers working long hours or even night shifts, to listen during their own time.

Episode 13 of season one, “Searching for Identidad,” unpacks an identity crisis by telling the story of Amy’s grandfather who, due to an abusive childhood in Mexicali, left the country as a young adult and enrolled in the U.S. military. Once in the U.S., people started assuming that he was Italian, an identity that he embraced through a friend. He never corrected them and for years Amy thought this was true.

“¿Qué Pasa, Midwest?” hosts and interviewees merge English and Spanish in an attempt to bring inclusion and foster education among different groups

“I want to learn Spanish. I want to learn to cook Mexican food and all of those things. Is that okay with you?” Amy asks her grandfather during the 10-minute episode. “If you have to do that, do it,” her grandfather replies, “but you have your own other background, don’t forget it, that we need to have the white part of it.”

This story debunks a common narrative in which immigrants always keep traditions and customs with pride, longing for their homeland. Here, however, cultural assimilation into whiteness — renouncing cultural heritage, language and an entire identity — is the priority. “My grandfather fell in love with this country via the military and then became a police officer, places where whiteness really does mean something special,” says Amy.

“They ignore us as a region,” says Mareea Thomas, co-producer of ¿QPM?, who is African-American, of mainstream news coverage of people of color in the Midwest. “They talk about California, Texas, New York, the coasts, and here people dip their toes in the water but they’re not really going into the communities and figuring out what people really think.”

Reporters at ¿QPM? and similar outlets around the country are starting to change that by elevating the stories of Latinx communities.

Correction: This article has been updated to amend a quote from Graciela Mochkofsky, which had been incorrectly transcribed.