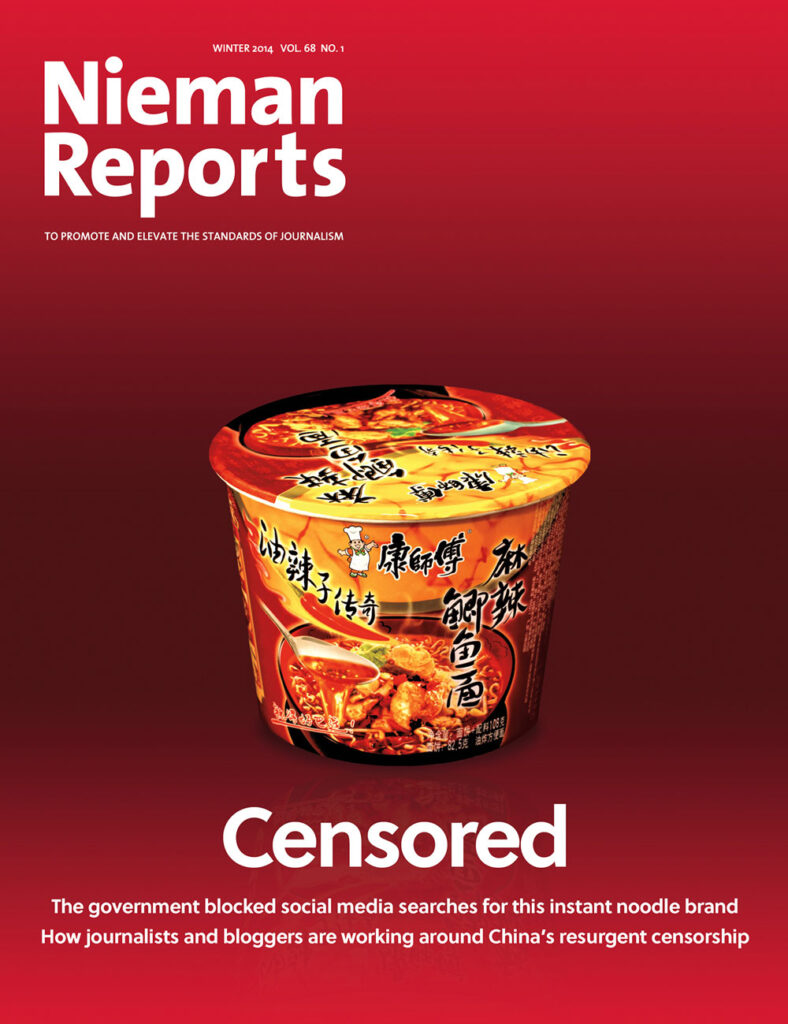

“The State of Journalism in China” looks at how journalists in China work around the Communist Party's efforts to rein in free speech. International reporters often face surveillance and harassment from the government, but in Paul Mooney's case, his visa renewal request was denied, effectively ending an 18-year career covering the country. Domestic journalists who operate under onerous censorship regulations have developed some creative ways to get around the rules, though these activities can become their own form of self-censorship, writes 2014 Nieman Fellow Yang Xiao. In some cases, those who run afoul of the government have been arrested and forced to confess to crimes on state-run television.

“The State of Journalism in China” looks at how journalists in China work around the Communist Party's efforts to rein in free speech. International reporters often face surveillance and harassment from the government, but in Paul Mooney's case, his visa renewal request was denied, effectively ending an 18-year career covering the country. Domestic journalists who operate under onerous censorship regulations have developed some creative ways to get around the rules, though these activities can become their own form of self-censorship, writes 2014 Nieman Fellow Yang Xiao. In some cases, those who run afoul of the government have been arrested and forced to confess to crimes on state-run television.Despite these conditions, reporters are still producing outstanding work in the country. David Barboza, Shanghai bureau chief for The New York Times, investigated the vast wealth accumulated by relatives of China's prime minister and won a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for his efforts. Reporters at the University of Hong Kong's China Media Project are mining the text of speeches and other propaganda to add context to contemporary news stories. As the world's second-largest economy and a booming global power, China is not going anywhere as a news story. Reporters, both domestic and international, will play a major role in what New Yorker staff writer Evan Osnos calls “an ongoing, unfinished debate about the definition of truth, accountability and power.”

This dual-language ebook has both English and Chinese versions of the text, and is available to download in epub and kindle formats:

A note about file types:

EPUB files can be opened in most eBook readers, like Apple's iBooks and Barnes & Noble's Nook. They can be read in a computer's browser using the Firefox add-on EPUBReader.

MOBI files can be read by popular eBook readers like the Amazon Kindle and many smartphones that support the format. Additionally, many eBook readers also have desktop software, mobile apps, and browser tools that allow the reading of MOBI files.