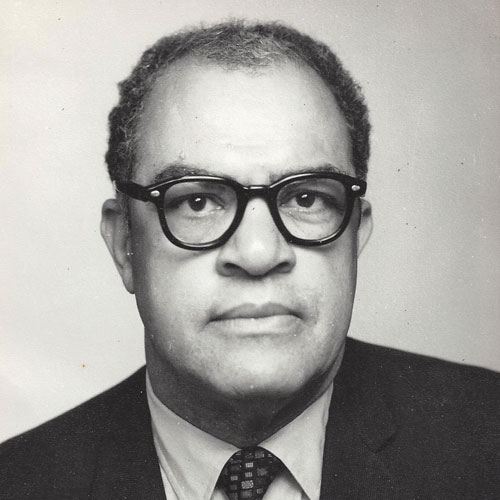

The first black journalist to receive a Nieman Fellowship, Martin (1916–2005) was a World War II correspondent. As city editor of the Louisville Defender in the 1940s, he advocated for desegregation in state parks. During a stint at the Chicago Sun-Times after his Nieman year, he covered civil rights and introduced the city to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Inestimable” describes the impact the Nieman Fellowship had on my father’s career and life. The jump from Louisville Community College to Harvard University was a mega-leap in terms of how he saw himself and life. The Fellowship offered a door through which he could pass into another world of possibilities. He and I would talk often about the courses he had taken and the professors he met, especially Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr., who would invite the Fellows over to his house on Sunday mornings for private conversations. Given the social times in the United States prior to Harvard’s invitation, an African-American journalist’s chances of entering into the world of the national press were slim. But armed with the most prestigious journalism fellowship on the planet, he appeared on the radar.

He certainly felt the burden of being the first black journalist to be accepted into the program. He also felt the relief of being accepted by his classmates as an equal. While his studies at Harvard were critical to the way he developed intellectually, the experience with his Fellows was even more critical to his career. To him, here were men of great intelligence who were themselves a study. He studied them and they him—iron sharpening iron. They became for him a confirmation that he could do anything his abilities would allow. The Chicago Sun-Times, partially a result of the Fellowship, was a place where men of like talent to those of the Class of 1947 were to be found. My father was at home with the Sun-Times.

My father said that he was influenced by being a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, so in a sense, he’s living on through me. In fact, he named me after the Fellowship. The burial jacket he wore had an emblem sewn onto the right pocket. It said “veritas.”

By Peter Nieman Martin, Sr., a minister and English-language instructor in Indianapolis