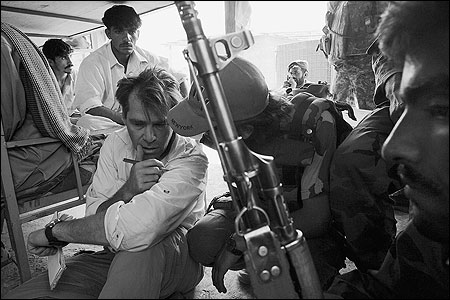

Boston Globe reporter Charles Sennott observes a local Afghan commander and U.S. Army major listening to tribal elders talk about how some of the village residents had been wrongly detained as Taliban sympathizers. Kunar Province, Afghanistan. Photos by Gary Knight/Courtesy VII agency.

Last summer, I went straight from the warm afterglow of a Nieman Fellowship to the searing heat of Pakistan and Afghanistan. My first assignment after "the year of living comfortably" would take me back to the rugged border of Pakistan's NorthWest Frontier Province and then into Afghanistan to document successes and failures and challenges that lay ahead five years into what Washington had come to call "the long war."

It had been five years since I reported in Afghanistan, covering the U.S.-led offensive against the Taliban and al-Qaeda in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks. This reporting trip — timed to coincide with the fifth anniversary of September 11th — was, as my editors saw it, a chance for me to report on the flawed and futile hunt for Osama bin Laden and the resurgence of the Taliban. It was also an opportunity to explain to readers how the war in Iraq was draining resources from the U.S.-led coalition's struggle in Afghanistan, which was referred to with bitterness as "the forgotten war" by Army National Guard Staff Sgt. Michael Nye, a 29-year-old soldier I met during my time there.

To provide readers of The Boston Globe with closer connections to the story, I decided on a different approach to reporting. Working with Deputy Managing Editor for Projects Mark Morrow and a Globe Web site multimedia producer, Scott LaPierre, I crafted an interactive map that readers could use to trace my journey; by clicking on key points along the way, they would accompany me through the words of a daily Weblog I wrote, in which I recorded my impressions and commentary.

To make all of this happen, I packed a state-of-the-art digital sound recorder, microphone and headphones, along with my laptop, a satellite telephone, a Thuraya handheld satellite, a GPS device, a combat helmet, and a Kevlar vest. Gone are those days when a brick of notepads, a box of pens, and a Tandy TR-80 powered by four C batteries, along with those weird looking black, rubber couplers to connect to a phone line, fit snugly in the corner of a suitcase.

Now, in my impossibly heavy duffle bag, I carried what I'd need to capture natural sound, conduct interviews, and record my impressions. Our plan was to weave all of this together — with images — in a multimedia presentation when I returned; if the sound was good enough, we'd work with The World, a partnership of the BBC and Public Radio International, to produce a radio documentary. Gary Knight, one of the founders of the VII photo agency and a photojournalist whose work in conflict zones is well known and widely respected, accompanied me on some of this trip.

Multimedia reporting was new to Gary and me, so our growing pains were awkward. But our learning had to happen at an accelerated pace. For a longtime print reporter, getting accustomed to juggling digital equipment, monitoring record levels, and taking in my surroundings through headphones wasn't easy. My first job after college was as a radio reporter for an NPR affiliate; immediately I noticed the remarkable light weight of the new digital equipment compared with the extinct Nagra reel-to-reel recorder I'd once shouldered. But even with this equipment in hand, during the day I primarily relied on my notepad and pen. When there was a richness of sound or a strong interview, I'd strategically break out the digital recorder.

Gary had challenges in adjusting, too, since he wasn't just shooting a single story; it would be his visuals that would propel our narrative account forward once it was up on the Globe's Web site. This meant he was photographing not only what he saw happening around us, but also he had to take pictures of me being a reporter at key moments.

There were times along the back roads of Afghanistan and Pakistan when I remembered how much I loved gathering sound and "hearing" a story. Now I was developing a vivid audio portrait, and my intense awareness of sound was strengthening my writing, too, as I listened closely to the echoing of the call to prayer; the thunder of outgoing artillery; the wind-swept silence of the rugged peaks along the mountain border, and even the absurd swing and "thwack" of a golf ball at the Qargha Golf Club on the outskirts of Kabul at a surreal golf tournament known as the Kabul Classic played on a hardscrabble course where al-Qaeda once had a training camp. I recorded voices, too, ranging from the all-American twang of a self-described "jarhead" in the U.S. Marine Corps to an Afghan adolescent who admired Osama bin Laden and described him as "a great leader of Muslims."

Layers of Reporting

In my Weblog, I recorded impressions of our journey. At times, I offered comparisons with my first reporting trip in Pakistan 10 years earlier when a nascent movement was gaining force in the region and those of us reporting the story started to use its name — the Taliban — in our stories. At the time, U.S. diplomats in Central Asia viewed the Taliban as a favorable alternative to the brutal warlords ravaging Afghanistan in the aftermath of the Soviet withdrawal. After September 11th, the United States set out to destroy the Taliban for providing sanctuary and support to bin Laden and al-Qaeda. In doing this, they were reemploying some of those same brutal warlords to get the job done. U.S.-led air strikes succeeded in toppling the Taliban regime in Kabul, but the operation ultimately failed to capture Taliban and al-Qaeda leadership and allowed many followers to escape.

Now, during the summer of 2006, the Taliban was in the process of reasserting itself as a force to be reckoned with in this region. Had I only been writing an article for the paper, the contextual information I could bring to the story — based on my reporting then and now — would not likely have been as accessible or as evident to readers as it was in this new format.

The Taliban had been born of the refugee camps and madrassahs, or religious schools, in Pakistan's storied North-West Frontier Province 10 years earlier. It seemed as fitting as it did disconcerting that the movement is being reborn in this same remote, lawless region. The arc of this story is striking, and it reminds any correspondent who has reported from this region over a period of years of the layers of history and tribal affiliations marbleized into the impenetrable, jagged peaks of the border.

After about 10 days of reporting in Pakistan, I crossed into Afghanistan on a commercial flight from Peshawar to Kabul. Our entry to the country was quite different than the harrowing landing I'd experienced with other Western reporters five years earlier when a rusted U.N. cargo plane slammed down on a tarmac cobbled out of corrugated metal in Faizabad, Afghanistan on or about September 21, 2001. (The smudged ink of a Northern Alliance officer's pen, marking the date in my passport, makes it hard to tell.) Back then we were surrounded by a group of men with long beards dressed in rags. They stared in utter disbelief at us with our satellite phones and laptops, just as we must have looked at them with the same stunned expression. We were from different worlds.

This time the first person I met was an Afghan-American high-tech entrepreneur smartly dressed in a pinstripe suit who was checking his e-mail with a wireless laptop as he waited at baggage claim. Contrasts such as this were stark. Recording the voices and sounds of this moment meant I could include them in the multimedia presentation and the radio pieces. They also made my writing for the newspaper series easier since the recordings gave me an audible memory.

As Gary and I journeyed through Afghanistan, we were mesmerized by the rugged and breathtaking majesty of the landscape. The place is unforgettable and intoxicating. Despite the danger, the land and the people have a pull as true as magnetic north. It is also an unfathomably complex culture, as impenetrable to Westerners as the terrain itself. In other words, we loved being there again.

Embedding With Afghan Forces

We wanted to be the first U.S. reporting team to embed with an Afghan National Army (ANA) unit. Neither of us had any interest in embedding with U.S. forces since we did not want to compromise our freedom to report what we saw and heard. Afghan and American officials laughed when we told them our idea of going into eastern Afghanistan with the ANA. But we did it anyway.

We ended up traveling with the ANA Third "Kandak," which is roughly the equivalent of a battalion. We traveled with them to a U.S. military FOB, or forward operating base, called Camp Joyce, that was connected to the 10th Mountain Division and an array of U.S. Army Reserve and National Guard units. A Special Forces unit was stationed there but mostly kept to itself. The ANA stayed in mud-brick hovels on the outer edges of the camp and were not allowed to eat in the mess hall. That's where we stayed, too.

Camp Joyce was in the village of Sarkani in the eastern province of Kunar. The troops here comprise the frontline of a futile and undermanned hunt for bin Laden. Intelligence officials in Washington, Rawalpindi and Kabul told us the trail was stone cold, with no good leads on the whereabouts of the most wanted man in the world for nearly two years.

Within a few hours of our arrival, Gary captured the essence of the situation beautifully in a photograph he took of a group of ANA soldiers. We were told they were on "look out," but we found them stripped down to T-shirts and asleep on rusted cots arranged on a peak that looked out over the breathless and perilous beauty of the Hindu Kush. It was a scene straight out of the old TV sitcom "F Troop." The ANA is notoriously underpaid and plagued with desertion rates that run as high as 50 percent in some units.

One night, the FOB was hit with rocket-propelled grenades. Maybe we'd been around too much of this stuff, but the distant bangs on the outskirts of the camp hardly stirred Gary or me from sleep. But the ANA response was hard to sleep through. The soldiers opened fire into the predawn darkness with an old Russian 50-caliber machine gun. Phosphorus tipped bullets looked like 4th of July sparklers as they lit up the rocky hills.

The next morning, the ANA soldiers in concert with the U.S. Army troops who served as "mentors" continued firing. The whole exercise, it seemed, was choreographed as a response for our reporting benefit. We cringed. The ANA firing in the rocky hills echoed high and thin and the hollow sound, which I recorded, seemed to capture the futility of this "long war's" search for bin Laden. They were firing at nothing.

Later in the morning, U.S. Army Major Fernando Rodriguez had his first cigarette and an idea. He decided rather than fire blindly into the hillside, several of his men and a platoon of ANA soldiers would take a convoy up into the tiny village that sat on a ridge looking down on the camp. Since it was likely that the villagers either knew about or were complicit in the attacks, Rodriguez wanted to go directly to them. Gary and I went along for the ride and documented Rodriguez and the ANA local commander interacting with a group of village elders.

A Meeting of Minds

The villagers spoke of their grievances, though they did not admit that they carried out the attacks or knew who did. Clearly they were letting the United States and ANA know that they had little incentive to help prevent such attacks. A tribal elder, Zar Said, stood up to offer a prayer and then explained that he and other men had been wrongly detained as Taliban sympathizers — they were, he said, devout Muslims, unjustly detained and mistreated by U.S. military personnel at a holding cell at the Bagram Airbase. Said told them he was released, but other men from the village were still there.

This moment offered a sort of epiphany. Here, American soldiers confronted directly how abuse of detainees by U.S. military troops could reverberate in insurgent attacks on them.

I recorded these sounds while Gary focused on the villagers' stony, distrusting faces. He captured the tribal elder praying, the ANA commander pleading for honesty, and Major Rodriguez listening intently to the tribal leaders and vowing to look into their claims. This encounter was a significant part of our report, and our ability to display it in these various dimensions made it a strong component of the Globe's multimedia presentation. And these moments, with the sounds offering easy passage into the narrative storytelling, became the focus of the radio documentary we did for The World.

By combining the reporting for my newspaper story with the ambient sounds and pictures, Afghanistan's story — with its complexities and nuances — could be conveyed to readers in more vivid and more powerful ways than can be captured on the printed page alone. With a story told from such a distant and foreign place, inviting people to immerse themselves in its many different dimensions made our journalistic account stronger. Pieces of what we brought home from this reporting trip have also been used in presentations I did at Harvard at the Kennedy School's Carr Center for Human Rights Policy and as part of a guest lecture for Divinity School Professor Harvey Cox's class, "Fundamentalisms."

I will continue to experiment with digital journalism. Perhaps a decade from now, when I look back at what we created this first time out, it might seem as rusted and creaky as that old Russian cargo plane on which I flew into Afghanistan a decade ago. And we can only wonder whether it will be in Afghanistan that correspondents will be taking their new digital gear 10 years from now, with the same need to illuminate what is happening there.

Charles Sennott, a 2006 Nieman Fellow, is a foreign correspondent with The Boston Globe's Special Projects Team and was among the first reporters on the ground in Afghanistan in the immediate aftermath of September 11th.