Teeming streets of Hanoi. Photo by Pham Ba Hung.

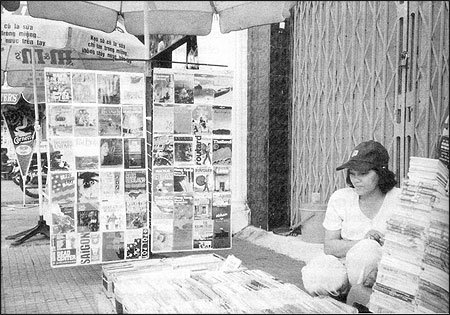

A woman in Ho Chi Minh City offers a myriad of publications at a newsstand. Photo by David Lamb.

I fell into a pleasing routine during my four years in Hanoi. Like a million or so Vietnamese, I’d get on my bike early each morning and head downtown through the capital’s congested streets. A couple of blocks from my office, I’d stop at Au Lac Café and take a seat on the patio. A young waiter named Dia would bring me a cup of Vietnamese coffee and a copy of the English-language Vietnam News. It was a quick read, devoted largely to extolling the virtues of the Communist Party. But every now and then, I’d find something that surprised me—an article on official corruption or one on slumping exports, the sluggish pace of economic reform or the widespread use of drugs.

No one was going to confuse the Vietnam News with The Times of London. The news media remain an arm of government in Vietnam, and the nation’s 80 million people—whose literacy rate is a remarkably high 91 percent—clearly are only told what the Politburo wants them to know. Still, the press in Vietnam is freer than it was a decade ago. Like the country itself, it is in transition, moving with timid steps toward a free-market economy and perhaps, farther down the road, the freedom of expression that Vietnam’s constitution says is every citizen’s right.

Despite widespread self-censorship and the omnipresent shadow of Big Brother, the country’s 7,000 journalists routinely report these days on issues ranging from smuggling to prostitution. Granted, these are subjects sanctioned for discussion by Hanoi, but in a country where the government controls all publications and the Party’s Commission for Culture and Ideology meets every Tuesday to decide what issues people will be told about in the week ahead, such coverage would have been unimaginable in the dark years of the early post-war period.

“There is no question we have more freedom today,” said Nguyen Duc Tuan, an editor at Lao Dong (Labor), which has 80,000 daily readers and sells for the equivalent of 12 cents. “In the old days, we basically had no news and papers weren’t much more than crude mimeographed Party newsletters. Now, reporters like to see how far they can push and still get their stories published.”

The transformation of Vietnam’s press began in the mid-1980’s, when famine threatened the country and the economy was in a tailspin. Reluctantly, the leadership followed China’s lead and started moving away from rigid state control of every aspect of life to embrace free enterprise. Subsidies that had kept newspapers in business were dropped, and suddenly editors had to compete for advertising and readers if they wanted to survive.

Editors (most of whom are Party members) became responsible for the content of their publications. Business managers started harping about the need to turn a profit. Newspaper layouts got brighter, content livelier. Readership soared. So did the number of newspapers and magazines—from just a handful in the 1970’s to more than 370 today. Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) alone now has 35 newspapers and periodicals; Hanoi has 10. They range from old-fashioned mouthpieces like Nhan Dan (the People) to dailies like Tien Thong (Pioneer), which attracts younger readers with a mix of sports, culture, crime and national news. Additionally, foreign publications such as the International Herald Tribune, Time and Newsweek are now readily available in Vietnam’s two major cities.

It is also significant that journalism is no longer a high-risk job in Vietnam, in contrast to much of the world where 37 journalists were killed last year [2001] and 118 imprisoned as a result of their work, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Reporters don’t disappear in the night in Vietnam, don’t get tortured, and very rarely get arrested. Editors occasionally run afoul of the authorities, a misadventure that can cost them their jobs, but not their lives. If an article offends, authorities yank it from the newsstands.

A couple of years ago Tuoi Tre (Youth) magazine published a poll it had taken to determine what individuals the post-war generation most admired. Predictably, former President Ho Chi Minh was the most popular (39 percent), followed by the legendary general, Vo Nguyen Giap (35 percent). But one man had been dead for more than 30 years and the other was nearly 90. Only one non-retired Vietnamese made the list, Prime Minister Phan Van Khai (three percent). Hillary Clinton received as many votes as Khai did; President Bill Clinton got twice as many. Bill Gates was seven times more popular than anyone in the Politburo was. The Party was appalled. State censors destroyed the print run of 120,000 copies within hours of the magazine appearing on the newsstands.

With the Party’s influence fading as the post-war generation questions whether communism is the best path toward development, it is hardly surprising that Hanoi wants to keep a tight control on the flow of information—so tight that Vietnamese editors and reporters are seldom allowed to travel abroad to study journalism. The last thing Hanoi wants is feisty, challenging reporters intent on practicing real journalism. To officialdom, journalists should see themselves “as frontline soldiers on the cultural ideological battlefield.” As in many developing countries, Vietnamese reporters are expected to promote the national agenda, not agitate for reform. “Being a true journalist,” former Party chief Le Kha Phieu also said, “it is necessary to reflect the thoughts and the wishes of the public and be on the right political track oriented by the Party.”

Sadly, Vietnam’s poorly paid reporters (weekly starting salary is about $30) seemed to have bought into the Party line. I say “sadly” because I met so many bright, inquisitive and ambitious young Vietnamese that it was difficult to understand why the reporters among them didn’t hold their profession to a higher standard. Perhaps it was because they considered journalism merely a job, not a noble calling, and perhaps because no one had ever taught them how important a role the media plays in a truly free society.

“I think we have all the freedom we need now,” one senior reporter told me, reflecting on the belief that economic advancement was, for the present, more important than democratic growth—and that one bore no relationship to the other. “Besides, no one has total freedom in the press. Were American reporters allowed complete freedom in the Gulf War?”

David Lamb, a 1981 Nieman Fellow, worked in Vietnam from 1968 to 1970 for United Press International and from 1997 to 2001 for the Los Angeles Times. He is the author of “Vietnam, Now: A Reporter Returns” (PublicAffairs, May 2002).