If you have taken a picture and shared it with no text, or studied a news image to see if it was “real,” or wondered if “photography” is an accurate term for the digital wave overwhelming and manipulating our social and political lives, then you understand that we are in a visual revolution that is fundamentally altering our everyday experience.

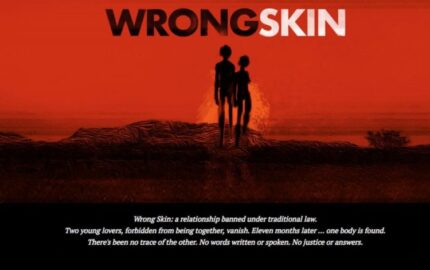

The digitally constructed image, which many argue is no longer a “photograph” at all, clearly has the capacity for destructive possibilities. But we’re just scratching the surface of the positive potential of the medium for inclusion, contextualizing, and vibrant expression. This visual revolution is radically inviting new perspectives, tapping a broader audience reach, and using a solutions-oriented framing of narratives to engage audiences distrustful of the news.

Welcome to the renaissance of visual storytelling that is morphing and shaping our understanding of the world, and ourselves.

Truth has always been malleable and subjective, only more so today where visual media lends itself entirely to manipulation and falsification. In looking at an image today we are left wondering: What is it? Can it be trusted? What exactly is it telling us? We are analogously asking the same questions of our government and media institutions, which seem to be devolving symbiotically from what we’ve come to know and rely on. Truth is being questioned on every front.

What are we left with? We crave what is real, and we long for context and perspective. The current visual revolution is delivering on both.

We crave what is real, and long for context and perspective. The current visual revolution is delivering on both

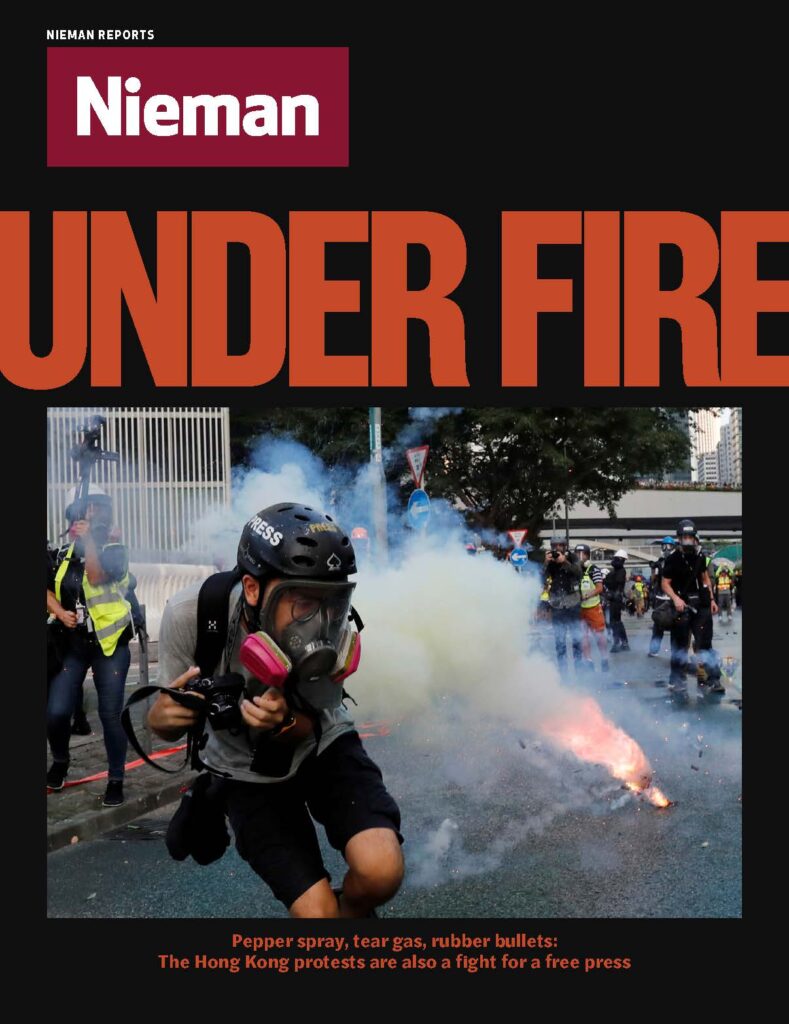

Photojournalism is vibrant today in the expanded medium of visual journalism, including all camera-based medias—stills, video, virtual and augmented reality—and in complementary multimedia, including audio, geolocating, illustrations, and text. This explosion of innovation is rewriting the way we define journalistic practice. As new tools for capture and distribution are becoming mainstream, and against the backdrop of a highly charged political climate, there has never been a better time to pay attention to the energy and ideas in visual journalism.

Here are some compelling examples of innovators responding creatively and constructively to the urgency of the moment, and rethinking the delivery of the news:

COUNTERNARRATIVES

Alexandra Bell is an artist exploring how images influence the way we shape opinions. She exposes gender and racial bias in high-profile newspapers by challenging the perspectives that shape the narratives and image choices in prominent headlines. “Whose story is being told here?” she asks, through “Counternarratives,” her flagship project re-imagining the front page. She is not questioning the facts of the story, but wants to present a different narrative vantage point as a way to explore another side of “the truth”.

She has challenged the visual presentation of hotly contested issues like a hate crime in Tulsa (new headline: “White-American Man Charged With Murder”) or racial violence in Ferguson (new headline: “A Teenager with Promise”), displaying her redesigned front page news in large-scale public art. According to Bell, “This isn’t a grammar exercise; I’m really trying to see if I can disrupt subliminal messaging about who should be valued.” The work has spread beyond New York City to other U.S. cities, magazines and museums. Her next project is a futuristic newspaper in which critical issues plaguing marginalized communities — income inequality, criminal justice, and housing access — are being reported in a solutions mode, as people work to solve shared problems.

DYSTURB

Dysturb uses “the most basic of social networks, the streets,” to rediscover audiences who don’t trust the news. “Dysturb is at the crossroads of journalism, street art and community engagement, which is a great way to reach youth,” says co-founder Pierre Terdjman, working with fellow French photojournalist Benjamin Pettit. Also using street walls as a platform for commercial-scale, public art, they feature “guerrilla blowups” of social issues relevant to that neighborhood — “activations” meant to literally “disturb” pedestrians with images that are provocative enough to get the attention of cynics who don’t see the news as impacting their lives.

The issues — climate change, homelessness, women’s health — challenge the online world of filter bubbles by physically meeting people where they are. Context and deeper engagement come via text and QR codes, which link to the voices of the photographers or subjects. The Dysturb team also visits classrooms, prisons and hospitals to teach general media literacy and to promote awareness for freedom of the press in democratic societies.

Dysturb’s programming leads with the image to give voice back to photojournalists as frontline witnesses to the story. Working with partners, including the United Nations and Instagram, they have been in 130 cities globally. In 2018, the #reframeclimate campaign featured 37 global photojournalists in San Francisco supporting The Global Climate Action Summit. The #Womenmatter campaign addresses violence against women in five cities globally. The intent is to push back on a fast-paced news cycles by stopping people in their tracks with powerful visuals and relevance. Says Terdjman, “Photojournalism is a universal language with the power to demolish stereotypes. It can trigger discussions, alert consciences and assist people with the keys to better understand world events.”

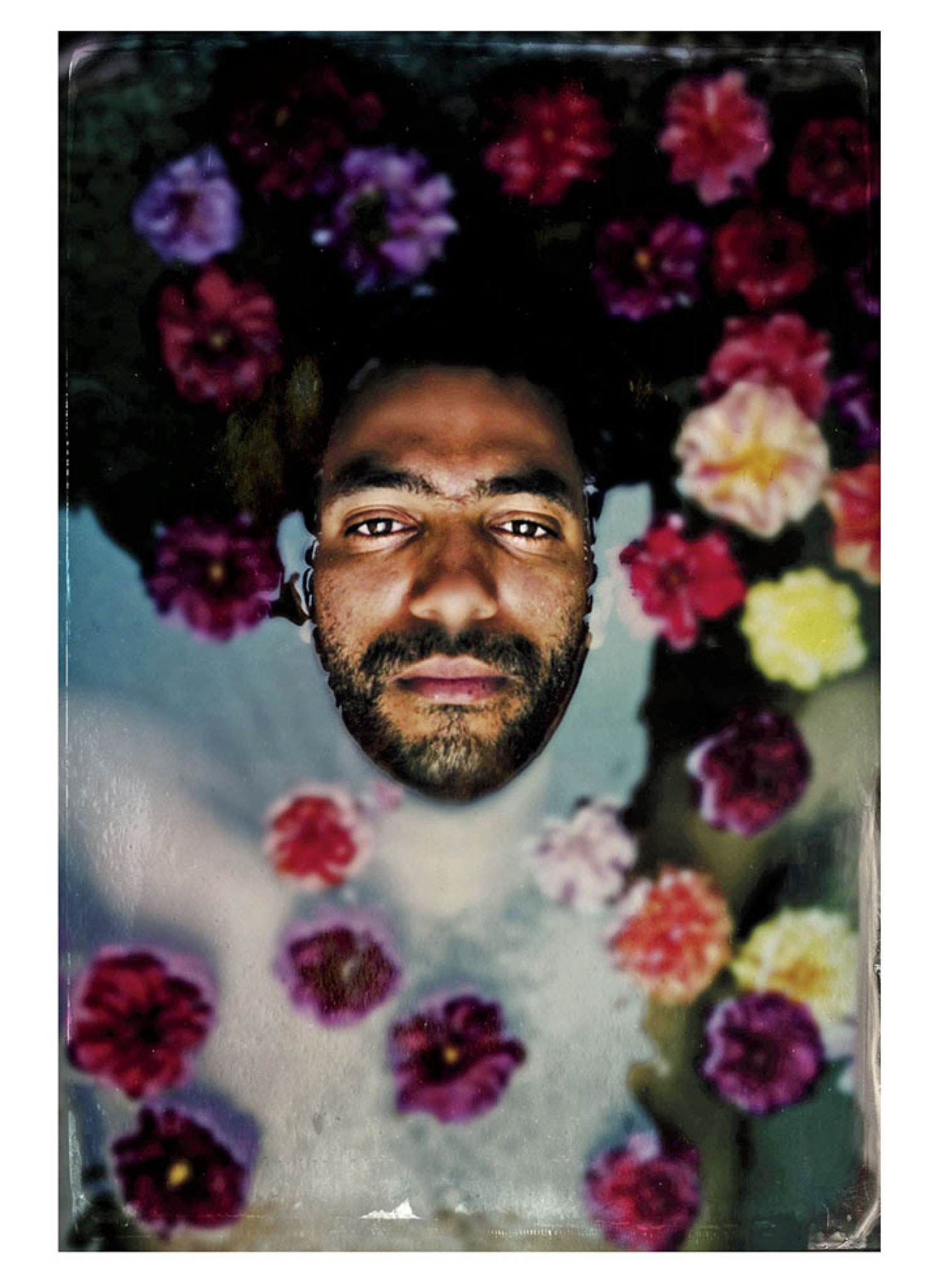

HER TAKE

Seven women from New York-based VII Photo Agency are exploring the historical “male gaze” of photojournalism and art in a diverse world with “Her Take: (re)Thinking Masculinity.” Examples: How to cover the male body as explicitly and intently as the female body in Western art; an examination of gender and non-binary framing; or the tropes of African manhood. The underlying question is: Why does it matters who tells our stories? Why, indeed?

Artists and social entrepreneurs are taking a fresh look at diversification behind the lens with online platforms making it easier to find a skilled bench of women and people of color in photography. Women Photograph presents a curated group of 800 women (trans, queer and non-binary people) from 99 countries available for photo commissions; a granting arm builds growth in the field; and they hold the global press accountable by publishing statistics on gender inclusion in lead photo bylines: The 2018 average was 17%.

Rawi’ya Collective is a group of pioneering women photojournalists from the Middle East working to shift the portrayal of Arab women in Western media with deeper and more intimate storytelling. And the Authority Collective is a membership of female, transgender and nonbinary photographers organized to promote networking, peer support and collaborative story development ideas. “We certainly need more diversity in the photo corps, but we also need the people in positions of power to have drastically different approaches in how to tell stories,” says Tara Pixley, a founding member. “As photojournalists, our job is to tell the world about itself; this is our moment to shine and to be the best tool for democracy that we can be.”As the industry shrinks and shifts, no clear data on the true population of photojournalists by gender and demographics is available. World Press Photo reveals women were fewer than 20 percent of more than 5,000 photojournalists who applied for Photo of The Year in 2019.

Embedded in the current Wild West of visual storytelling are many dangers

Women are moving into higher visibility in media organization management, according to a new study by the International Women’s Media Foundation. But in photojournalism, the negative impacts of shrinking job opportunities and rising violence in international reporting have simply made it more difficult for women to work in the field. Photographer Yunghi Kim, in a recent Medium article, “Gaslighting in Photojournalism,” worries that an entire generation of remarkable female photojournalists from the 20th century are overlooked in this rush to champion the current breaking of a glass ceiling.

And there needs to be a conversation about who is paying for today’s visual journalism. Current industry trends and the ubiquity of the medium blur the lines between photojournalism and advocacy image-makers, between professional journalists and amateurs with on-the-spot captures. With shrinking or vanishing photo staffs, today’s news organizations sometimes turn to these crowd-sourced images. Philanthropy is stepping in to support some of the emerging visual journalists. But while that promotes the ecosystem at large, it also seeds confusion about authenticity and journalistic objectivity. (Disclosure: I founded an organization, Catchlight.io, to help discover and develop visual storytellers who can help make sense of a complicated world.)

The 1960s media theorist Marshall McLuhan believed that the way people consumed information mattered more than the information itself. Famously coining the observation that “the medium is the message,” he was concerned about the impact of the televised image on American civic life. Photojournalism then was evolving from newspaper stills to televised video. Now, it has transformed itself into visual journalism, providing the vast array of media that glue us to the small screens that we carry in our pockets.

Embedded in the current Wild West of visual storytelling are many dangers — image manipulation, a growing unease with the institutions our democracy relies on, and a general distraction from our civic duties, as noted by Neil Postman in “Amusing Ourselves to Death.” However, these new models demand our attention as they break rules and reinvent the delivery of stories that form the connective tissue of our communities.

A visual revolution is underway, and many of the innovators are dynamic and principled, working to help us understand the world around us accurately, intelligently and respectfully. They are driving excellence in imagery in our news today. Our democracy rests on just this kind of courage and social optimism.