John Nery is associate editor of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the biggest newspaper in the Philippines. A staff member for more than 15 years, he writes opinion pieces and editorials. His analysis and reporting focus on politics, history, and the rule of law.

Nery was an organizer of the Democracy and Disinformation Forum held in the Philippines February 12-13. About 400 journalists, bloggers, scholars, students, advertising professionals, and PR practitioners discussed how to fight back against "fake news" and other forms of disinformation that threaten press freedoms.

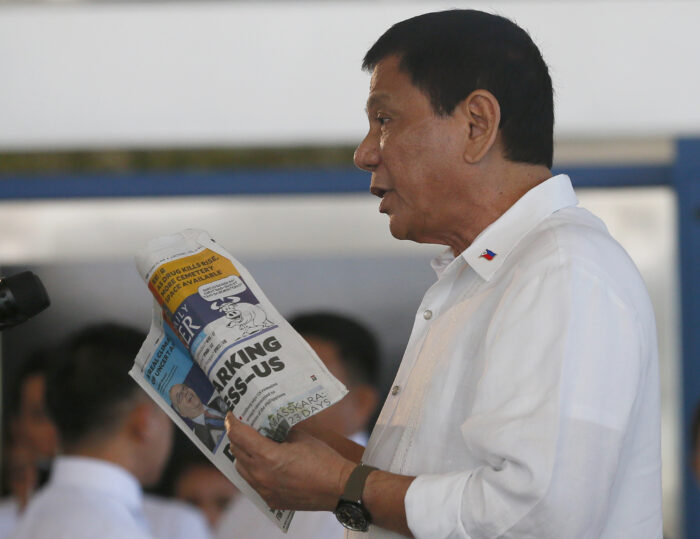

Earlier in the month Nery was in conversation at the Nieman Foundation with Glenda M. Gloria, managing editor and co-founder of Rappler, the leading social news network in the Philippines. President Duterte has accused Rappler of violating the constitutional Filipino ownership requirement and took the owners of the Inquirer to court over a disputed property. United Nations human rights experts have said that extrajudicial killings have increased in the Philippines since Duterte was elected in 2016. The Philippines, a founding member of the United Nations, dropped the most of any country in the 2017 Rule of Law Index, compiled by the World Justice Project, falling from 70 to 88. The United States dropped from 18 to 19.

Edited excerpts:

On social media as a state propaganda machine

Leaders like Hun Sen of Cambodia and Duterte of the Philippines have discovered the power that lies in social media. In May 2016, when Duterte had been elected as president, but he hadn’t yet taken his oath, his finance secretary Carlos Dominguez gave an interview in which he said, “Oh, we’re not going to disband our social media network. They will come in handy pushing our agenda.”

It started as a lark for some of these premiers and presidents to be on Facebook, to be on Instagram, but they’ve realized that while you can get immediate feedback, you can also push out messaging that you want people to receive immediately.

In the Philippines, they don’t call it a social media army. The digital campaign strategists for Duterte called it a “network of networks.” Some are volunteer groups supporting Duterte. They’ve put together a network of networks that had, for the first time in our history, the capacity to influence our election.

The Internet penetration rate in the Philippines is only about 50 percent, but even that 50 percent made an impact. What’s even more interesting is what happened after. Duterte came to power with only the second smallest mandate in our history, 38 percent, but his popularity ratings since then are in the stratosphere, the high 60s. That is partly because the rally-around-the flag effect was amplified by the network of networks.

I think the Duterte administration realizes that it’s only a matter of time before political gravity pulls his ratings down. That’s why they’re trying a crazy amount of things now, like trying to shut down Rappler, for instance, and trying to suspend a member of the independent graft‑busting agency when the Supreme Court itself said you cannot do that.

I think they know that they will really only have a window until the middle of next year, until the next elections. By then, people will be thinking about who’s going to be the next president.

On Duterte’s attacks on the press

He is criticizing journalists individually. In terms of trends, many of the death threats are received by journalists in the provinces, in the peripheries, not in the metropolitan area, not in metro Manila. We get libel suits. They get death threats. That’s a reflection of the power scale, even in Philippine journalism. Another trend is that women as a rule get more abuse and more kinds of abuse than male journalists. I’ve seen that with the reporters that I’ve had the privilege of working with.

Duterte has said that a free press is a privilege, not a right. That’s something very worrying. A free press is a right guaranteed by our own constitution.

Trump has popularized or weaponized the use of the phrase “fake news.” Even Duterte has now adopted that, calling Rappler “fake news.” It’s a new phrase in his language of intimidation.

On Duterte’s relationship with Trump and the U.S.

One of the most outrageous things Duterte said was a few months ago. “I think Donald Trump is misunderstood,” he said. “He’s actually a deep thinker.” I don’t know if he believes that or that’s just part of the games that presidents play, but Trump actually has a good relationship with Duterte, who has a deep‑seated anti‑Americanism. When he went on a state visit to China last October, he said, “I declare separation from the United States.” It was an astonishing thing because we have been independent since at least 1946.

Related Reading

“Unite and Resist Every and All Attempts to Silence Us”:

by Marites Vitug

What he meant was that number one, no more military exercises, but the military told Duterte that they need these military exercises with the United States. The United States, for once in our history, is working with a professional Philippine military. For many people, that’s the only thing standing between Duterte and an actual dictatorship. The military doesn’t want anything to do with the war on drugs. The military wants nothing to do with politics.

If you give Duterte enough time to appoint new generals, that’s going to change, but right now, and maybe for the next year or so, the current crop of generals just wants to do the job of soldiers, not politicians.

On China’s influence

The first important person that Duterte met after he was elected was the Chinese ambassador. They’ve been very close ever since.

The Philippines, two weeks into Duterte’s term, won a sweeping legal victory over China in the South China Sea. Duterte’s instructions were to give China “a soft landing.” I joined the view of other people who thought that it was a very Asian way of letting the Chinese save face. Don’t crow over the victory. Just give them a soft landing.

Unfortunately, the soft landing has turned into—to sustain the metaphor—a major beachhead. A couple of months ago, the president [decided] our two telcos are not doing a good enough job and they need a third player, and he wanted that player to be from China. The pivot to China has taken almost everyone by surprise. To be completely fair to him, I think he looks at the map and says it’s inevitable that China will dominate this part of the region of the world. We might as well ride the dragon’s back.

On opposing Duterte

There is a very real threat that the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague will at least investigate Duterte. I think the communication has already been filed with the International Criminal Court—I don't think the U.S. is a signatory—asking the ICC prosecutor to investigate the extrajudicial killings in the Philippines.

I’m very encouraged that when the remains of Marcos, the dictator, were allowed to be buried at our National Heroes’ Cemetery, there was an explosion of protests led by millennials. I keep telling the young people who I meet that when we were out in the streets in the 1980s protesting Marcos, not once did we think that our protests would actually work. He was so entrenched. The U.S. was behind him. There were U.S. bases in the Philippines at that time. The business committee was behind them. The Catholic Church was helping the opposition but at that point was very quiet. There was no way we thought it would work.

Duterte has a reputation for being a strategist. I don’t think so, but he is, in fact, a master tactician. Very, very good at doing something tomorrow that will undo the bad effects that happened today. That’s another reason why the opposition really can’t get its act together.

Unfortunately, for media to be viable it has to be owned by large corporations. That hasn’t been a hindrance to some of the great newspapers of the past as long as a measure of editorial independence is observed. It’s getting harder, especially in countries like ours, where institutions that should be sources of countervailing power are very weak.