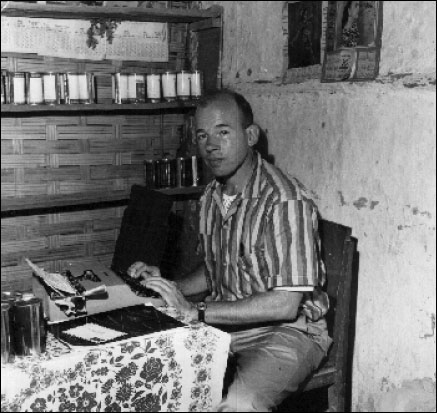

Richard Dudman in Laos in 1959, his first assignment in Southeast Asia.

Technology has changed my life as a journalist. How to get a story, of course, has changed a lot. But how to get the story to the paper is what I want to discuss.

Forty-five years ago, when I was a young Washington correspondent for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, then a p.m. paper, I would type my story at night at my upstairs desk on my old Underwood upright. I would keep a carbon copy, tape the original to the front door, and telephone Western Union. Early the next morning, I would telephone the wire desk in St. Louis to be sure the story had gotten there.

On my first foreign assignment for the paper, the Guatemalan revolution in 1954, I would type my stories on my portable Olivetti and hand them to some kid who for a few bucks would promise to carry them on horseback to the RCA office in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, where I had shown my credit card to a clerk. Most of the stories got through, including my account of the decisive battle of Chicamunga.

On an assignment to Northern Ireland, I dictated my story over a poor phone connection in a Belfast kitchen to the managing editor’s secretary in St. Louis. He kept telling me my voice was fading. I spoke louder and louder. He couldn’t seem to get the part about the three little Protestant school girls who were chanting, “Buy a penny rope and hang the fucking Pope.” To get it through to him, I finally had to shout it at the top of my lungs. But of course the paper wouldn’t print such a thing.

Covering the Vietnam War, I often had to make two carbons, one for myself and the second for the censor. At the telegraph office, a Vietnamese man, who could speak only a little English, would punch the story into a Telex machine. If I was lucky, I could see a printout and send corrections. What with errors in punching and trouble from the censor, my stories sometimes were badly mangled.

On presidential campaigns and foreign presidential trips, I would dictate stories to St. Louis out of my head, a paragraph at a time, relying on a few scrawled notes to remind me of points I wanted to cover. When an overseas phone connection was bad, I had to shout, “Working! Working!” over and over again to keep the operator from cutting me off.

Reporting from Washington, I could punch my stories in the daytime on a dedicated teletype line to St. Louis or else hand them to Estie or Helen-Marie or Peachy, who would punch them and often would catch my errors.

Everything has changed since then. I’ve been retired for 20 years and know nothing of the portable phones which enable foreign correspondents to connect instantly with their editors by satellite.

But the new high-tech era helps me at our summer place on an island three miles out in the Atlantic. I have been writing two editorials a week on a freelance basis for the Bangor Daily News. I type them into my Apple iBook, cut and paste them onto an email message, and send them instantly to the editorial page editor. Each day around noon, after the mail boat has arrived, I can pick up my paper at the village post office and see whether one of my editorials has made the page. If the mail is late, I can check the morning’s editorials on the News’s Internet site.

If it were not for the Internet, I would be out of a job. I doubt that the News would be able to provide a dictationist, and it probably would find fax too cumbersome.

Richard Dudman is a 1954 Nieman Fellow.