In April 2007, the Pulitzer Prize Board gave its award in editorial writing to Arthur Browne, Beverly Weintraub, and Heidi Evans of the New York Daily News "for their compassionate and compelling editorials on behalf of Ground Zero workers whose health problems were neglected by the city and the nation." In the article that follows, two of those writers describe what they learned about how a newspaper's editorial page can mesh investigative reporting with a strong editorial voice to bring the necessary scrutiny to a matter of public health.

It began with the death of a New York City cop. On January 5, 2006, New York Police Department (NYPD) Homicide Detective James Zadroga, who had worked 450 hours at the World Trade Center site following the September 11th terrorist attack, died at age 34 of lung disease. His parents blamed his death on exposure to airborne poisons at Ground Zero's infamous pile.

Like many in the city's press, the Daily News editorial board had heard stories like this before, of first responders sickened or dead after working at Ground Zero. Their families were convinced World Trade Center (WTC) toxins were to blame, and some medical experts agreed. Yet public officials were noncommittal or dismissive of any cause and effect.

In an editorial titled "Ground Zero Deaths Need Investigating," published January 22, 2006, the News noted that a lawyer named David Worby — looking to file a class-action suit on behalf of 5,000 people exposed to the WTC site — claimed to know of 23 rescue and recovery workers who had died as a direct result of exposure at Ground Zero. But because no one — not the federal government nor state nor city health officials — had done a systematic analysis of potential WTC-related illnesses and deaths, it was impossible to know whether Worby's claim was credible.

"Now is the time," the Daily News wrote in this editorial, "to begin a search for definitive answers — both to complete the historical record of 9/11 and, more importantly, to give a straight story to all those who are worried about their futures." A follow-up editorial February 19, 2006, titled "Clear the Air on 9/11 Health," described the fear and confusion gripping thousands of sick rescue and recovery workers.

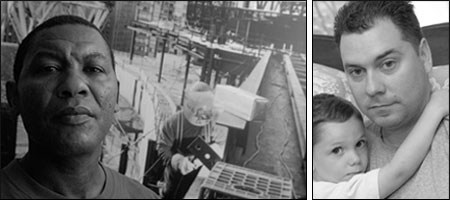

Far left, first responder, firefighter Stephen M. Johnson, before 9/11. Johnson died on August 6, 2004. Photo by Susana Bates, Freelance/New York Daily News. Right, Mark DeBiase and his wife, Jeanmarie, in the hospital before he died. 2006. Photo by Jim Hughes.

Acquiring Authority to Speak

It quickly became apparent that no public officials were willing to take on this crucial issue. Thousands of brave Americans had responded to the most devastating and toxic attack on the United States. But the government was silent. So the New York Daily News editorial page decided to tackle it.

From February through May 2006, an editorial board member (Bev Weintraub) read two dozen peer-reviewed medical journals and interviewed scientists. Using that data, timelines were sketched of what substances were in the air, when they were considered to be most toxic, and what effects each had on the human body at different points in time — on the day of exposure, a week later, months later, years later. While a wealth of information was available, none of it had ever been presented to the public in a coherent form.

Experts in environmental health had published no fewer than 27 medical journal articles documenting what happened to different populations of first responders at various times. By interviewing administrators of WTC treatment programs, the board calculated for the first time — very conservative estimates, it turned out — how many responders had worked at Ground Zero (40,000) and how many were sick — 12,000. This by itself was big news.

The editorial board also documented the tremendous difficulties many responders were having in receiving benefits for medical treatment — or in getting treatment at all. And it found some disturbing parallels in the deaths of three rescue workers felled by unusual lung-scarring diseases in the prime of their lives.

Daily News Editorial Page Editor Arthur Browne realized the story was much bigger than many of the subjects the editorial page typically took on. There was also a very large gap between what the newspaper was discovering and what the public knew. "The editorial page normally comments on events and information that are out there for general discussion. And maybe on this page, a reader will find out some facts that will advance the argument that the board wants to make. But it's generally not of a big, sweeping, overarching issue that involves thousands of people," said Browne.

By May, it became clear that the editorial board could advocate for changes by presenting the facts in a fresh, in-depth way and by speaking with scientific-based authority.

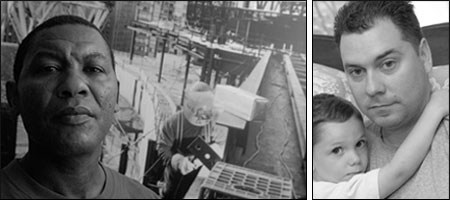

First responder Winston Lodge, left, an ironworker, suffers from many respiratory and sinus problems. This photo was taken in his home in front of a photograph of him working at Columbus Circle. Photo by Susana Bates, Freelance/New York Daily News. Christopher Hynes, far right, a 35-year-old New York City Police Officer of the 43rd Precinct in the Bronx, is on restricted duty because of sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and asthma, all effects of his work during the 9/11 attacks. He is pictured with his 4-year-old son. July 2007. Photo by Enid Alvarez/New York Daily News.

Meshing Reporting With Advocacy

Browne alerted the editor of the paper that a major project was in the works, one that could go far beyond a typical editorial campaign. Editor in Chief Martin Dunn loaned the editorial board a reporter (Heidi Evans), who'd covered health issues for years, including the medical and psychological effects of the terrorist attacks in the days and years after September 11th. To round out the project, dozens of ailing responders and volunteers in the New York area and around the country were interviewed. Some of the interviews were done in person, as with lung-scarred volunteer Vito Valenti at his home on Long Island.

The first-person stories of the people — with their photographs, which were published on the front page of the newspaper — were very powerful. Readers saw the people who had died, and the people who were dying, and the words of the people who were sick. It was all real and in context.

"This could have been written as a straight-ahead investigative project on the news side, but I don't think it would have had the impact," said Browne. "However powerful, the information would have been presented in a completely neutral way, and the findings could not have been wrapped into a call for action as could happen on the editorial page."

Moreover, he added, "opinion journalism is changing a great deal because now everyone has an opinion and everyone has an instant opinion. Everyone can blog and tune into TV for 24/7 news analysis. Editorial pages should strive to do more than comment on the things that are out there. They should try to add value to the discussion. Each paper's editorial page needs to come to a recognition of what it stands for in terms of advancing the interests of its readers and how it perceives the best ways to do it.

"To my mind, it clearly is not simply to look at the top five stories in the paper and offer an opinion about them. You have to re-report on your own for the editorial page, and you need to find new information about a story. Editorials should bring a new perspective. People should learn something more than what you think about it. They should learn why you think it. And if you could add value to it, that's a good thing."

James Nolan, left, 41, a local 608 carpenter and first responder on 9/11, suffers from upper and lower pulmonary infection, an enlarged liver, rash on his hands, high blood pressure, and a compromised immune system. He spent two and a half years working at Ground Zero. Photo by Enid Alvarez/New York Daily News. Vito J. Valenti, far right, is on many medications and has to breathe oxygen due to lung problems he developed after working on the 9/11 site. His father, Joseph, left, has moved in to help care for him. 2006. Photo by Frank Koester.

Public Service Journalism

The series did just that, drawing on interviews with doctors who ran 9/11 clinics, experts in pulmonary disease, federal, state and city officials, members of the health, police and fire departments and their unions. The Daily News also interviewed Workers' Compensation Board members and lawyers, members of Congress, including Senator Hillary Clinton and Representative Carolyn Maloney, mayoral and gubernatorial aides, responders' survivors and their attorneys, and dozens of firefighters, police officers, construction workers, and cleanup volunteers. The team also combed through Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) documents, questionable statements to the public from then-EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman and then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani, and transcripts of congressional debates that found surprising precedents in issues of workers' compensation for civilians that arose after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Beginning July 23, 2006, almost five years after the WTC fell, the Daily News published the opening editorial in a campaign titled "9/11: The Forgotten Victims — A Call to Action." The paper's editorial board produced 13 prominent editorials in 2007, including some featured on the front page, and the Daily News supplemented the series with editorial cartoons and letters to the editor.

By marshaling the facts in a way no one had done before, the Daily News editorial page built an unimpeachable case that the illnesses were real and presented harsh indictments of public officials who denied care to rescue and recovery workers. Most importantly, the Daily News demanded — and got — action. After years of studied ignorance, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released $75 million — the first federal aid — dedicated to treating 9/11 responders. The state eased workers' compensation rules; the city began funding treatment programs. And the newspaper, through its editorials, provided much-needed facts to stricken responders.

In retrospect, it is startling to consider how little was known about the epidemic of lung diseases afflicting 9/11 workers before the series ran. In the 58 months after 9/11, New York City's five general-interest newspapers — including The New York Times — never once printed the term "reactive airways distress syndrome," although the asthma-like condition was growing into a prevalent debilitating ailment among responders. Now the diseases suffered by the rescue and recovery workers — and their sometimes fatal consequences — are accepted fact.

Given the hard times newspapers find themselves in, now more than ever investigative reporting and public interest journalism should be encouraged and applauded no matter where it appears — including on the editorial pages. By marrying reportorial resources with an editorial board's ability to take sides on important issues and prescribe remedies, the Daily News produced a groundbreaking series that got help for thousands of people. We hope other newspapers will find inspiration in this example.

Heidi Evans, a 1993 Nieman Fellow, is a staff writer for the Daily News. Beverly Weintraub is a member of that newspaper's editorial board. To read the editorials, go to www.pulitzer.org, and click on 2007 winners, editorial writing.

It began with the death of a New York City cop. On January 5, 2006, New York Police Department (NYPD) Homicide Detective James Zadroga, who had worked 450 hours at the World Trade Center site following the September 11th terrorist attack, died at age 34 of lung disease. His parents blamed his death on exposure to airborne poisons at Ground Zero's infamous pile.

Like many in the city's press, the Daily News editorial board had heard stories like this before, of first responders sickened or dead after working at Ground Zero. Their families were convinced World Trade Center (WTC) toxins were to blame, and some medical experts agreed. Yet public officials were noncommittal or dismissive of any cause and effect.

In an editorial titled "Ground Zero Deaths Need Investigating," published January 22, 2006, the News noted that a lawyer named David Worby — looking to file a class-action suit on behalf of 5,000 people exposed to the WTC site — claimed to know of 23 rescue and recovery workers who had died as a direct result of exposure at Ground Zero. But because no one — not the federal government nor state nor city health officials — had done a systematic analysis of potential WTC-related illnesses and deaths, it was impossible to know whether Worby's claim was credible.

"Now is the time," the Daily News wrote in this editorial, "to begin a search for definitive answers — both to complete the historical record of 9/11 and, more importantly, to give a straight story to all those who are worried about their futures." A follow-up editorial February 19, 2006, titled "Clear the Air on 9/11 Health," described the fear and confusion gripping thousands of sick rescue and recovery workers.

Far left, first responder, firefighter Stephen M. Johnson, before 9/11. Johnson died on August 6, 2004. Photo by Susana Bates, Freelance/New York Daily News. Right, Mark DeBiase and his wife, Jeanmarie, in the hospital before he died. 2006. Photo by Jim Hughes.

Acquiring Authority to Speak

It quickly became apparent that no public officials were willing to take on this crucial issue. Thousands of brave Americans had responded to the most devastating and toxic attack on the United States. But the government was silent. So the New York Daily News editorial page decided to tackle it.

From February through May 2006, an editorial board member (Bev Weintraub) read two dozen peer-reviewed medical journals and interviewed scientists. Using that data, timelines were sketched of what substances were in the air, when they were considered to be most toxic, and what effects each had on the human body at different points in time — on the day of exposure, a week later, months later, years later. While a wealth of information was available, none of it had ever been presented to the public in a coherent form.

Experts in environmental health had published no fewer than 27 medical journal articles documenting what happened to different populations of first responders at various times. By interviewing administrators of WTC treatment programs, the board calculated for the first time — very conservative estimates, it turned out — how many responders had worked at Ground Zero (40,000) and how many were sick — 12,000. This by itself was big news.

The editorial board also documented the tremendous difficulties many responders were having in receiving benefits for medical treatment — or in getting treatment at all. And it found some disturbing parallels in the deaths of three rescue workers felled by unusual lung-scarring diseases in the prime of their lives.

Daily News Editorial Page Editor Arthur Browne realized the story was much bigger than many of the subjects the editorial page typically took on. There was also a very large gap between what the newspaper was discovering and what the public knew. "The editorial page normally comments on events and information that are out there for general discussion. And maybe on this page, a reader will find out some facts that will advance the argument that the board wants to make. But it's generally not of a big, sweeping, overarching issue that involves thousands of people," said Browne.

By May, it became clear that the editorial board could advocate for changes by presenting the facts in a fresh, in-depth way and by speaking with scientific-based authority.

First responder Winston Lodge, left, an ironworker, suffers from many respiratory and sinus problems. This photo was taken in his home in front of a photograph of him working at Columbus Circle. Photo by Susana Bates, Freelance/New York Daily News. Christopher Hynes, far right, a 35-year-old New York City Police Officer of the 43rd Precinct in the Bronx, is on restricted duty because of sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and asthma, all effects of his work during the 9/11 attacks. He is pictured with his 4-year-old son. July 2007. Photo by Enid Alvarez/New York Daily News.

Meshing Reporting With Advocacy

Browne alerted the editor of the paper that a major project was in the works, one that could go far beyond a typical editorial campaign. Editor in Chief Martin Dunn loaned the editorial board a reporter (Heidi Evans), who'd covered health issues for years, including the medical and psychological effects of the terrorist attacks in the days and years after September 11th. To round out the project, dozens of ailing responders and volunteers in the New York area and around the country were interviewed. Some of the interviews were done in person, as with lung-scarred volunteer Vito Valenti at his home on Long Island.

The first-person stories of the people — with their photographs, which were published on the front page of the newspaper — were very powerful. Readers saw the people who had died, and the people who were dying, and the words of the people who were sick. It was all real and in context.

"This could have been written as a straight-ahead investigative project on the news side, but I don't think it would have had the impact," said Browne. "However powerful, the information would have been presented in a completely neutral way, and the findings could not have been wrapped into a call for action as could happen on the editorial page."

Moreover, he added, "opinion journalism is changing a great deal because now everyone has an opinion and everyone has an instant opinion. Everyone can blog and tune into TV for 24/7 news analysis. Editorial pages should strive to do more than comment on the things that are out there. They should try to add value to the discussion. Each paper's editorial page needs to come to a recognition of what it stands for in terms of advancing the interests of its readers and how it perceives the best ways to do it.

"To my mind, it clearly is not simply to look at the top five stories in the paper and offer an opinion about them. You have to re-report on your own for the editorial page, and you need to find new information about a story. Editorials should bring a new perspective. People should learn something more than what you think about it. They should learn why you think it. And if you could add value to it, that's a good thing."

James Nolan, left, 41, a local 608 carpenter and first responder on 9/11, suffers from upper and lower pulmonary infection, an enlarged liver, rash on his hands, high blood pressure, and a compromised immune system. He spent two and a half years working at Ground Zero. Photo by Enid Alvarez/New York Daily News. Vito J. Valenti, far right, is on many medications and has to breathe oxygen due to lung problems he developed after working on the 9/11 site. His father, Joseph, left, has moved in to help care for him. 2006. Photo by Frank Koester.

Public Service Journalism

The series did just that, drawing on interviews with doctors who ran 9/11 clinics, experts in pulmonary disease, federal, state and city officials, members of the health, police and fire departments and their unions. The Daily News also interviewed Workers' Compensation Board members and lawyers, members of Congress, including Senator Hillary Clinton and Representative Carolyn Maloney, mayoral and gubernatorial aides, responders' survivors and their attorneys, and dozens of firefighters, police officers, construction workers, and cleanup volunteers. The team also combed through Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) documents, questionable statements to the public from then-EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman and then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani, and transcripts of congressional debates that found surprising precedents in issues of workers' compensation for civilians that arose after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Beginning July 23, 2006, almost five years after the WTC fell, the Daily News published the opening editorial in a campaign titled "9/11: The Forgotten Victims — A Call to Action." The paper's editorial board produced 13 prominent editorials in 2007, including some featured on the front page, and the Daily News supplemented the series with editorial cartoons and letters to the editor.

By marshaling the facts in a way no one had done before, the Daily News editorial page built an unimpeachable case that the illnesses were real and presented harsh indictments of public officials who denied care to rescue and recovery workers. Most importantly, the Daily News demanded — and got — action. After years of studied ignorance, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released $75 million — the first federal aid — dedicated to treating 9/11 responders. The state eased workers' compensation rules; the city began funding treatment programs. And the newspaper, through its editorials, provided much-needed facts to stricken responders.

In retrospect, it is startling to consider how little was known about the epidemic of lung diseases afflicting 9/11 workers before the series ran. In the 58 months after 9/11, New York City's five general-interest newspapers — including The New York Times — never once printed the term "reactive airways distress syndrome," although the asthma-like condition was growing into a prevalent debilitating ailment among responders. Now the diseases suffered by the rescue and recovery workers — and their sometimes fatal consequences — are accepted fact.

Given the hard times newspapers find themselves in, now more than ever investigative reporting and public interest journalism should be encouraged and applauded no matter where it appears — including on the editorial pages. By marrying reportorial resources with an editorial board's ability to take sides on important issues and prescribe remedies, the Daily News produced a groundbreaking series that got help for thousands of people. We hope other newspapers will find inspiration in this example.

Heidi Evans, a 1993 Nieman Fellow, is a staff writer for the Daily News. Beverly Weintraub is a member of that newspaper's editorial board. To read the editorials, go to www.pulitzer.org, and click on 2007 winners, editorial writing.