A longtime political consultant, David Axelrod has managed upwards of 150 local, state, and national campaigns—including Barack Obama’s 2008 and 2012 presidential runs, with a stint as the president’s senior advisor in between. But before he got his start in politics, Axelrod launched his career in journalism, joining the Chicago Tribune after graduating from the University of Chicago. There, he covered city hall and became a political columnist for the paper, where he worked for eight years before joining the campaign of Senator Paul Simon in 1984. Axelrod founded the Institute of Politics at the University of Chicago in 2013, and currently serves as its director. He is a senior political commentator on CNN, and hosts his own podcast, “The Axe Files.”

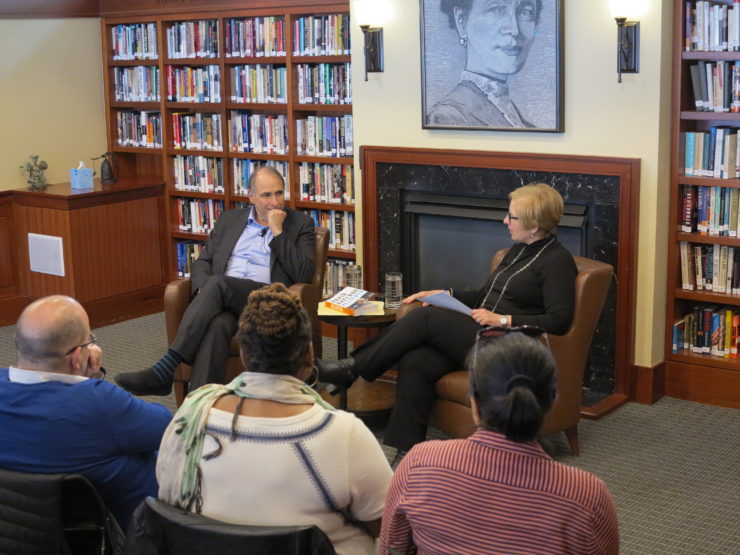

During a recent visit to the Nieman Foundation, Axelrod, in conversation with Nieman curator Ann Marie Lipinski, discussed polling, politicians shutting out reporters, and the value of storytelling in both journalism and politics. Edited excerpts:

When I set out to write my book, [“Believer: My Forty Years in Politics,”] I had no idea just how much of an exploration it was going to be, but when you write a memoir, you have to, if it’s going to be honest, dive into your own story, and you learn a lot about yourself.

One of the things I realized when I was writing this book was that I’m a storyteller. I’ve always been interested in other people’s stories, and one thing I enjoyed so much as a journalist was trying to get to those stories.

I’ve found that good journalism should always start with the assumption that there’s stuff you don’t know that you want to find out. When I met people, wherever I went, when I was covering politics around the country, for example, I just wanted to find out who these folks were and what was driving them and what they were thinking and what forces were at play.

Then, when I became a political strategist, I did message strategy, and I produced advertising, worked on speeches, and so on. That was another form of storytelling. Candidates need to tell an authentic story about who they are, about where they see their community, or their country, or the world going. The candidates who I prefer working with were people who also internalized the stories of people they met along the way.

I started working with Obama in 2002, when he was looking to run for the Senate. Every night, we’d talk. He’d be out on the road, and he’d share stories about people that he had met.

He’s a great practitioner of the narrative arts. You saw that in his own writing. But then, he would give political speeches, and they were very high‑level policy talks.

Finally, I said to him, “You know, every night, you tell me these moving stories. You should share those stories, because they animate the points you’re trying to make much more effectively.” He started integrating these stories into his speeches.

At the 2004 convention, when he got the assignment to do that speech, he said, “I stand here knowing my story is part of the larger American story.” Those were the exact words he used.

That’s what he did. He told his story, but he also told the story of people he met to animate what he stood for, and what he thought the Democratic Party should stand for.

For my podcast, I’m interested in people’s stories. I think one of the things that would take the heat out of our politics would be if we knew each other better. We live in such siloed worlds. We have predispositions about people in politics. If they are a Republican, they’re one way. If they are Democrat, they’re another. I’m interested in who they are as human beings.

We can still disagree, but I think you’ll find that when you hear people’s stories, there is a common humanity that is healthy and important. Everybody has got a story. We ought to try and find out what our respective stories are.

My mother was a journalist. She was one of the first women working on a city desk in New York, in the ’40s. Then, she was a freelancer. Ultimately, she ended up in advertising, doing qualitative research, focus groups. I grew up around all of this.

She said she was able to make that transition, because if you do qualitative research properly, there’s neutrality to the moderator. You’re not there to be judgmental. You’re not there to impose your view on the people in front of you. You’re there to elicit from them what they’re thinking, and what they’re feeling. That’s what reporters should be doing as well. Just as if you were in a focus group, I don’t think you want to talk to people you’re interviewing and present them with leading questions, and give them cues as to how you want them to answer. I think you want to find out who they are and what their story is and what motivates them.

I do think that how you present yourself is important. The best reporters that I’ve known are reporters who are intellectually curious, and they know the right questions to ask but they never presume what the answer is going to be, because people are counterintuitive and they can surprise you. Of course, one of the joys of doing the work is to be surprised and to learn something that you didn’t know before.

The nature of cable television is you have to fill a lot of time. That’s part of what’s going on. That’s not just common to CNN, but I will say this: During the election, I was on these big panels on election nights and debate nights and so on. Everybody said it’s unwieldy. How can you sit there with Jeffrey Lord or whoever was representing Trump? I think back at it. I was there more as an analyst than a surrogate, which was my deal.

When all of the really smart people in politics were saying, “We’re dismissing Trump,” Jeffrey Lord was saying, “You know what? Back where I’m from, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where I live, they’re talking about different stuff.” He was well ahead of everybody on what was going on out there.

I learned a little humility from that, because there were times when I was dismissive of what he was saying. It turned out that he was right about some of what he was saying. I find some of the debate shouting and back‑and‑forth completely unproductive at times. At other times, though, it’s playing out arguments that are going on in our country. I’m less judgmental about it.

Cable television is 24 hours, seven days a week. Everything is breaking news, because you’re competing for eyeballs. Sometimes, creating that tension is part of trying to draw eyeballs. At times, that can unearth things that are valuable. At times, it can make you want to jump out the window.

Dan [Balz of The Washington Post], to me, is the gold standard for political reporting, because he is really thoughtful. He was trained up by David Broder, another legendary journalist.

These were the guys who I watched when I was coming up, who would go out and knock on doors. They’d get in a car and they’d drive across state. Their newspapers would subsidize that. They weren't filing every hour. They had time to do the work.

David Maraniss, who is another one of that group from the Post, told me a story about David Broder and Balz. They were sitting around in The Washington Post lunchroom or whatever, after one of the presidential elections. It was February, a few weeks after a new president took office. Broder said to them, “I just feel like jumping in a car and going up to Manchester and knocking on doors, don’t you?”

I applaud that. There are still people who do that—Dan is one of them—but the pace of journalism has changed and the resources that are there don’t allow for that as much.

If I were in my dream world and I were an editor, I would say to my political writers, “Go out into the country and find good stories. You don’t have to file every day, but find out what’s going on out there.”

Polling has become a crutch—a crutch for journalists, perhaps a crutch for candidates as well. Polling allows political reporting on the cheap. It allows news organizations to brand a poll and get some attention.

We are far too reliant on these polls. Many of them are not right. Some of them are. There’s a mythology that the polls were all wrong in 2016. If you aggregated the public polls, it would have said that Hillary Clinton was going to carry the country by two to four percent, and she did. The polls drive conventional thinking. They’re uneven in quality. Some news organizations pour a lot of money [into polling and they’re] well‑resourced, done by really good pollsters. There are other polling operations that aren’t as good, but they all get treated the same way.

I used to fight the polling battle every day in 2012 because some polls would have us up by eight, which we never were, or down by eight, which we never were. There was one day where one poll had us beating Mitt Romney by 12 points nationally, and another poll had us down by six. Both can’t be true, and yet, each one of them gets treated like they’re the same thing.

If I had my druthers, I would ban polling. You can’t do that, obviously, but it would be better to get back in the car and go out there and ask people questions and get a feel for what’s going on in the country. They’re a pernicious force. Polling has become a crutch that absolves a bunch of folks from doing the hard work of reporting and trying to figure out what’s going on.

One of my roles with candidates, because I did spend so much of my formative life in journalism, was to explain what the role of a journalist was and to urge them not to view every journalist as a malign force and to understand that there was a certain obligation to communicate with the public through [the media].

The thing that’s changed is that there are [now] ways to talk around journalists. There are more direct ways—like Donald Trump obviously has found Twitter to be a useful tool to talk over and around journalists. Now, people are covering his tweets rather than press conferences which he does relatively rarely. There are more tools now for people to communicate.

I think that officeholders like Obama’s people frustrated the White House press corps because they would do nontraditional interviews, [like] go do Marc Maron’s podcast or “Between Two Ferns”—a whole bunch of different things because it was a way to reach different constituencies. It was a way to get a longer-form place to talk. They did a lot of stuff with local news or outlets because they had a certain audience that they wanted to reach, and this frustrated the White House press corps.

I think officeholders have to communicate in the way that they think is most effective. I don’t think it’s a good idea in a fit of pique to say, “I'm not going to talk to the media because I don’t like the way I'm being covered.”

During a recent visit to the Nieman Foundation, Axelrod, in conversation with Nieman curator Ann Marie Lipinski, discussed polling, politicians shutting out reporters, and the value of storytelling in both journalism and politics. Edited excerpts:

On the value of storytelling in journalism and in politics

When I set out to write my book, [“Believer: My Forty Years in Politics,”] I had no idea just how much of an exploration it was going to be, but when you write a memoir, you have to, if it’s going to be honest, dive into your own story, and you learn a lot about yourself.

One of the things I realized when I was writing this book was that I’m a storyteller. I’ve always been interested in other people’s stories, and one thing I enjoyed so much as a journalist was trying to get to those stories.

I’ve found that good journalism should always start with the assumption that there’s stuff you don’t know that you want to find out. When I met people, wherever I went, when I was covering politics around the country, for example, I just wanted to find out who these folks were and what was driving them and what they were thinking and what forces were at play.

Then, when I became a political strategist, I did message strategy, and I produced advertising, worked on speeches, and so on. That was another form of storytelling. Candidates need to tell an authentic story about who they are, about where they see their community, or their country, or the world going. The candidates who I prefer working with were people who also internalized the stories of people they met along the way.

I started working with Obama in 2002, when he was looking to run for the Senate. Every night, we’d talk. He’d be out on the road, and he’d share stories about people that he had met.

He’s a great practitioner of the narrative arts. You saw that in his own writing. But then, he would give political speeches, and they were very high‑level policy talks.

Finally, I said to him, “You know, every night, you tell me these moving stories. You should share those stories, because they animate the points you’re trying to make much more effectively.” He started integrating these stories into his speeches.

At the 2004 convention, when he got the assignment to do that speech, he said, “I stand here knowing my story is part of the larger American story.” Those were the exact words he used.

That’s what he did. He told his story, but he also told the story of people he met to animate what he stood for, and what he thought the Democratic Party should stand for.

For my podcast, I’m interested in people’s stories. I think one of the things that would take the heat out of our politics would be if we knew each other better. We live in such siloed worlds. We have predispositions about people in politics. If they are a Republican, they’re one way. If they are Democrat, they’re another. I’m interested in who they are as human beings.

We can still disagree, but I think you’ll find that when you hear people’s stories, there is a common humanity that is healthy and important. Everybody has got a story. We ought to try and find out what our respective stories are.

On what his mother taught him about how journalists should present themselves

My mother was a journalist. She was one of the first women working on a city desk in New York, in the ’40s. Then, she was a freelancer. Ultimately, she ended up in advertising, doing qualitative research, focus groups. I grew up around all of this.

She said she was able to make that transition, because if you do qualitative research properly, there’s neutrality to the moderator. You’re not there to be judgmental. You’re not there to impose your view on the people in front of you. You’re there to elicit from them what they’re thinking, and what they’re feeling. That’s what reporters should be doing as well. Just as if you were in a focus group, I don’t think you want to talk to people you’re interviewing and present them with leading questions, and give them cues as to how you want them to answer. I think you want to find out who they are and what their story is and what motivates them.

I do think that how you present yourself is important. The best reporters that I’ve known are reporters who are intellectually curious, and they know the right questions to ask but they never presume what the answer is going to be, because people are counterintuitive and they can surprise you. Of course, one of the joys of doing the work is to be surprised and to learn something that you didn’t know before.

On punditry at CNN

The nature of cable television is you have to fill a lot of time. That’s part of what’s going on. That’s not just common to CNN, but I will say this: During the election, I was on these big panels on election nights and debate nights and so on. Everybody said it’s unwieldy. How can you sit there with Jeffrey Lord or whoever was representing Trump? I think back at it. I was there more as an analyst than a surrogate, which was my deal.

When all of the really smart people in politics were saying, “We’re dismissing Trump,” Jeffrey Lord was saying, “You know what? Back where I’m from, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where I live, they’re talking about different stuff.” He was well ahead of everybody on what was going on out there.

I learned a little humility from that, because there were times when I was dismissive of what he was saying. It turned out that he was right about some of what he was saying. I find some of the debate shouting and back‑and‑forth completely unproductive at times. At other times, though, it’s playing out arguments that are going on in our country. I’m less judgmental about it.

Cable television is 24 hours, seven days a week. Everything is breaking news, because you’re competing for eyeballs. Sometimes, creating that tension is part of trying to draw eyeballs. At times, that can unearth things that are valuable. At times, it can make you want to jump out the window.

On great political reporting

Dan [Balz of The Washington Post], to me, is the gold standard for political reporting, because he is really thoughtful. He was trained up by David Broder, another legendary journalist.

These were the guys who I watched when I was coming up, who would go out and knock on doors. They’d get in a car and they’d drive across state. Their newspapers would subsidize that. They weren't filing every hour. They had time to do the work.

David Maraniss, who is another one of that group from the Post, told me a story about David Broder and Balz. They were sitting around in The Washington Post lunchroom or whatever, after one of the presidential elections. It was February, a few weeks after a new president took office. Broder said to them, “I just feel like jumping in a car and going up to Manchester and knocking on doors, don’t you?”

I applaud that. There are still people who do that—Dan is one of them—but the pace of journalism has changed and the resources that are there don’t allow for that as much.

If I were in my dream world and I were an editor, I would say to my political writers, “Go out into the country and find good stories. You don’t have to file every day, but find out what’s going on out there.”

On polling

Polling has become a crutch—a crutch for journalists, perhaps a crutch for candidates as well. Polling allows political reporting on the cheap. It allows news organizations to brand a poll and get some attention.

We are far too reliant on these polls. Many of them are not right. Some of them are. There’s a mythology that the polls were all wrong in 2016. If you aggregated the public polls, it would have said that Hillary Clinton was going to carry the country by two to four percent, and she did. The polls drive conventional thinking. They’re uneven in quality. Some news organizations pour a lot of money [into polling and they’re] well‑resourced, done by really good pollsters. There are other polling operations that aren’t as good, but they all get treated the same way.

I used to fight the polling battle every day in 2012 because some polls would have us up by eight, which we never were, or down by eight, which we never were. There was one day where one poll had us beating Mitt Romney by 12 points nationally, and another poll had us down by six. Both can’t be true, and yet, each one of them gets treated like they’re the same thing.

If I had my druthers, I would ban polling. You can’t do that, obviously, but it would be better to get back in the car and go out there and ask people questions and get a feel for what’s going on in the country. They’re a pernicious force. Polling has become a crutch that absolves a bunch of folks from doing the hard work of reporting and trying to figure out what’s going on.

On politicians getting their message out

One of my roles with candidates, because I did spend so much of my formative life in journalism, was to explain what the role of a journalist was and to urge them not to view every journalist as a malign force and to understand that there was a certain obligation to communicate with the public through [the media].

The thing that’s changed is that there are [now] ways to talk around journalists. There are more direct ways—like Donald Trump obviously has found Twitter to be a useful tool to talk over and around journalists. Now, people are covering his tweets rather than press conferences which he does relatively rarely. There are more tools now for people to communicate.

I think that officeholders like Obama’s people frustrated the White House press corps because they would do nontraditional interviews, [like] go do Marc Maron’s podcast or “Between Two Ferns”—a whole bunch of different things because it was a way to reach different constituencies. It was a way to get a longer-form place to talk. They did a lot of stuff with local news or outlets because they had a certain audience that they wanted to reach, and this frustrated the White House press corps.

I think officeholders have to communicate in the way that they think is most effective. I don’t think it’s a good idea in a fit of pique to say, “I'm not going to talk to the media because I don’t like the way I'm being covered.”