Graduating from the University of Chicago in 1937, John G. Morris began his illustrious career in photojournalism as an office boy in the mail room of Time-Life. Over the next half century he played a major role in the golden age of photojournalism, as a picture editor on Life, The Ladies’ Home Journal, The Washington Post and The New York Times, and as Executive Editor of Magnum, the photographer cooperative. He has worked closely with great photographers, including Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Norris recounts his experiences in his memoirs, “Get the Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism.” Here are edited excerpts from the book.

Graduating from the University of Chicago in 1937, John G. Morris began his illustrious career in photojournalism as an office boy in the mail room of Time-Life. Over the next half century he played a major role in the golden age of photojournalism, as a picture editor on Life, The Ladies’ Home Journal, The Washington Post and The New York Times, and as Executive Editor of Magnum, the photographer cooperative. He has worked closely with great photographers, including Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Norris recounts his experiences in his memoirs, “Get the Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism.” Here are edited excerpts from the book.Copyright©1998 BY John Godfrey Morris. Reprinted by Permission of Random House, Inc.

I am a journalist but not a reporter and not a photographer. I am a picture editor. I have worked with photographers, some of them famous, others unknown, for more than 50 years. I have sent them out on assignment, sometimes with a few casual suggestions, other times with detailed instructions, but always the challenge is the same: Get the picture. I’ve accompanied photographers on countless stories; I’ve carried their equipment and held their lights, pointed them in the right direction if they needed pointing. I’ve seconded their alibis when things went badly and celebrated with them when things went well. I have bought and sold their pictures for what must total millions of dollars. I have hired scores of photographers, and, sadly, I’ve had to fire a few. I’ve testified for them in court, nursed them through injury and illness, saved them from eviction, fed them, buried them. I have accompanied unwed photographers to the marriage license bureau as their witness. Now I am married to one.

Photographers are the most adventurous of journalists. They have to be. Unlike a reporter, who can piece together a story from a certain distance, a photographer must get to the scene of the action, whatever danger or discomfort that implies. A long lens may bring his subject closer, but nothing must stand between him and reality. He must absolutely be in the right place at the right time. No rewrite desk will save him. He must show it as it is. His editor chooses among those pictures to tell it as it was—or was it? Right or wrong, the picture is the last word.

Thus the serious photojournalist becomes a professional voyeur. Often he hates himself for it. In 1936, Bob Capa made a picture of a Spanish Republican soldier, caught in the moment of death. It is one of the most controversial images of the 20th Century. Capa came to hate it.… Don McCullin, the great English photographer who has covered conflict on four continents, says simply, “I try to eradicate the past.” He is speaking of how he must deal with what he has seen, because, in fact, he has done his best to preserve the past. And Eddie Adams, whose Pulitzer Prize-winning 1968 photograph of the execution of a Vietcong prisoner by Saigon’s chief of police is a kind of ghastly updating of Capa’s image, says only, in his trademark staccato, “I don’t wanna talk about it.”

The picture editor is the voyeurs’ voyeur, the person who sees what the photographers themselves have seen but in the bloodless realm of contact sheets, proof prints, yellow boxes of slides, and now pixels on the screen. Picture editors find the representative picture, the image, that will be seen by others, perhaps around the world. They are the unwitting (or witting, as the case may be) tastemakers, the unappointed guardians of morality, the talent brokers, the accomplices to celebrity. Most important—or disturbing—they are the fixers of “reality” and of “history.”

Life Magazine

Life’s photographers had no desks, on the principle that they had no business sitting around the office, anyway. Instead, they had lockers in the Life lab on West 48th Street, a drab building that also housed a pharmacy. Only Margaret Bourke-White had an office there and a secretary. The Life lab had in fact begun as Bourke-White’s personal one, specified in her Life contract. The contract also gave her a printer and two assistants. Bourke-White was a notorious overshooter, working mostly with large (4-by-5-inch film) cameras and film packs. She demanded, and her printer saw to it that she got, excellent 11-by-14-inch enlargements, from full negatives. She did not, however, object when the editors cropped her pictures. Life’s other photographers, seeing these superb prints, were emboldened to demand the same quality for themselves. What was unfortunate was that they tended to try to imitate Bourke-White’s large-format technique, often “compromising” by shooting the square 120 format (2 1/4 by 2 1/4 inches) when lightweight 35-mm cameras were better adapted to reportage.

Photographers loved to work with [Life’s Hollywood correspondent, Richard] Pollard. He was unobtrusive, and he was helpful in small but important ways. One day, a Columbia Pictures press agent named Magda Maskel suggested photographing Rita Hayworth in a black lace nightgown that Maskel’s mother had made. Pollard and photographer Bob Landry met Maskel at Hayworth’s apartment. She knelt on a bed in the nightie, looking provocative, and Landry snapped away. Good, but something else might be done. Pollard spoke up: “Rita, take a deep breath.” That was it. The perfect frame. Not only did Landry’s photo become one of the most popular of all World War II pinups, it brought Hayworth a new husband. When Orson Welles saw it in Life, he determined to marry her. It may now seem odd, but Life did not immediately recognize the usefulness of “girl covers” in selling magazines. Life was six months old before the first such cover appeared—a chaste long shot of Jean Harlow, fully clothed, walking away from the camera. Six months later, Life ran its first mildly sexy cover, Peter Stackpole’s portrait of “The Prettiest Girl in Paradise.” The Paradise was a New York nightclub.

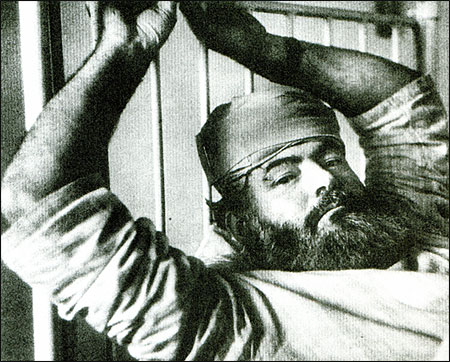

The aftermath of an all-night party given by Bob Capa landed Ernest Hemingway in the hospital.

In this frenzied season [in London, just before the Allied invasion of Naziheld France, Robert] Capa threw a party that remains memorable even by wartime West End standards. Capa never needed much inspiration for a party, but in this case he had much to celebrate—the successful appendectomy of his girlfriend, Elaine Fisher, known as “Pinky,” and the arrival in town of his old friend from Loyalist Spain and Sun Valley, Ernest Hemingway. Capa greeted him jovially as “Papa.” Hemingway, then 44, barrel-chested and full-bearded, was accredited as a Collier’s correspondent but irreverently sported a British battle jacket instead of the “Eisenhower jacket” that most of us correspondents wore. Capa proudly introduced his friend to the rest of us as “Ernest.” Hemingway spoke, not terribly intelligibly, in pure staccato.… When all the liquor was consumed—as I recall, it took us only until four in the morning to accomplish this—Papa left the party in the care of Dr. Peter Gorer,[who] promptly drove headlong into a water storage tank, sending Hemingway into the windshield and then a hospital bed. Capa and Pinky visited the old man a day or so later. With his head bandaged in a turban and his thick beard stuck out over the sheet, Hemingway resembled an Arab potentate. I sent along Capa’s picture of Hemingway in bed, and it made a full page in Life. I didn’t bother including the other shots on this roll—when Papa got up to head to the gents, Pinky playfully tugged on his hospital gown, revealing his wide rump. Capa thoughtfully recorded the moment on film, a picture that became my most amusing wartime souvenir.

When John Morris took this picture of a lineup of German prisoners during the Allied invasion of France he could only think, “You poor kid.”

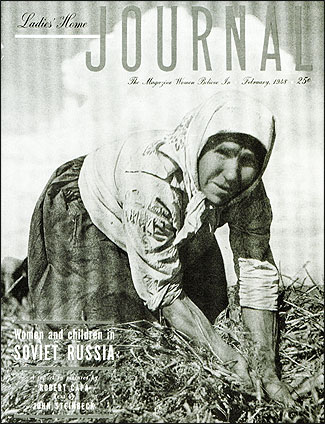

Ladies’ Home Journal

[As Picture Editor of The Ladies’ Home Journal] I proposed a series of covers featuring women who had never modeled. We offered photographers $2,000 for each cover accepted plus a $500 fee to the model, and we were soon flooded with submissions. Most were imitations of precisely the kinds of covers we wanted to get away from, but photographer Ruth Orkin, whom I had known when she was a messenger at MGM in Culver City, came through with a set of 35-mm transparencies of a New York City housewife named Geraldine Dent, taken at a fruit and vegetable stand. The picture that caught my eye was one where Dent’s bag of fruit had broken open and she had momentarily forgotten that she was being photographed. We used it for the March 1950 issue, which sold out—in fact, the Journal’s circulation hit an all-time high. It may have been the first time a 35-mm color slide was used on the cover of one of the “slicks.”

Magnum and the Picture Magazines

In 1990, the Duke of Edinburgh was given a private preview of Magnum’s “40th Anniversary” exhibition a few hours before it opened at London’s Hayward Gallery. His guides were Henri Cartier-Bresson and Burt Glinn, then Magnum’s Chairman and President. As he left, Prince Philip turned to Glinn for an explanation of how an organization of such diverse individuals managed itself. Burt flippantly replied that nobody really knew. Whereupon Prince Philip said, “It sounds to me like a perambulating disaster.”

He was not far off. The miracle is that Magnum has outlasted most of its major clients. The weekly Life expired in 1972 after 36 years; Look, Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post were already gone. These were the big four of the “golden age” of American magazine publishing, devoted to the mass audience advertisers love. But advertisers, like lovers, are fickle. They deserted the mass magazines for television, which delivered an audience of astounding numbers. First to go were the two magazines best known for fiction and articles, Collier’s and the Post. The photojournalism of Life and Look had hurt them both. In the fifties at Collier’s, and in the sixties at The Saturday Evening Post, new editorial regimes tried valiantly to don the cloak of photojournalism. We at Magnum began to profit from the change, but it was too late.…

On the night of March 18, 1960, a party was held in the office of Life’s Managing Editor, Ed Thompson, to mark the move from the “old” Time & Life Building on Rockefeller Plaza to the present one, the 48-story structure opposite Radio City Music Hall.… This party marked the end of an era. What few then knew was that Life, for the second year in a row, had lost money, thanks to the high cost of inflating its circulation amid falling ad revenues. The next year, Harry Luce, taking what I regard as bad advice, decided to change managing editors. Thompson was out, or rather kicked upstairs. George Hunt, his successor, asked me to lunch, confiding to me that he was firing Picture Editor Ray Mackland. But instead of asking me to take over, he asked my opinion of Dick Pollard. I recommended him, feeling like John Alden touting Miles Standish for the hand of Priscilla Mullens.

In England, too, the traditional picture magazines failed and floundered—Picture Post, Illustrated, Illustrated London News. On the Continent, picture magazines fared somewhat better, but only because it took longer for television news to catch on, costs were lower, and Europeans were more habituated to reading than watching. Magnum was founded at a time when those great picture magazines were alive and well. They provided the springboard for Magnum’s plunge into covering the world in pictures.

How did Magnum survive when they foundered? First of all, Magnum had an ésprit that is the very essence of photojournalism. It began with Robert Capa. Burt Glinn once said, “Capa reflected a lifestyle editors aspired to.” No argument. It was manifest in Capa’s understated courage—he gambled his life and treasure as fearlessly in Rockefeller Center as he had in Normandy. Capa’s style rubbed off, for better and sometimes for worse, on many of us in Magnum. At the weekly Life, to me the greatest of all picture magazines, this was implicitly acknowledged by the fellowship accorded to Magnum people on all levels. The Magnum spirit—the French call it “mystique”—also affected other magazines. Eve Arnold and Burt Glinn were favorites at Esquire, Brian Brake at National Geographic. Holiday, under the leadership of Editor Ted Patrick, Art Director Frank Zachary, and Picture Editor Louis Mercier, often turned over entire issues to Magnum to illustrate. Henri Cartier-Bresson, Elliott Erwitt and Burt Glinn were their favorites.…

The main reason Magnum survived even though the picture magazines did not was that by the mid-50’s, first in New York, then in Paris, Magnum had many clients for “corporate” work and a few for all-out advertising. The more enlightened companies gave us loose guidelines. Schlumberger, for example, simply wanted documentation of its international operations for its house organs. The editorial requirements of Standard Oil’s slick magazine The Lamp, which gave major assignments to Bischof, Rodger, Cartier-Bresson and others, seemed no different from those of Fortune. In retrospect, however, it can be seen that in the postwar period the big oil and auto companies changed the face of America, corrupting city councils, state legislatures and Congress to publicly subsidize highways, ripping cities asunder, and violating virgin lands. Some of the damage has been repaired, but America’s railroads, whose lobby was impotent and which also faced indirect public subsidy for the airlines, are probably ruined forever. Magnum played its modest part in this, as did Roy Stryker’s Standard Oil photographers.

The New York Times

On Sunday, September 14, [1967] Lawrence “Larry” Hauck, the bullpen’s weekend editor, went to the Picture Desk as usual, asking, “What have you got for the second front?” Unwittingly, the weekend picture editor brought him the new layouts. Hauck saw one on “The Talk of Buffalo” by a young reporter named Sydney H. Schanberg, with pictures by Eddie Hausner. The layout was horizontal, just one story above the fold, no column rules. “Looks good to me,” Hauck said. “I’ll run it”—which he did, in the paper of Monday, September 15, 1967. Thus, accidentally/on purpose, was accomplished one of the biggest changes in makeup of The New York Times in all its history. We were off and running. [Assistant Metropolitan Editor Arthur] Gelb and I were given full control of the second front. Two or three times a day, I would see him striding toward me, a few sheets of copy paper in hand, to ask, “How good are the pictures with this story?” Normally he accepted my picture judgment without question, but if I resisted and he was really keen on the story, he would throw an arm around me with an air of conspiracy: “You know, there’s a lot of interest in this story,” hinting that someone, perhaps [Metropolitan Editor A. M.] Rosenthal or even the publisher, had a stake in it.

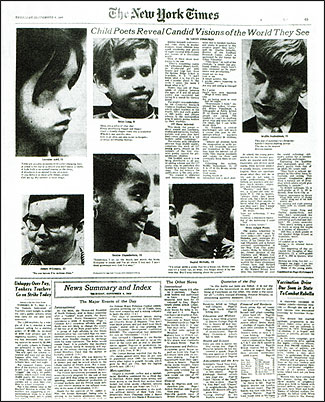

For the next six years, six days a week, Arthur Gelb and I controlled the best showplace in New York. Arthur’s curiosity and enthusiasm were almost child-like. The second front was our playpen. We could run almost any kind of story if the copy was charming and the pictures looked fresh. In retrospect, my favorites seem to have concerned children. Science writer Jane Brody discovered that “Children Scribble the Same the World Over”—an echo of the Ladies’ Home Journal’s “People Are People.” Reporter Lacey Fosburgh wrote about “Child Poets.” We ran their poems beneath sensitive portraits by Don Charles. Photographer William Sauro, who joined The Times after The World Journal Tribune folded, accompanied reporter Richard Lyons to a school that had been hit by German measles. Reporter Michael Kaufman and photographer Lee Romero told the story of an adventurous Harlem 10-year-old so eloquently that in 1973 their story became a book, “Rooftops & Alleys.” Reporter Joseph Treaster covered a rock festival in Connecticut with Bart Silverman. The participants thought nothing of appearing nude in front of the camera and set some kind of Times precedent when a bare-assed boy was shown striding across the foreground in a five-column picture.

The new approach soon spread to other pages. In the fall of 1967, Gelb gave reporter J. Anthony Lukas three weeks to research the background of a young woman named Linda Fitzpatrick. She had grown up in a proper suburban home only to become a radical terrorist who blew herself up with her own bomb. George Cowan did the layout; the story won a Pulitzer Prize. Soon reporters were aiming their stories for the second front, pleading with the Picture Desk for favored photographers, later dropping by my desk to get inspiration from the pictures and writing their stories to them—not unlike the practice at Life.

The September 15, 1967, second front of The New York Times, which opened up the page to picture layouts.

[National Editor] Gene Roberts helped me get a picture of the My Lai massacre into The Times. There was no press coverage of the March 16, 1968, slaughter of Vietnamese villagers by American troops, but Seymour Hersh of a small syndicate called Dispatch News Service finally broke the story on November 13, 1969. A week later, The Cleveland Plain Dealer published photos taken by a former Army photographer named Ron Haeberle. He claimed they had been taken with his “personal” camera and were therefore his own property. Haeberle had been giving slide shows to civic groups around Cleveland that had included a few of the massacre pictures. Apparently, there had been little reaction among the attendees. When Hersh’s story broke, Haeberle decided it was time to make some money, using his hometown paper as a showcase. With Plain Dealer reporter Joe Eszterhas, later to become one of Hollywood’s highest paid screenwriters, Haeberle flew to New York. The next morning, Gene Roberts and I collared the two entrepreneurs at the Gotham Hotel. We wanted only one picture, to document the story, but we had not decided whether we had to pay for it, much less how much to offer. Haeberle’s pictures were arguably government property. I was certain that Life was interested in the color, but my friend Dick Pollard, then the picture editor, wasn’t talking. I guessed that Life was unlikely to pay more than $25,000 (in fact, it paid $20,000). Roberts and I sounded out Haeberle and Eszterhas on the price of one picture for The Times. They hinted at $5,000, but we made no firm offer. They went off to conclude their deal with Life. In late morning, we received word that London papers, copying the photos from The Plain Dealer, were going ahead without payment, ignoring the copyright. The New York Post followed, in its early afternoon edition. Rosenthal decreed that it would now be ridiculous for The Times to pay. We would publish “as a matter of public interest.” The next day, November 22, The Times ran one My Lai picture on page three—downplayed to avoid sensationalism. The reaction was not what I had expected. Readers seemed as much incensed by our publication of the picture as by the atrocity itself. Newspapers that played the pictures big were condemned for being “un-American”—The Washington Star even had complaints of obscenity because some of the child corpses were naked.

I knew I would never make The Times a picture newspaper, but I was determined to show that more and better pictures would bring new readers to our world report. This meant coaxing the 30-odd foreign correspondents to take responsibility for getting pictures to accompany their feature stories. My foremost ally was Times Saigon correspondent Gloria Emerson, whom I had first known when she covered the Paris collections. She was the most sophisticated of all Times correspondents about pictures and photographers, and the most demanding. Coverage of the Vietnam War became her obsession. She saw it in the most basic human terms: “The war began like this: one man died, then another, then one more, then the man next to that man. The dying was one by one.”

Gloria was a class act, as much at ease when hitching a ride on a Honda as striding down the rue Saint-Honoré, but she did have a tendency to take one over.

The Crisis In Photojournalism

If there is a crisis in world photojournalism today, it is a crisis of editing and publishing, not of photography. We have thousands of magazines, some of them excellent and a few very profitable, but most are edited by their readers. Nowhere is this clearer than in France, where Paris Match, currently the world’s most sophisticated popular picture magazine, is also one of the most shameless. The August 2, 1997, Match cover was headlined: “Diana: Le Baiser” (“Diana: The Kiss”), with a sequence of color pictures devoted to the Princess and her Egyptian playboy boyfriend, Dodi Al Fayed, in their bathing suits, billed as “Exclusif: le reportage qui bouleverse la famille royale” (“the reportage that deeply distresses the royal family”). Three weeks later Match ran a chaste black and-white portrait by Patrick Demarchelier on its cover, “courtesy of Harper’s Bazaar.” Inside, 50 unbroken picture pages told Diana’s life story—with substantial assistance from the detested paparazzi. Perhaps this one issue of Match best demonstrates the clear editorial and public ambivalence concerning the ethics of photojournalism. Had photographers not so covered her, people throughout the world would never have come to know, love, and—ultimately—mourn their princess.

On that fateful night of August 30, 1997, photographers from Gamma, Sygma, and Sipa joined the paparazzi in pursuit of Princess Diana. In the soul-searching that followed her death, Gamma’s cofounder Raymond Depardon said he could not help but feel ashamed of the course taken by his former colleagues, although he blamed today’s relentless commercial pressures. “It is up to each [journalist] to determine his own conduct,” he said, adding that he himself had abandoned long-lens photography. Nevertheless, he warned that candid, unposed pictures should remain the goal of photojournalists: “These are the images that permit us to understand our times…. All the great [photographers] have worked this way, photographing in the street, without asking permissions.”

Unlike Henry R. Luce, who had the courage of his convictions, today’s editors watch to see what sells, just as today’s politicians adapt their policies to the polls. The line between journalism and entertainment is blurred. Most—thankfully, not all—American newspapers are more and more insular, ignoring the world. Fewer than half the pages in most publications inform the reader; the majority are there to sell something. Only National Geographic, among major magazines, runs picture stories unbroken by advertising. No wonder serious photographers have turned to producing books and exhibitions.

I cannot help but admire the courage and dedication of today’s roving photojournalists. It’s not just [David and Peter] Turnley. Look at the pictures by James Nachtwey and Susan Meiselas of Magnum, Anthony Suau and Stanley Greene of Vu, and Christopher Morris of Black Star—to name only some Americans. They are an endangered species, as a report of the New York-based Committee to Protect journalists makes clear. In 1996, 27 journalists were killed and 185 were imprisoned in the pursuit of their duties throughout the world.

Television and Print

It is fashionable to blame television for the problems of print journalism, but I refuse to play that game. Television and print should not be journalistic adversaries. They complement each other. When it comes to a breaking story of worldwide significance, television is now the indispensable medium. In 1989 we watched breathlessly the protests in Tiananmen Square and the breakup of the Berlin Wall; the next year it was Boris Yeltsin standing on a tank in Moscow to confront a Russian coup. The world’s statesmen now routinely form judgments based on such images. Perhaps someday world standards of photojournalism will reach the point where international conflicts will be covered evenhandedly by journalists from competing sides. This has happened to a small extent in Bosnia, in Chechnya and in Palestine following the birth of intifada. It is one of the hopeful aspects of the growing outreach of World Press Photo. As of now, the goal of evenhanded world coverage is attained regularly only at the Olympics—and rarely at the United Nations. Once the photojournalists of all nations become equally well equipped—not just with cameras, lenses and film but with visas and credit cards—new dimensions will emerge in the coverage of conflicts.

The Electronic Future

One thing photojournalists can do very well is attract attention. There are plenty of things that need it: the shameful condition of schools and hospitals, defective products, threats to the environment. There are new inventions and good ideas, and not just in our own country. Photojournalism, by focusing the world’s attention on one individual, personalizes history as never before, making it comprehensible to everyone. In Vietnam, it was Nick Ut’s picture of a little girl running from napalm: in Colombia, it was Frank Fournier’s picture of a girl slowly being engulfed in volcanic mud; it was David Turnley’s picture of the crying sergeant and the body bag. Too often attention is instead focused on the same old celebrities.

To view transient images is not enough. To truly comprehend takes time, and studied comparison. Fortunately, the world now has some assurance that visual records will be preserved electronically and made available to all—first on screen and then, selectively, in print. We stand to gain an astounding museum without walls. The child of the future can become a picture editor by simply choosing from a daily menu. It will be the task of tomorrow’s teachers to whet, and refine, that appetite.

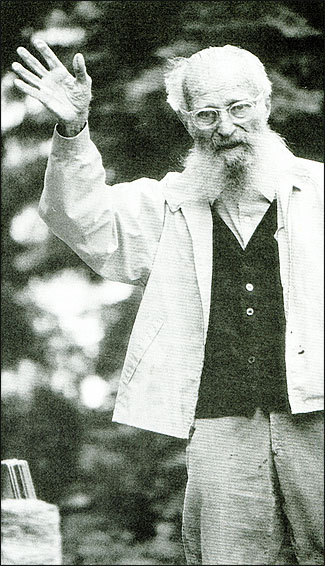

When Edward Steichen waved good-bye at his home in Connecticut one summer day in 1972, John Morris knew instinctively that he would never see him again. © Oliver Morris.