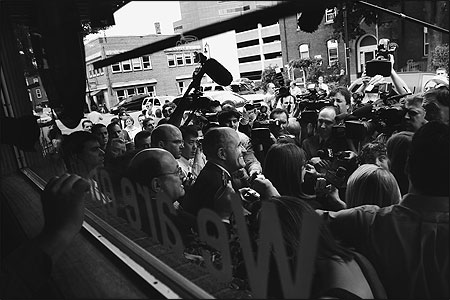

In the annals of adversarial journalism, the dustup between Associated Press political reporter Glen Johnson and presidential candidate Mitt Romney preceding the 2008 South Carolina Republican primary might rate a mention in the next Teddy White-style campaign saga. Sprawled on the floor of a Staples store in Columbia, South Carolina, in the midst of an impromptu press conference, Johnson brusquely interrupted Romney as the candidate professed that no lobbyists were running his campaign. "That's not true, governor. That's not true," Johnson said, as he named a Romney strategist who is a well-known lobbyist.

This brief, heated exchange is familiar to any veteran political reporter who has spent time inside the sometimes fractious "bubble" of presidential campaigns. Familiar, too, is the follow-up confrontation as Romney circled around after the press conference to challenge Johnson with an age-old candidate's lament: "Listen to my words, all right? Listen to my words."

What is different now is the bubble has become a fishbowl. Footage from cable network news cameras captured the entire episode, which included a scolding of Johnson by a Romney aide that he should "act more professionally." Soon, the scene was uploaded onto YouTube and an incident that would have been relegated to a campaign footnote took on a life of its own. In the new camera-rich environment, the video could have just as easily come from a voter's cell phone or the hand-held device of the ever-present campaign trackers.

RELATED WEB LINK

Watch the complete video »

To get a sample of videos on the episode, search “Romney” and “reporter” on YouTube.After some brief exposure on cable news talk shows, the video went viral, and Johnson became a minor YouTube celebrity and a member of the million plus hits club on the Google search engine. The political blogs feasted on the confrontation to the point that The Associated Press (AP) moved a brief story on the Internet uproar. Even in mid-March, two months later, the Johnson-Romney imbroglio could be found on a couple of dozen postings on YouTube.com, with these still registering about 95,000 views.

The plus side of this new media environment is more transparency in newsgathering; the downside is akin to watching sausage being made. In this case, the consequence was that a member of the press corps became the story, rather than how Romney's campaign was connected to lobbyists. Whether Johnson violated a professional norm is not the issue here, although he apparently forgot the legendary AP reporter Walter Mears's instruction to wire service reporters of "keeping yourself out of it."

The Flood of Video

The larger point is that the deluge of online videos flooding the Internet in the 2008 election cycle marks another chapter in the continuing technological transformation of the way Americans receive their political news and how journalists cover campaigns. The campaign has become an even more visual event as pictures crowd out words. Changes we are now experiencing threaten to rival those brought by television news, starting in the 1960's. Then, some journalists feared for the written word and the future of serious political journalism. Those fears seemed exaggerated back then, as television went on to enhance the power of political journalists in the heyday of the broadcast networks.

But the debate over television echoes today. As journalism historian Donald A. Ritchie has written, one of those early television critics was then CBS News correspondent Roger Mudd, who in a 1970 speech issued a warning that seems prescient today. He criticized television for its tendency "to strike at emotions rather than intellect … on happenings rather than issues; on shock rather than explanation; on personalization rather than ideas."

The "YouTubification" of politics is rekindling these fears and this time, possibly with more reason, especially for journalists who get paid to write or air words. A major thrust of the Internet has been to increase the unmediated information flowing to political elites and also to an increasing percentage of Americans. Many applaud the democratization they see happening with the rise of "citizen journalists" who make their own "mash-up" videos. But even a cursory trip through YouTube's political channel finds a lot of videos and ads produced by candidates and snippets of repurposed television news. It is often difficult to ascertain the sources and to figure out just what has been mashed up.

With the facile attraction of highly entertaining videos, the impulse has increased to use the Internet to bypass conventional journalistic coverage. This stampede to video on the Web makes the fear about television's vapidity seem overheated in comparison to the true trivialization made possible by YouTube. Certainly where we've arrived is not the original vision of cyber utopians who foresaw in the Web a new agora — an arena of political discourse and not one saturated by television spots and sound bites.

Take, for example, a mash-up video promoting Senator Barack Obama, "Yes We Can," produced by a pop singer named will.i.am. It might not have contributed much to the political dialogue but, as of late March, it had drawn 17 million views on YouTube. By comparison, Obama's March 18th speech on racial reconciliation drew less than a fifth that many views on YouTube, although it was still a substantial audience. Then, of course, there are this election season's iconic videos — the "Obama Girl," the "Sopranos" video featuring Bill and Hillary Clinton, John Edwards' obsessive hair combing, and Chuck Norris's macho, fist-in-camera endorsement of Mike Huckabee. All of these drew big numbers on YouTube and also extensive coverage by a news media that have never overcome the allure of the Internet as a source of the bizarre.

According to a poll by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press released in January, a quarter of Americans in the 2008 election regularly turn to the Internet for information about the presidential race. That is almost triple the percentage found by the center in a poll in 2000 when this new medium was blossoming. More interesting for the future, the Pew poll found that 42 percent of 18 to 29 year olds are using the Internet for campaign information, with much of that flowing through social networking sites like MySpace and Facebook. And the poll found that four-in-10 of the younger cohort have watched at least one form of campaign video online, double the frequency among those 30 or older.

With younger audiences' news habits now better understood, it seems clear where we're headed.

The Road We've Traveled

RELATED WEB LINK

Download the study, funded by Pew Charitable Trusts. (pdf) »

RELATED ARTICLE

"The Jigs and Jags of Digital Political Coverage"

— Albert MayThe 2000 election witnessed the first significant use of online videos. But they were a flop, as was described in a study I led in 2002 entitled "The Virtual Trail: Political Journalism on the Internet." Back then, the technology simply wasn't ready. Journalists who we interviewed ranked online videos as very low in usefulness. A bold experiment by The New York Times and ABC News was a 15-minute Webcast called "Political Points" that aired daily through the 2000 election. Impossible to watch on dial-up and pretty jerky on broadband, we deemed this effort the "greatest journalistic effort for the fewest viewers." The show died after the election, and similar sustained efforts at original political programs as Webcasts have not been repeated. Even today, Webcasts as original programming have evolved into three-to-five minute bursts of commentary or talking-head reporting that often have production values reminiscent of 1950's television.

In the campaign summer of 2004, video re-emerged in a different, edgier format and made a huge media splash. JibJab.com's "This Land" video, first spread virally by e-mail, broke into the mainstream media in mid-July. Set to the tune of the Woody Guthrie song, the cartoon parody featured the Bush character calling the John Kerry character a "liberal weiner," who in turn responded with "right-wing nut job." Estimated audience: 50 million, as television news replayed it around the world.

RELATED WEB LINK

Download "Under the Radar and Over the Top" (pdf) »As a study by the Institute for Politics, Democracy & the Internet found, however, JibJab was just one (a mild one at that) of the hundreds of inflammatory videos that circulated by e-mail that year. This study, "Under the Radar and Over the Top," captured both the lack of press scrutiny and the often outrageous content of the videos. The institute collected about 150 examples; some were funny, but many were hyperpartisan and obscene. The videos gained a large audience among political elites, as they forwarded them to colleagues. But without a centrally organizing Web site with easy posting of video by anyone with a digital camcorder, laptop and inexpensive software, viewing didn't happen among those who lacked a connection to the political underground.

All of this changed with the February 15, 2005 launch of YouTube.

In our 2002 "Virtual Trail" study, we found journalists generally unsure of how serious to take what was happening online with the campaigns. I remember asking Matt Cooper, then with Time, when we would know that the Internet was a factor, and he said, "When somebody gets beat by it." That happened to Republican Senator George Allen of Virginia in the famous 2006 "macaca" episode, when he aimed the slur at a "tracker" of his Democratic opponent who was of Indian descent. The video spread on YouTube, where it registered half a million views, then ignited in the blogosphere before it bubbled up in the mainstream media.

By the start of this election cycle, numerous one-man-band reporters embedded in campaigns by TV networks and aggressive outreach by some news organizations to get citizens to send in videos (often shot from cell phones) created the fishbowl in which the AP's Johnson found himself.

There are positive aspects for journalists and the civic-minded. Young people's attraction to video is undeniable, especially its shared use in their online social networks. When CNN partnered with YouTube in July 2007 for the first of two presidential debates, some reviewers bemoaned the use of a melting snowman to ask a question on global warming. But CNN reported that the debate drew the largest audience of 18-to-34 year olds in cable news programming history. And the ease of access — and with it a sense of empowerment — facilitated by the Internet is surely a factor in the surge in interest in the 2008 campaign.

REFERRED ARTICLES

"Determining If a Politician Is Telling the Truth"

— Bill Adair

"For Campaign Coverage, Web Too Often an Afterthought"

— Russ WalkerStarting in 2004 and accelerating in 2008, the Internet and the easy availability of videos from the campaign trail also has revitalized and enriched the "truth testing" of candidate advertisements and other messages. This movement began in the early 1990's, but faded, until Factcheck.org, a project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, revolutionized the use of a Web site for in-depth fact-checking four years ago.

Now news organizations, from newspapers to local television, use the Web to extend the reach of their traditional coverage of candidate truthfulness. Yet, in 2008, in the spirit of our times, truth testing is taking a saucier approach than the sober appraisals of the past. The St. Petersburg Times and its sister organization, Congressional Quarterly, launched PolitiFact.com, which uses catchy "Truth-O-Meters." Washingtonpost.com started its site Fact-Checker that awards "Pinocchios'' in measuring candidate veracity. The New York Times and National Journal have also built Web sites deep in videos and content. And where do they get many of their videos? YouTube, of course.

Albert L. May, a 1987 Nieman Fellow, is associate professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University.