RELATED ARTICLE

"Noticing Quiet Amid the Battles of War"

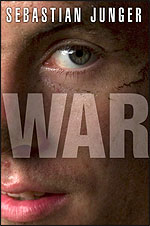

- Chris Vognar When journalists go into war zones, some of them are there to report the news of battles fought, of ground gained or lost, and of soldiers hurt or killed. Others remain with soldiers for a longer time, embedded in their unit, and over time they become embedded in their lives. It becomes their purpose to absorb what it means—and convey what it feels like—to be a soldier fighting this war. Such is the vantage point of author and journalist Sebastian Junger who emerged from his time in Afghanistan with a book called “War” and a companion documentary film, “Restrepo,” co-produced with photojournalist Tim Hetherington. In these essays, we offer the perspective of a soldier who served in Iraq and Afghanistan on how well Junger succeeded with “War” and of a movie critic, Chris Vognar, who writes about “Restrepo.”

Such is the raw power of Sebastian Junger’s book “War,” which follows a platoon stationed in the harsh Korengal Valley of Afghanistan, that I found myself responding with a visceral memory of my own combat service in Iraq and Afghanistan. As I followed Junger’s portrait of the Second Platoon, Battle Company of the storied 173rd Airborne Brigade, I completely understood the intense bonds of friendship the young soldiers formed with one another, immersed as they were in an alien landscape, wholly reliant upon each other, and under constant threat of mortal danger.

I joined the Army in the aftermath of 9/11, having graduated from Harvard College that June. I had been the happy beneficiary of almost every advantage a free and prosperous society offered. It seemed only fair, right and just that I spend time giving something back to the great country that had given me so much. But what began as a selfless pursuit quickly became a selfish one, for joining the military proved to be the start of a journey during which powerful friendships, much as those Junger describes, were forged in the fires of hardship, isolation and danger.

Junger tells what may seem to many a chilling story. When the men at the firebase heard on the radio that an injured Taliban fighter had died of his wounds after crawling “around on the mountainside without a leg,” they cheered. I remember all too well experiencing similar emotions while leading my platoon in Baghdad. On our nightly patrols we were either looking for insurgents to shoot or just waiting for them to shoot at us so we could return fire and kill them.

On nights when we took fire but were unable to positively identify the targets in order to kill them in turn, I experienced an intense frustration, even rage. Given the hit and run tactics, the improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and the indirect fire of the conflict at that time, this was a fairly common occurrence. Hours later, however, back in the safety of my bunk, I couldn’t conceive that I had mustered such strong emotions simply because I had been denied the opportunity to take a life. The very thought that I hungered for it seemed disgusting to me. Even still, the feeling returned time and time again.

Conversely, when we were able to find our attacker, the feeling was not one of satisfaction that one would assume to be the natural counterpoint of the earlier frustration. There was no celebrating, there was no sense of triumph, instead there was an intense sadness, especially when the collection of the body almost inevitably revealed a man whose youthful features were so evocative of the men of my platoon.

Junger clearly articulates one of the primary ways in which men justify these killings. “You’re thinking that this guy could have murdered your friend,” one of the soldiers tells Junger. “People think we were cheering because we just shot someone but we were cheering because we just stopped someone from killing us.” Junger himself recognizes this very personal aspect of armed conflict when he ruminates on the individual whose IED just barely failed to kill him. He is shocked by “the raw fact that this man wanted to negate everything I’d ever done in my life or might ever do.”

For me, such rationales, necessary to maintain a bit of sanity in the insanity of combat, break down when innocent civilians are killed. While in Afghanistan from 2008 to 2009, one of my responsibilities was to help investigate allegations of major civilian casualty incidents potentially caused by NATO and international forces. In one instance we went to a camp of nomads where a U.S. missile had struck the night before, seeking out, in vain, a “high value target.”

We landed one hilltop over from where the Kuchi nomads had established their camp. For the most part, the actual body parts had been cleared out—however, the destruction visited by the U.S. ordnance was such that there were still remnants strewn throughout the area, most barely recognizable and indistinguishable from the livestock that had been in the kill zone. Indeed, the most recognizable human remain was the oddly preserved decapitated head of a 12- to 14-year-old boy. No matter how carefully constructed your emotional and intellectual justifications for the horrors organic to armed conflict, it is difficult to emerge whole from such experiences.

In fact, many do not emerge unscathed. Junger’s primary protagonist, Sergeant Brendan O’Byrne, is one of those. Serving as the voice of the platoon, his character is more fully realized than any, save Junger himself. As such, it is particularly painful to watch his slow demise when he returns from the deployment, first to his home base in Italy and ultimately out of the Army in the United States. He drinks heavily, begins to see enemies where none exist, and ultimately needs an officer’s assistance to be allowed to return home rather than go to jail. As he writes to Junger, “A lot of people tell me I could be anything I want to be. If that’s true, why can’t I be a fucking civilian and lead a normal fucking life?”

After our arduous deployment, this was a question tacitly asked by members of my company and platoon as they experienced a similar downward spiral. Some lost years to drinking, one went to jail for assault, numerous marriages did not survive. Others, sent back to Iraq and Afghanistan for multiple redeployments, lost their lives.

I believe post-traumatic stress disorder is not simply a function of images that cannot be forgotten, actions that cannot be rationalized. The returning soldier is no longer part of a group bound together by a clear sense of purpose, familiar rituals, and shared experiences. Relationships forged under fire cannot be easily recreated in the modern world or even understood by anyone who has not been in combat. This is especially pronounced in the modern era of warfare, when such a tiny percentage of the population is actively engaged in America’s conflicts. Yet, if we are to reach our troubled soldiers, we must begin to understand that feelings of isolation and the absence of camaraderie combined with the loss of clear purpose weigh as heavily as the memories of the bodies, bombs and bullets.

Joseph Kearns Goodwin, a former captain in the U.S. Army, served as a platoon leader in Iraq between 2003 and 2004 and as a top aide to the director of strategic communications in Afghanistan from 2008 to 2009. He is now in law school.

"Noticing Quiet Amid the Battles of War"

- Chris Vognar When journalists go into war zones, some of them are there to report the news of battles fought, of ground gained or lost, and of soldiers hurt or killed. Others remain with soldiers for a longer time, embedded in their unit, and over time they become embedded in their lives. It becomes their purpose to absorb what it means—and convey what it feels like—to be a soldier fighting this war. Such is the vantage point of author and journalist Sebastian Junger who emerged from his time in Afghanistan with a book called “War” and a companion documentary film, “Restrepo,” co-produced with photojournalist Tim Hetherington. In these essays, we offer the perspective of a soldier who served in Iraq and Afghanistan on how well Junger succeeded with “War” and of a movie critic, Chris Vognar, who writes about “Restrepo.”

Such is the raw power of Sebastian Junger’s book “War,” which follows a platoon stationed in the harsh Korengal Valley of Afghanistan, that I found myself responding with a visceral memory of my own combat service in Iraq and Afghanistan. As I followed Junger’s portrait of the Second Platoon, Battle Company of the storied 173rd Airborne Brigade, I completely understood the intense bonds of friendship the young soldiers formed with one another, immersed as they were in an alien landscape, wholly reliant upon each other, and under constant threat of mortal danger.

I joined the Army in the aftermath of 9/11, having graduated from Harvard College that June. I had been the happy beneficiary of almost every advantage a free and prosperous society offered. It seemed only fair, right and just that I spend time giving something back to the great country that had given me so much. But what began as a selfless pursuit quickly became a selfish one, for joining the military proved to be the start of a journey during which powerful friendships, much as those Junger describes, were forged in the fires of hardship, isolation and danger.

Junger tells what may seem to many a chilling story. When the men at the firebase heard on the radio that an injured Taliban fighter had died of his wounds after crawling “around on the mountainside without a leg,” they cheered. I remember all too well experiencing similar emotions while leading my platoon in Baghdad. On our nightly patrols we were either looking for insurgents to shoot or just waiting for them to shoot at us so we could return fire and kill them.

On nights when we took fire but were unable to positively identify the targets in order to kill them in turn, I experienced an intense frustration, even rage. Given the hit and run tactics, the improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and the indirect fire of the conflict at that time, this was a fairly common occurrence. Hours later, however, back in the safety of my bunk, I couldn’t conceive that I had mustered such strong emotions simply because I had been denied the opportunity to take a life. The very thought that I hungered for it seemed disgusting to me. Even still, the feeling returned time and time again.

Conversely, when we were able to find our attacker, the feeling was not one of satisfaction that one would assume to be the natural counterpoint of the earlier frustration. There was no celebrating, there was no sense of triumph, instead there was an intense sadness, especially when the collection of the body almost inevitably revealed a man whose youthful features were so evocative of the men of my platoon.

Junger clearly articulates one of the primary ways in which men justify these killings. “You’re thinking that this guy could have murdered your friend,” one of the soldiers tells Junger. “People think we were cheering because we just shot someone but we were cheering because we just stopped someone from killing us.” Junger himself recognizes this very personal aspect of armed conflict when he ruminates on the individual whose IED just barely failed to kill him. He is shocked by “the raw fact that this man wanted to negate everything I’d ever done in my life or might ever do.”

For me, such rationales, necessary to maintain a bit of sanity in the insanity of combat, break down when innocent civilians are killed. While in Afghanistan from 2008 to 2009, one of my responsibilities was to help investigate allegations of major civilian casualty incidents potentially caused by NATO and international forces. In one instance we went to a camp of nomads where a U.S. missile had struck the night before, seeking out, in vain, a “high value target.”

We landed one hilltop over from where the Kuchi nomads had established their camp. For the most part, the actual body parts had been cleared out—however, the destruction visited by the U.S. ordnance was such that there were still remnants strewn throughout the area, most barely recognizable and indistinguishable from the livestock that had been in the kill zone. Indeed, the most recognizable human remain was the oddly preserved decapitated head of a 12- to 14-year-old boy. No matter how carefully constructed your emotional and intellectual justifications for the horrors organic to armed conflict, it is difficult to emerge whole from such experiences.

In fact, many do not emerge unscathed. Junger’s primary protagonist, Sergeant Brendan O’Byrne, is one of those. Serving as the voice of the platoon, his character is more fully realized than any, save Junger himself. As such, it is particularly painful to watch his slow demise when he returns from the deployment, first to his home base in Italy and ultimately out of the Army in the United States. He drinks heavily, begins to see enemies where none exist, and ultimately needs an officer’s assistance to be allowed to return home rather than go to jail. As he writes to Junger, “A lot of people tell me I could be anything I want to be. If that’s true, why can’t I be a fucking civilian and lead a normal fucking life?”

After our arduous deployment, this was a question tacitly asked by members of my company and platoon as they experienced a similar downward spiral. Some lost years to drinking, one went to jail for assault, numerous marriages did not survive. Others, sent back to Iraq and Afghanistan for multiple redeployments, lost their lives.

I believe post-traumatic stress disorder is not simply a function of images that cannot be forgotten, actions that cannot be rationalized. The returning soldier is no longer part of a group bound together by a clear sense of purpose, familiar rituals, and shared experiences. Relationships forged under fire cannot be easily recreated in the modern world or even understood by anyone who has not been in combat. This is especially pronounced in the modern era of warfare, when such a tiny percentage of the population is actively engaged in America’s conflicts. Yet, if we are to reach our troubled soldiers, we must begin to understand that feelings of isolation and the absence of camaraderie combined with the loss of clear purpose weigh as heavily as the memories of the bodies, bombs and bullets.

Joseph Kearns Goodwin, a former captain in the U.S. Army, served as a platoon leader in Iraq between 2003 and 2004 and as a top aide to the director of strategic communications in Afghanistan from 2008 to 2009. He is now in law school.