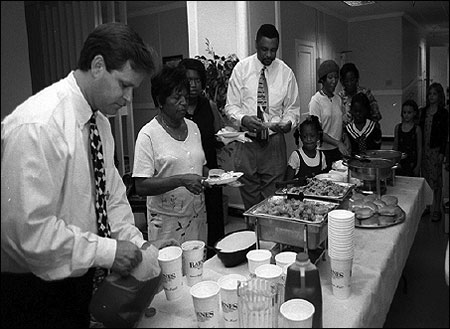

Reception for Neighborhood Newsroom graduates attended by the graduates and staff members. Photo by Bob Morris, Savannah Morning News.

Steve Corrigan, editor of the Closeups section of the Savannah Morning News, stood beside me, giving slight nods as he made some introductions while showing me the busy newsroom.

“What do you see?” he asked. His question caught me off guard. He paused, but in a moment continued speaking. “All white faces,” he said, “and that’s what we hope to change with the Neighborhood Newsroom Program.”

A quick survey of the newsroom confirmed what his eyes and mine saw. There were no faces that looked like mine. To be sure, racial diversity has made inroads in many public arenas but it still has a way to go in many parts of the private sector, including this part. The absence of faces like mine—and the voices and experiences connected to those faces—is one reason why minorities feel disconnected from this newspaper and other media. It’s also why feelings of one-sidedness arise at times when stories about murder or robbery of someone of another race appear in the news. And it’s why magazines such as Ebony and Jet remain so popular.

When a face like mine is part of an enterprise, it sends out a signal that chances for fair treatment have increased. Perhaps when a minority event is mentioned in the newspaper that story will carry the same significance as others. Maybe when newsroom staffs are composed of many different faces, expressions used in conversations such as “he was giving me funny looks”—which in some instances has led to murder—would be better explained to readers.

I thought about this as I watched a courtroom scene on television. It was a case involving two young boys and a woman who have different racial identities. The boys wanted to play in the area and asked the woman when she intended to move her vehicle. The woman didn’t answer the boys, and when she wasn’t looking, she thought the boys damaged her car. The judge asked her why she didn’t answer the boys. “I don’t play with children,” she replied. The judge ruled in her favor but commented that the boys deserved an answer. It seemed that the judge misunderstood what the woman meant by her response. To my ear, she was saying that the boys were so rude and disrespectful in the way they asked this woman that she regarded them as little miscreants. To answer them would be to involve herself in a war of words that could easily escalate into something a lot more serious.

To hear Steve say the paper wanted to diversify the newsroom caused my eyebrows to arch and my mouth to draw down in an inaudible “Huh!” He had my attention more so now than the day I was introduced to him by Polly Stramm Powers, a freelance writer. She’d read a story I’d written about an early morning exercise class we both attended. I wrote the story after reading an article written by a visiting journalist who was on assignment to write about the effects of exercise on women over the age of 50. Our instructor wasn’t pleased with that story and let us read it. I thought, “I could do better than that.” Polly thought the newspaper would be interested in my work and arranged a meeting for Steve and me.

That day Steve told me what I’d written was good. He encouraged me to continue writing as a way to improve. He explained he was looking for human-interest stories and people who would be more than a one-time wonder to write them. The pay for each story would be enough for an evening at one of Savannah’s finer restaurants. Steve’s encouraging words stuck in my mind. Such words can be the catalyst that causes an ego to take flight and reach for perfection. Mine had certainly left the runway.

I left that meeting with a better idea of what the paper wanted. I wrote an article about a young woman whose fingernails were three inches long but still operated a cash register and put away stock. That story, along with photographs I’d taken, made the front page of the Closeups section in its entirety, almost as I’d written it.

For 19 1/2 years, I’d worked as a pipefitter, a job I’d been trained to do and had hoped to do for many, many years. But an injury made this impossible, so I was delighted to be able to think that I might be able to become a journalist. The Morning News Neighborhood Newsroom Program—a four-week training session created to prepare novices as well as experienced writers for what work in a newsroom requires—was the paper’s vehicle to crack open the door to diversity, and it offered me a chance to step through. The program drew a cross section of mostly minority women including a college professor, a professional writer, college students, a sales clerk, teachers and me, a pipefitter in search of a new career.

Each night we met the chairs were arranged in a different configuration, a touch that added to the excitement and helped to get my creative juices flowing. Notebooks were supplied. Various groups were formed at different times and assignments were given.

One evening our nine chairs were arranged in a horseshoe formation. Ewan Watt, a Scottish journalist who was the featured speaker for the evening, stood before us and served up tempting morsels of information about the ways of journalism. Speaking in his entrenched accent, he told about his work at a newspaper in Glasgow. All ears tuned in as he spoke of “details, details” that make a story come alive. At another session Doug Miller, assistant editor on the civic team, took the group on a walking trip around one of Savannah’s beautiful downtown squares. Along the way, he demonstrated how story ideas can emerge from a simple walk, when one constantly asks questions and takes notice of the surroundings. Steve took us to cover a town hall meeting which helped us to use the lessons we’d learned in a previous class about how to sort through information gathered and decide what is the story to be written. What I discovered that day was that the story I thought I’d come to cover might take a back seat to stories I could find being told in the corners of the room, in the back row of the meeting room, or in the parking lot.

Through the four weeks of classes, informative instructors, and sometimes a seasoned reporter, came well prepared to teach us. Topics covered included libel laws and other legal issues, writing ledes and endings, and interviewing skills. David Donald, precision editor, spoke on prewriting techniques. He said the best journalism today answers lots of questions for readers. But the challenge is how a reporter asks the kind of questions that elicit these answers. He also said the writing doesn’t start when you come back to the newsroom. It starts when you arrive on an assignment and begin taking notes. This is something I still struggle with.

One topic that held my attention was a presentation about “thinking outside the box.” Thoughts other than the norm have always been with me, but in some circles my way of expressing things was thought of as a bit odd. As a consequence, often I repressed my thoughts. Learning this kind of thinking could be a useful tool in journalism seemed like a bonus for me.

I am not one to blame race for all the ills of the African-American community. There is good and bad on all sides. But try as I might to avoid it, situations frequently develop because of racial differences and can be brought about through their verbal or written exchanges or through action. Through my work in journalism, I hope I can help to rid people of the need to put another person down because of race. As an African American, I’m keenly aware of the lack of stories that speak to me and to my experiences. As I read the paper, I flip past many articles after reading the headlines or seeing photos in which I am not represented. With the newsroom adding faces like mine, maybe the next recruit won’t be caught off guard when the same question is asked of her, “What do you see?” and the answer pertains to race. And possibly readers will not instinctively feel that someone who wrote a story doesn’t understand the colloquialisms or customs of the African-American community.

In the months since the Neighborhood Newsroom Program ended, several stories that my classmates and I have reported and written have been published in the newspaper. My stories aren’t just about African Americans, but I do make a concerted effort to write stories that interest them. I am currently working as a freelance reporter. Most of my stories have appeared in Closeups, a section of the paper inserted into the Wednesday edition. When an opening comes up, I hope to become a staff writer or a columnist. One of the stories I wrote was a story Steve pitched to me about the Savannah Rotary Club’s meeting and accomplishments. The club’s president sent me a note to say thank you. It made me feel I’d done a service for the common good and the public appreciated it.

My goal is to write a story worthy of the front page. I want that story to be fair, honest and without bias. Then I’ll feel I have arrived. The only thing standing in my way is me.

Neighborhood Newsroom graduate Iris Formey Dawson evaluates the program. Photo by Bob Morris, Savannah Morning News.

Margaret Bailey worked for nearly 20 years as a pipefitter. She now writes stories for the Savannah Morning News as a freelancer and hopes to have a full-time staff position soon.