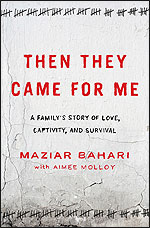

Maziar Bahari, a reporter for Newsweek, endured imprisonment and torture for his work as a journalist in Tehran. Photo by Hossein Salehi Ara/Fars News Agency/The Associated Press.

When Iranian security agents went for Maziar Bahari, a Newsweek reporter, in Tehran in June 2009, they awakened him in the early morning and ransacked his room as his 83-year-old mother stood by. Then he was blindfolded and the agents drove him to the notorious Evin Prison in northern Tehran, where they incarcerated him for close to four months. They tortured him to the point that at the age of 42 he considered killing himself.

In "Then They Came for Me," Bahari recounts in excruciating detail what it was like to be held in Evin Prison, an experience that his older sister, Maryam, and his father, Akbar, endured before him. Maryam, who was 10 years older than Maziar and died of cancer a few months before he was arrested, survived a six-year jail term that ended in 1989. Before the 1979 Islamic revolution, their father was incarcerated under the shah. Maziar describes how his father lost all of his teeth and his nails grew deformed because of the torture.

Unlike his father and his sister, who were involved with leftist opposition groups, the crime he was accused of committing involved his work as a journalist: He was arrested after he shot a video of government forces opening fire on protesters in Tehran on June 15, 2009. The footage was broadcast on Britain's Channel 4 News and NBC in the United States. "I detested revolutions," Bahari declares at the outset of his book, "… the most important thing to me was to be able to continue to do my work as a journalist." He grew up in Iran and lived under the strict control and restrictions of the Islamic regime. "I understood that a lack of information and communication among a populace leads only to bigotry, violence, and bloodshed," he writes.

In prison, his interrogators used the word Mohareb, which means "one at war with God," when they talked about his work as a journalist. It is, they told him, a crime that can be punishable by death. Ten days into his imprisonment and after enduring brutal beatings, they forced him to appear before the cameras of state-run television. He was told to confess about the role that reporters working for foreign media, such as he, had played in instigating the protests.

"You can be freed in a couple of days if you perform well," they promised him.

Doing this false confession crushed Bahari harder than the beatings had. Back in solitary confinement he hit his head against his cell's wall. "Bang. Bang. Bang," he wrote. "I hit my head hard against the faux marble wall again and again, ignoring the pain that crept up my neck. I deserved the pain. I had betrayed my family, my colleagues, myself." At last, he found the strength to stand and take a few steps. "It was hard to gauge how much time I spent pacing the small cell—maybe several minutes, maybe hours—but eventually, I fell to the floor again and curled the blanket around myself."

His freedom did not come for another 108 days. The beatings, long interrogations in the middle of the night, and solitary confinement continued during most of his detention.

Writing From Prison

Bahari's Evin Prison memoir is one of many written during the past two decades, most in Persian or English, others published in different languages. Each testifies to the paranoia of those who for more than three decades have held their grip on power by terrorizing their citizens. After summary trials following the 1979 revolution, hundreds of Iranians were executed. A decade later more than 3,000 political prisoners serving jail terms were secretly executed in the worst massacre in Iran's modern history. "Suddenly we noticed that our food rations began to increase. It became obvious to us that the number of those who needed to eat was shrinking," wrote Iraj Mesdaghi in his prison memoir "Neither Life, Nor Death."

In the past 10 years, hundreds accused of trying to overthrow the regime have been jailed. The charges have been vague, and judiciary officials, beholden to government leaders, tend to shroud the accusations in a wrap of national security. In Bahari's case, he was charged with trying to stage a velvet revolution; the courts tried him in abstentia and sentenced him to 13½ years in prison and 74 lashes. In 2009, 100 former officials, scholars and journalists were put on trial en masse in a public display of intimidation; all were accused of trying to topple the regime.

Iran leads the world in executions, with the highest number per capita, according to human rights groups. Since the antiregime protests in the summer of 2009, the number of executions has risen dramatically. Last year 542 people were executed, according to figures compiled by the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran (ICHRI), an independent organization based in New York. This year the regime has acknowledged publicly that it has executed 249 people, but according to Hadi Ghaemi, ICHRI director, there have been at least 229 more secret executions. The regime claims that most of those it executes are criminals with drug-related offenses, yet close observers contend that political prisoners are executed under the guise of criminal charges.

At the University of Toronto, Shahrzad Mojab, a professor of women's studies and adult education, has held workshops for political prisoners who survived the 1989 massacre, and she has helped publish dozens of horrifying memoirs in Persian. "The memoirs are a very important historical document," she told me. "The prisons were the first places that the regime had utter control, and it began formulating its first Islamic ideology and segregation policies there. Now these memoirs show this to us."

The paranoia of the early days of the Islamic revolution now drives the government's survival strategy. Any leeway to dissent challenges its authority, and so the regime uses violence as its foremost tactic to suppress dissent. Journalists pose a threat in the words and images they send across the nation's borders, and thus Bahari—and others like him—must be brought under the regime's iron rule.

Recently Iran's leaders have gone after foreign nationals, who, like Bahari, have then written about what they experienced. In "Saved by Beauty," the British-American author Roger Housden wrote about being picked up by security agents at Tehran's Imam Khomeini airport in February 2009 when he was about to leave the country after a brief visit. Agents took him to a hotel room in Tehran and kept him there for 36 hours before they charged him with collecting negative information about the country and warned that they could make him "disappear." Finally, they offered him a deal: go to work for Iran's security apparatus or land in Evin Prison. "We want you to give us information on philanthropic foundations that are active in Iran," he quoted his interrogators as saying. "We want the names of the Iranians involved." In a bid to save his life, Housden said he'd work for them.

The fate of Robert Levinson, a former Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent, who went missing in southern Iran in 2007, is still unclear. And it's been more than two years since three American hikers were imprisoned on spying charges; the female hiker was freed, but her two male companions remain in Evin Prison.

The Iranian agents took smiling pictures with Housden to use as blackmail before putting him on a plane. When he returned to New York, Housden ignored a contract the Iranian agents e-mailed him. Instead, he contacted the FBI and changed his e-mail address and telephone numbers.

Nazila Fathi, a 2011 Nieman Fellow, reported from Tehran for The New York Times until 2009, when she fled to Toronto and reported on Iran from there. She will be a Shorenstein Fellow at Harvard University's Kennedy School in January 2012.