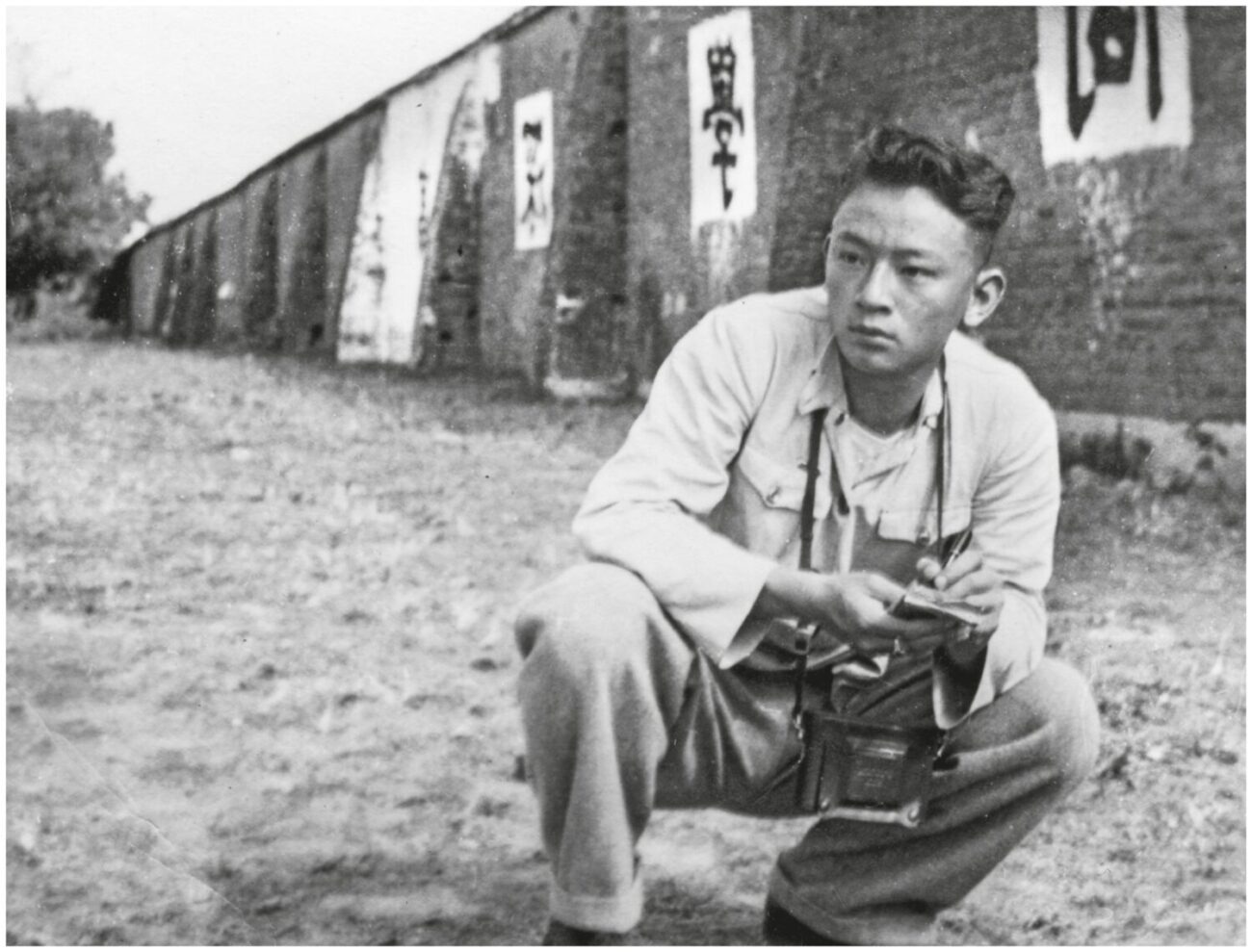

Edward Wong, who grew up in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., said his father never shared much about his life in China before immigrating to the United States. Over the years, Wong initiated more conversations, learning that, as a young man, his father once enthusiastically embraced Mao Zedong's Communist revolution, dropped out of college to join the People's Liberation Army, and hoped to serve in the Chinese air force during the Korean War. He eventually grew disillusioned with Mao’s regime, and made a daring escape to Hong Kong in 1962 before ultimately settling in Alexandria, Virginia.

Wong delves deeper into his father’s life story in his book “At the Edge of Empire: A Family’s Reckoning With China.” Tracing his family’s roots in Hong Kong and southern China, Wong weaves in his own experiences as a foreign correspondent in Beijing for The New York Times from 2008 to 2016. Through his journalistic work, Wong draws connections between his father’s experience and his own insights into China’s national ambitions, the country’s rise as a world power, President Xi Jinping's rule, and ethnic tensions in regions like Xinjiang and Tibet.

The idea for the book crystallized and took shape, Wong says, during his Nieman fellowship year in 2017-18. He spoke to the current class of Nieman Fellows and Nieman Reports about combining reportage with memoir, interviewing his father over several years, and researching his family history.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The structure for this book was something I thought through very carefully when I was doing my [book] proposal, and also with input from my agent who was editing the proposal. It was a challenge because I knew I wanted to tell two narratives in two different timelines. One is that of my father, and mainly focused on the 12 years that he lived in the People’s Republic of China. And for most of that time, he was dedicated to trying to realize Mao’s vision of China. And then the other part would be from 2008 onward to now, and my own experiences and reporting in China.

I did want the book to feel like there was movement through time for the reader. And I thought what I would do is to tell one of those narratives chronologically, which was my father’s narrative, and my experiences in China would then be interspersed among chapters that told his story. [My reporting experiences] would be paired with his chapters thematically, so there would be experiences that I had, or reporting that I did in contemporary China, that mirrored experiences that he had been through, and that would, in a way, still keep the reader on a chronological trajectory through China. But at the same time, it would also bring up this idea of echoes of history from different decades in China, from the 1950s to today, and I thought that that would allow me to express ideas of historical patterns that were taking place in China, especially in the current era of leadership under Xi Jinping, and how there are echoes of the Mao era under his leadership.

I think one of the most difficult things to tackle was the emotional turn in [my father’s] story, when he realizes that his dream of what he wanted to do in China would never be realized. He believed [there were] suspicions about him within the [Communist] Party and within the military. Partly due to structural factors within the party, he [knew] he would never win their trust the way he wanted to, combined with political forces that were at play that made him doubt the direction of the country, such as the great famine [of the late 1950s.] Mao’s purging of very senior leaders in the party — including top military commanders who my father looked up to. That all comes into play at the end of the 1950s and the early 1960s, when he has devoted a big part of his young adult life to try and serve the party, but then realizes that he’ll never be part of the system. He’ll always be an outsider, and not just an outsider, but someone who is suspected of being a potential traitor to the country. Trying to capture that sense of disappointment on his part and the emotional turn was a challenge for me. He was open about it, but it was also hard drawing out the emotions from him so many decades after he had experienced it.

What did help was the fact that I found in my research process these letters that he had written to his older brother, Sam, who was living in America at the time. [These were] letters that he wrote in that late 1950s period, while he was still in the People’s Republic, but then also after he eventually fled to Hong Kong in the early ’60s, letters that expressed his feelings at the time. And so reading those letters gave me a much fuller sense of the depths of disappointment that he felt. I used the language from those letters [and] I think that really helped with those parts of the book.

Obviously language is a big part of it. If you can speak whatever language that your family member feels most comfortable talking, then that helps a lot. … The other thing I would say, if you’re trying to talk about your parents’ experiences during these very dramatic moments in history, even if they’re non-dramatic moments, is having a knowledge of that history is very helpful.

When I interviewed my dad in my 20s, I already had some of the foundation for that. … After working for almost a decade in China for The Times, and learning a lot more about China through my reporting, … when my father would talk about all these different beats in his life, different places he had gone, I could understand a lot more how it fit within the historical movements of the time.

I think that’s especially true of understanding his time in the army in Xinjiang in northwest China. It’s just an area that I had had very little contact with, a very low understanding of in my 20s. … I made my first trip there in ’99, and then when I moved to China for the New York Times, I went repeatedly to Xinjiang, both to report on stories but also, in a few instances, to try and trace my father’s footsteps in the region. … I think that seeing [the province] in person, and hearing stories about it from people on the ground there, it made a huge difference in terms of my ability to interview my father and get deeper into interviews with [him] once I moved back to the U.S.

One of the things that I’ve been very pleasantly surprised by is the amount of feedback I’ve gotten from Chinese American readers. Many of them have said that this book opened their eyes to the harrowing history that their parents or grandparents must have experienced. Many have also said, “Oh, this book inspires me to want to have much deeper conversations with more older people in my own family about their experiences in China before they immigrated to the U.S.” I think that for me, that’s very touching.

In some ways, I’m kind of surprised by that, because my book is, by far, not the first book to delve into a Chinese family’s history, including the history in the Mao era. There’s been other books that have done that, but I think it has been a while since there has been a book published using that as a narrative vehicle. And maybe it’s coming out at a moment when a lot of the discourse around China is often framed in geopolitical terms — a lot of it is about whether the U.S. and China will enter into a war in the near future, … whereas this book takes a very personal approach to China. I think it still tries to take a very clear-eyed approach, but at the same time is rooted in personal history. I think for many of these readers, that’s something that feels different than the current discourse on China.

I think that one of the hardest things to figure out when you’re in these world capitals, and you’re an official looking at the other one, is the intentions of the leadership in the capitals. And I think one thing that’s very concerning is if one government misreads the intentions of the other government or the other leadership. That’s how often war starts — with the misreading of intentions. And that could come from Beijing looking at Washington, or Washington looking at Beijing, and I think that’s something that people in my beat are constantly wondering about.

People in government, in the intelligence agencies, in the policy-making apparatus, are constantly wondering, “What are the intentions of a rival government’s leadership, and are we misreading those intentions? Are we reading them properly?” For example, probably the most salient example right now is the U.S. trying to look at Xi Jinping and wondering, “What are his intentions towards Taiwan?” And then on the flip side, officials in Beijing are looking at American leaders and wondering, “What are their intentions towards China’s relationship with Taiwan?” … So these efforts to read intentions are ongoing and intense, but if one side misreads the intentions of the other, then that could lead to disaster.

So what role can journalists play? I think journalists can use their reporting skills to look at what evidence there is out there on leaders’ intentions, and try and make that known publicly so that the discourse around it is grounded in some sort of contemporary evidence, rather than being purely hypothetical or theoretical or guesswork.