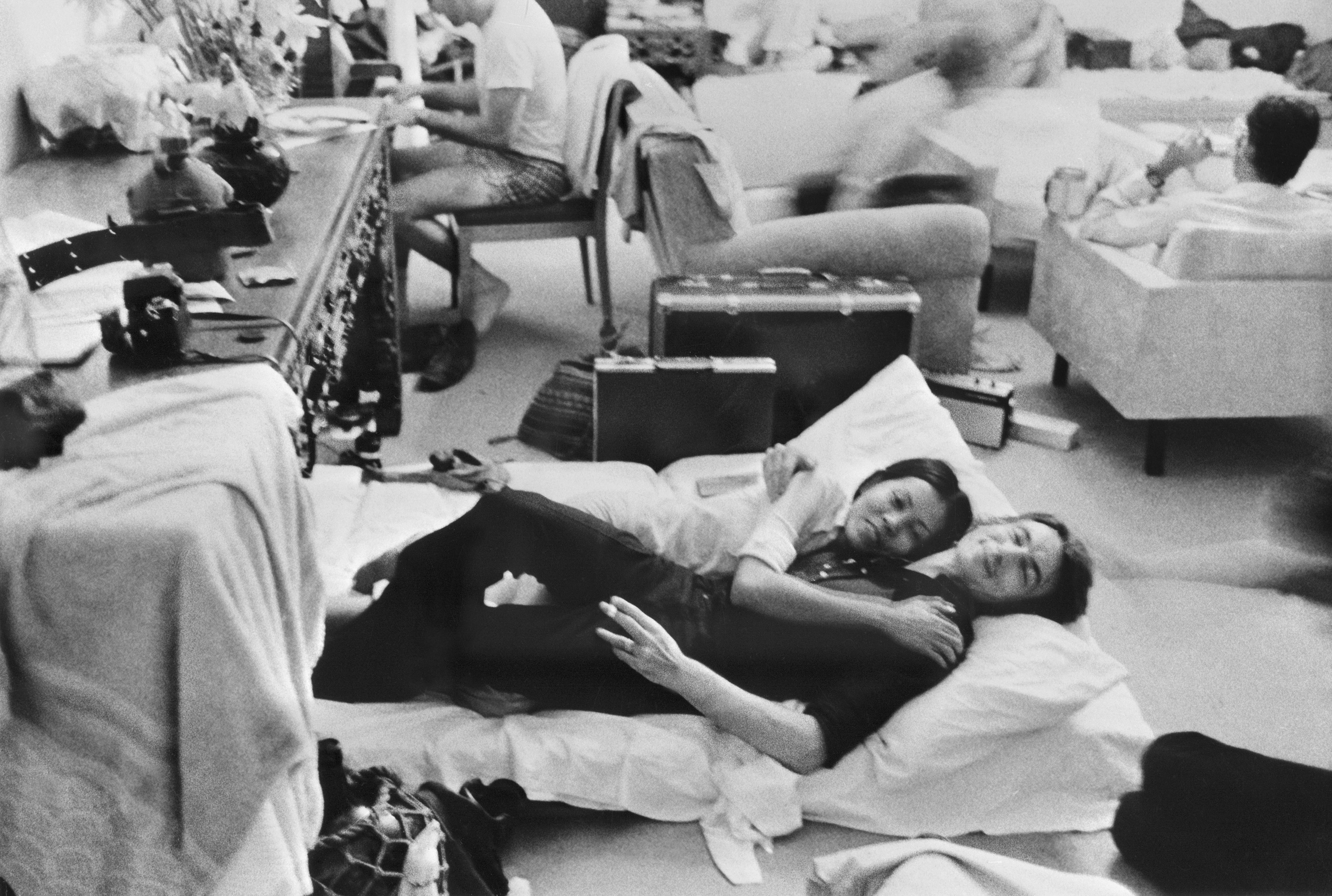

When I first read this front-page dispatch by Sydney H. Schanberg of The New York Times in May 1975, I was covering the labor beat for The Philadelphia Inquirer and still honing the most basic tools of reporting and writing for a newspaper. In this piece (“Grief and Animosity in an Embassy Haven”), written after the Khmer Rouge had taken over Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, Schanberg wrote about the agonizing two weeks that he and 800 other foreigners had spent inside the French Embassy, with depleted food supplies, a lack of running water, and uncertainty about their fates. I was awed by the poignancy and the precision of Schanberg’s reporting. A baby was born during his confinement; another baby died. A dozen marriages were performed, primarily to prevent either bride or groom from being banished to the countryside. Military men who had served the Cambodian government were removed from the compound to be executed. I marveled at Schanberg’s courage to remain in Phnom Penh after the rebels had ordered all foreign journalists out of the country. For this piece and others, Schanberg was the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1976, a well-deserved recognition for his stellar reporting and writing and the courage to stay with his story.

Grief and Animosity in an Embassy Haven

By Sydney H. Schanberg

The New York Times, May 9, 1975

Excerpt

Throughout our stay the Communists continued their campaign of proving their primacy—refusing to let French planes land with food and medical supplies, refusing to allow us to be evacuated in comfort by air instead of by rutted road in the back of military trucks, and, finally, shutting down the embassy radio transmitter, our only contact with the outside world.

At the same time they did not physically harass or abuse us—the only time our baggage was searched was by Thai customs officials when we crossed the border—and they did eventually provide us with food and water. The food was usually live pigs, which we had to butcher.

Though the new rulers were obviously trying to inflict a certain amount of discomfort—they kept emphasizing that they had told us in radio broadcasts to get out of the city before the final assault and that by staying we had deliberately gone against their wishes—but there was another way to look at it. From their point of view we were being fed and housed much better than their foot soldiers were and should not complain.

But complain we did—about the food, about each other, about the fact that embassy officials were dining on chicken and white wine while we were eating plain rice and washing it down with heavily chlorinated water.

Sydney H. Schanberg © 1975 The New York Times.