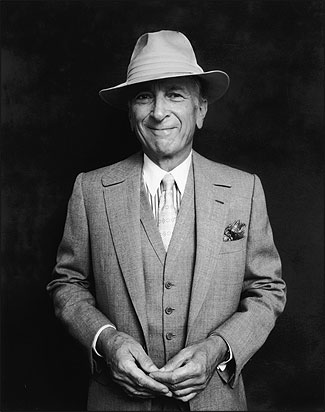

Invited by the Nieman Foundation, Gay Talese recently spoke at Harvard’s Writers at Work series in conversation with Esquire writer at large Chris Jones. His remarks have been edited for clarity and brevity. The full transcript is available online at Nieman Storyboard.

One of the problems of journalism today is how we are narrowing our focus and becoming indoors in terms of internalizing our reporting. The detail is what I think we're missing.

You have to be there. You have to see the people. Even if you don't think you're getting that much, you're getting a lot more than you realize.

People I like to write about are people who have had a history of ups and downs.

If you get to know your characters well and introduce them with your writing well enough that the reader will identify with them, or at least have a sense of them through your skill as a writer and a reporter, you've achieved much of what a fiction writer does.

Even as a young reporter I would think, why can't I do what short-story writers do or as novelists do, which is write scenes?

After you've gotten it right, then how do you go about

communicating the facts to the reader? That's where creativity takes its role in nonfiction: storytelling.

If you're an outsider you're the perfect journalist.

I don't think you know almost until the piece is published whether it's publishable.

In one way I can say I waste a lot of time; it's part of my occupation; I'm an occupational time waster because so much of what you do doesn't immediately measure up.

When I worked on The New York Times in the old days, those guys that got it right weren't necessarily lyrical figures in the world of literature—they were boring. They got it right, but they were the paper-of-record people. If you weren't a dazzling stylist it didn't make a bit of difference; in fact they suspected anyone who might be called a stylist in those days.

If you lie, you get kicked out. And the people who kick you out are your colleagues.

I save everything. I have a basement, what used to be an old wine cellar, and I have dozens and dozens and dozens of filing cabinets, and it's all in order, day by day, month by month, year by year, and there are big signs telling you what year you're in.

The press box in the 1950's was the era of alcoholism in journalism. You don't see any drinking going on anymore. You don't see any smoking. Fornication is out. Everything is out.

I don't think I've learned anything in terms of technique. It's as hard now as it was for me then.

Paige Williams, a 1997 Nieman Fellow, teaches narrative writing at the Nieman Foundation.

|

| Gay Talese, even as a young reporter, was drawn to writing scenes, as short-story writers and novelists do. Photo © Joyce Tenneson. |

One of the problems of journalism today is how we are narrowing our focus and becoming indoors in terms of internalizing our reporting. The detail is what I think we're missing.

You have to be there. You have to see the people. Even if you don't think you're getting that much, you're getting a lot more than you realize.

People I like to write about are people who have had a history of ups and downs.

If you get to know your characters well and introduce them with your writing well enough that the reader will identify with them, or at least have a sense of them through your skill as a writer and a reporter, you've achieved much of what a fiction writer does.

Even as a young reporter I would think, why can't I do what short-story writers do or as novelists do, which is write scenes?

After you've gotten it right, then how do you go about

communicating the facts to the reader? That's where creativity takes its role in nonfiction: storytelling.

If you're an outsider you're the perfect journalist.

I don't think you know almost until the piece is published whether it's publishable.

In one way I can say I waste a lot of time; it's part of my occupation; I'm an occupational time waster because so much of what you do doesn't immediately measure up.

When I worked on The New York Times in the old days, those guys that got it right weren't necessarily lyrical figures in the world of literature—they were boring. They got it right, but they were the paper-of-record people. If you weren't a dazzling stylist it didn't make a bit of difference; in fact they suspected anyone who might be called a stylist in those days.

If you lie, you get kicked out. And the people who kick you out are your colleagues.

I save everything. I have a basement, what used to be an old wine cellar, and I have dozens and dozens and dozens of filing cabinets, and it's all in order, day by day, month by month, year by year, and there are big signs telling you what year you're in.

The press box in the 1950's was the era of alcoholism in journalism. You don't see any drinking going on anymore. You don't see any smoking. Fornication is out. Everything is out.

I don't think I've learned anything in terms of technique. It's as hard now as it was for me then.

Paige Williams, a 1997 Nieman Fellow, teaches narrative writing at the Nieman Foundation.