Almost 50 years after Nat Nakasa, NF ’65, died and was buried

in a New York cemetery,

his remains have been brought back to South Africa. The repatriation fulfills not only Nat’s dream but the

wish of a great many South African journalists.

Nat’s return is a collective effort at closure, giving him what we all believe he would have wanted and which the cruel system of apartheid had denied him. It is a restoration of his humanity. It is also a reaffirmation that as a nation and as a community of journalists we will go to the end of the world to bring our own back. It allows us to exhale knowing that this one was done properly.

Nat believed in freedom. He also believed in quality journalism that would serve society. That is why he resisted restrictions on where he would live or what he could or could not write. He was courageous and principled.

So when an opportunity came for him to broaden his horizons through a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard in 1964, he grabbed it with both hands. The price, however, was huge. The apartheid regime said he had to forsake his home country and become stateless, a wanderer, as he himself put it.

He made that difficult decision because in that departure Nat saw the possibility of serving South Africa better. But he also hoped to come back. That was not to be. Lonely and homesick, he fell from a high-rise building in New York in mysterious circumstances and died on July 14, 1965, aged 28.

Nat was buried at the New York cemetery where Malik el Shabazz, otherwise famously known as Malcolm X, was buried. The two had met in Dar es Salaam. Nat was waiting for a Tanzanian passport that would allow him to enter the United States for his Nieman Fellowship, and Malik was on his tour of rediscovery through Africa.

In recognition of Nat’s contribution to journalism and what he stood for, the Nieman Society of Southern Africa, the South African National Editors Forum (Sanef), and the Print and Digital Media of South Africa (PDMSA) established South African journalism’s highest honor, the Nat Nakasa Award for Courageous Journalism, which is awarded annually to a media practitioner such as a journalist, editor, manager, or owner who has shown integrity, reported fearlessly, and displayed a commitment to serve the people of South Africa.

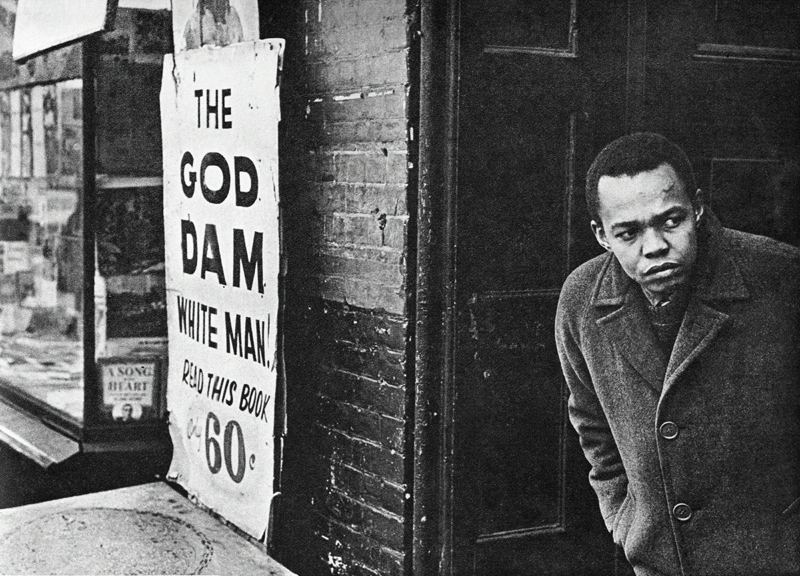

Nat was no firebrand revolutionary. Instead, he looked for possibilities of rapproachment between the different races. He was however defiant, and refused to live in the segregated township designated for blacks, choosing instead to slum it in town.

He was a ferocious reader and able writer who used his pen to demonstrate, in easy language, the absurdity of apartheid. His legacy for South African journalism is a commitment to the highest ideals of journalism, truth at whatever cost.

The Nieman Society, Sanef, the South African government, and a host of individuals have worked tirelessly to navigate the labyrinth of U.S. laws relating to the exhumation and repatriation of remains. In June, a New York court granted permission, and Nat’s wish to return to mother Africa was finally fulfilled in late August.

Nat’s return is a collective effort at closure, giving him what we all believe he would have wanted and which the cruel system of apartheid had denied him. It is a restoration of his humanity. It is also a reaffirmation that as a nation and as a community of journalists we will go to the end of the world to bring our own back. It allows us to exhale knowing that this one was done properly.

Nat believed in freedom. He also believed in quality journalism that would serve society. That is why he resisted restrictions on where he would live or what he could or could not write. He was courageous and principled.

So when an opportunity came for him to broaden his horizons through a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard in 1964, he grabbed it with both hands. The price, however, was huge. The apartheid regime said he had to forsake his home country and become stateless, a wanderer, as he himself put it.

He made that difficult decision because in that departure Nat saw the possibility of serving South Africa better. But he also hoped to come back. That was not to be. Lonely and homesick, he fell from a high-rise building in New York in mysterious circumstances and died on July 14, 1965, aged 28.

Nat was buried at the New York cemetery where Malik el Shabazz, otherwise famously known as Malcolm X, was buried. The two had met in Dar es Salaam. Nat was waiting for a Tanzanian passport that would allow him to enter the United States for his Nieman Fellowship, and Malik was on his tour of rediscovery through Africa.

In recognition of Nat’s contribution to journalism and what he stood for, the Nieman Society of Southern Africa, the South African National Editors Forum (Sanef), and the Print and Digital Media of South Africa (PDMSA) established South African journalism’s highest honor, the Nat Nakasa Award for Courageous Journalism, which is awarded annually to a media practitioner such as a journalist, editor, manager, or owner who has shown integrity, reported fearlessly, and displayed a commitment to serve the people of South Africa.

Nat was no firebrand revolutionary. Instead, he looked for possibilities of rapproachment between the different races. He was however defiant, and refused to live in the segregated township designated for blacks, choosing instead to slum it in town.

He was a ferocious reader and able writer who used his pen to demonstrate, in easy language, the absurdity of apartheid. His legacy for South African journalism is a commitment to the highest ideals of journalism, truth at whatever cost.

The Nieman Society, Sanef, the South African government, and a host of individuals have worked tirelessly to navigate the labyrinth of U.S. laws relating to the exhumation and repatriation of remains. In June, a New York court granted permission, and Nat’s wish to return to mother Africa was finally fulfilled in late August.