On a typical evening in the heart of Paris, Taha Siddiqui can be found at his bar, greeting customers and pouring drinks. During busy nights, he’s organizing events there, with an Afghan poet reading her work, anti-war Russian musicians in a punk band, or a director sharing their documentary — all, like him, finding refuge in France. But long before he became a bar owner, Siddiqui was one of Pakistan’s most high-profile investigative journalists, determined to expose corruption and government abuses. In 2018, after narrowly escaping a kidnapping and attempted assasination he believes was carried out by Pakistan’s army, he fled to Paris, where he has lived in exile ever since.

Siddiqui now channels his energy into the Dissident Club, a bar and community space he opened in 2020. Described as a “21st-century café littéraire,” it has become a bustling cultural hub for exiled journalists, whistleblowers, and dissidents from around the world; to date, dissenters from over 50 countries, including Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, Belarus, Mexico, Egypt, Russia, and China have visited or hosted events at the club. Activities include film screenings, book launches, poetry readings, art showings, comedy open mics, and panel discussions on human rights. The bar also hosts popular local jazz acts to help subsidize its programming.

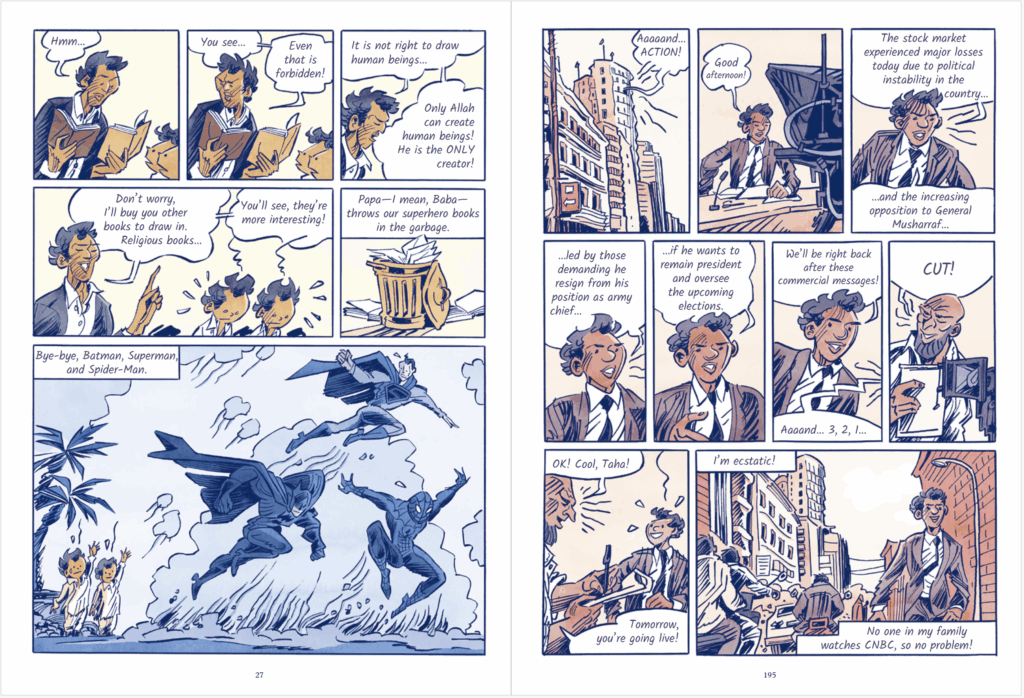

In addition to running the bar, Siddiqui continues to speak out on press freedom, Pakistani politics, and the challenges of living in exile. His recently published graphic memoir, “The Dissident Club,” recounts his journey from a strict Islamist upbringing in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan to his career as a journalist and the beginnings of his life in Paris. Curious and questioning as a child, Siddiqui often clashed with the dogma of his family’s fundamentalist beliefs — tensions that he says pushed him toward journalism as a way of interrogating authority and exposing abuses of power. Today, he provides political commentary for French media outlets and teaches journalism at various universities , all while curating a space for others who have also been forced to leave home.

For Siddiqui, the work is deeply personal. He sees the Dissident Club as a refuge where dissenters can find strength and solidarity with one another, countering the isolation often imposed on them through forced relocation in exile, the threat of surveillance, and transnational repression — all obstacles Siddiqui has had to face. This mission reflects his own trajectory: Pakistan remains one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, ranked 158th out of 180 in Reporters Without Borders’ 2025 Press Freedom Index, a drop of six places from last year.

Central to all these activities is Siddiqui’s refusal to be silenced or intimidated, and his belief that dissidents are ultimately safer when they band together. At the center of the Dissident Club stands a red pillar with a Leonardo da Vinci quote written in white paint: “Nothing strengthens authority so much as silence.”

Siddiqui spoke to Nieman Reports about his memoir, opening the Dissident Club, restarting his life in Paris, and how he keeps the bar running despite the challenges and pushback.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

When I arrived here in France in 2018, I was contacted by a few publishers, and they wanted me to do an autobiography because my case was well [known]. So I started shaping the first [draft] of the story and one of my friends went through it. He said, “Your story is really visual from what you want to tell. Have you ever thought of doing a comic book?”

That suggestion really stuck to me, because, when I was growing up, I didn’t have access to comic books. My parents, being religious and conservative Islamists, were not very fond of pictorial books of any kind. So I thought, if I do a book about my life, it should be a comic book, because in that way, it’s an act of resistance for me. I didn’t know anything about the world of comic books or graphic novels, but when I started looking into it, I saw that it has become a journalistic expression not only in France, but globally. France actually considers the form of “comic art” as the ninth form of art in the country. So I thought this would be the best way to tell my story.

When I started writing my story, I realized [my life path] had a lot to do with my childhood. People would ask me why I am the way that I am, because I come from a very different family, a very different social background, and a completely different cultural context, yet I’ve been able to transcend and break those barriers. I think telling the story of my childhood became a sort of a catharsis for myself, or an introspection into looking at how and why I became the person I am.

It was not one particular decision that made me open the Dissident Club. When I arrived here in France and I got my asylum status as a refugee, some of my journalistic contacts came up to me and said, “Listen, Taha, you had a good career in Pakistan as a journalist, we would just advise you to put that as a chapter of your life, and then you continue [on and] report on other things.” I started to see myself as an international reporter and doing international reporting elsewhere in the world in France or in Europe.

One thing that really bothered me in all of that was [the fact that] I am now a refugee. I do not have full citizenship, so I do not have the same rights as a citizen of France, for example, or any citizen of the world for that matter. I thought that I would be much more vulnerable than before, when I was at least a Pakistani citizen. I would not have the same protections, so I could not continue to do journalism [securely].

I didn’t want to quit journalism completely, and I wanted to do something connected to my career, experiences, and my need to exchange ideas with other people in a manner that is much safer. And I think in a bar, the only threat I have is from drunk people — although, I’ve had some issues [with] transnational repression.

The idea of a bar also came from this aspect: When I came into exile … I felt as if I did something wrong, and I was victim-blamed a lot because everybody said, “You could just shut up and live in Pakistan. Why did you have to do all of this, and put yourself in this trouble?” All my friends, my family, and journalists that I knew in Pakistan were all very negative about me taking this path, and so I felt really alone. Then I realized that, no, I’m not on my own. Actually, there are other people who are like me who have taken this decision of going into exile, and Paris is like a heaven for people in exile.

I thought a bar could be a very good way to connect with all these people under the same roof [and] showcase … we are still connected to our countries [and] even in exile, our work continues.

I’ve also used this opportunity to build a bridge between the Parisian, French society and exiled dissidents like me, because there is this negative image of a refugee as someone who has come seeking help and is totally dependent on the Western state. I wanted to show that this is not how it is. Some of us are willing to rebuild our lives and I wanted people, French people, to understand that I am willing to start all over again and do something with my life, even in exile.

I’ve been a big believer that the more visible [dissidents] are, the more [we] feel protected. If I am out there and very transparent, very open, I think that I have nothing to hide. A lot of people ask, “Why don’t you just stop doing what you’re doing?” And I say, “Shouldn’t the person who is threatening us stop threatening us?” At this point in my life, I consider [it to be] the responsibility of the French state and the French government to protect the people that it has vowed to protect, because I am under the French protection under [their] refugee laws. So I consider that Paris is a safe space for me, even though we have had cases of people being attacked in France.

I’ve had two or three [incidents of] surveillance, once or twice from the Pakistan Embassy [and] once from the Chinese Embassy. The most blatant out of them was the Chinese one, because the official parked his car right outside the bar, and I could see it was a diplomatic number plate. He walked in, had a beer at the bar, and then started talking to me. I asked, “You work for some embassy?” And he said, “Yeah, I work with the Chinese Embassy.” This was the week when we were doing this event about China, with dissidents from Hong Kong, from the Uyghur community, and from Tibet. I alerted [the dissidents], and I said, “There’s this guy coming here, and I think he’s looking for information.” So they stopped coming to the bar that week. Eventually, we published a story about this in a local newspaper saying that the Chinese Embassy was harassing us. I told him on his face that I don’t like to see him here, so he left.

Since I am in Paris, France, this provides me some protection; the fact that I’m very visible provides me some more protection. Yes, of course, transnational repression exists, it exists to stop people like us. But I left Pakistan to not stop. Now, I think that they should stop. And I point to anyone asking me why I don’t stop, or why I don’t have a low profile, I say, “This is my life. It’s my choice, and anyone who’s threatening this should reconsider their threats rather than me reconsidering any of my actions.”

As I mentioned earlier, the fact that I felt very alone when I came here and felt as if I did something wrong [or] stupid to go into exile. Why did I do this? Then I started meeting with these other exiled refugees, dissidents, artists, journalists, and academics — people from different walks of life. I met people from Russia, China, Afghanistan, and Iran. One thing I realized was that [we all have] similar sorts of stories. They were oppressed by judicial harassment, like myself, then were kidnapped or taken away to a secret prison. Then their work was censored in local media, or their social media activity was questioned and censored. I saw so many similarities, and I realized that all these authoritarian regimes have the same playbook when it comes to oppressing dissidents. That really motivated me to think that if [these countries] are collaborating, why should we as dissidents not do the same and get together?

Sometimes it really helps us. For example, some of the Tibetan Uyghur and Hong Kong activists didn’t know each other, but they came to the bar and they had some sort of common stories about how China oppresses all of them and how they fight back, and what methods they use. I think this kind of exchange of knowledge and experience is really important for dissidents in exile like us.

I think media organizations have their own limitations, but some media organizations use local journalists like me and then just discard them once our utility is done. I’ve seen that several times happening with friends from Pakistan who put their lives at risk for certain global Western media organizations and later on saw no support whatsoever when the time came to provide that kind of [help]. So I think these media organizations need to think a little bit more on that front.

But thankfully we have some other media organizations who do, as I mentioned. There are support organizations like Reporters Without Borders, Committee to Protect Journalists, Amnesty International, Free Press Unlimited, the European Union’s Human Rights Program. There is also the Front Line Defenders program. All of these organizations were really helpful for me in the beginning, in my first year here. They actually helped me financially and psychologically.

I had a lot of PTSD, so I went through therapy with the help of Reporters Without Borders. I went through trauma counseling to help adjust and start this new life here. I also got a relocation grant from the European Union’s Human Rights Defenders program. I think it’s not just about financial support at times, it’s also about psychological support.

Right now, I’m planning to launch the next phase of the Dissident Club. Basically, I would like to digitize all the activities we do, so [we can] reach beyond our walls, the physical space, and we are able to give virtual access to people.

We’re also collaborating with a radio channel here in Paris, and they want to do a live audience show from the bar, so we’re probably going to do that with them. I’m also thinking that I will do a show myself, like a weekly podcast from the Dissident Club, and I want to focus on dissidents … this idea of transnational repression, and how just because you go into exile doesn’t mean that now everything is OK. I want to bring in personalities from different parts of the world and show how, even in exile, life is still threatened, and there are still a lot of [ongoing] struggles.

This is why I run the Dissident Club: because of the people. One Iranian activist came by last week and said, “Hey, I’m sure you don’t remember, but today is my second year anniversary of being in Paris. If you remember the first night I was in Paris, I came to your bar, and I wanted to spend it with my friends here again,” and so he brought his friends. It just made me feel so good about what the Dissident Club has become today.