In October, as Ebola raged out of control and unsettled much of the world, I began making plans for a reporting trip to West Africa. I had covered a minor outbreak of Ebola in Uganda for Smithsonian magazine two years earlier, and I had become fascinated by the science, the public health issues, and the human drama surrounding the virus. I wanted to write about the epidemic, despite the risks. The question was, how?

A decade ago, when I was correspondent at large for Newsweek, the answer would have been easy. I would have made a few calls, found a fixer, gotten on a plane, and hit the ground running. But like many of my peers who are still journalists, I work as a freelancer, obliged to hustle for assignments and deal with logistics I never had to worry about as a coddled staff correspondent.

I sold an editor at Matter on a long profile of a noted Sierra Leonean doctor who died of the disease in July. But I still had to deal with the complicated logistics.

After reaching out to half a dozen companies I struck a deal for evacuation insurance with Global Rescue, though the fine print indicated that, if I contracted Ebola in Sierra Leone, I’d be flown to Europe only if a rescue plane was available.

I came up with a budget for the trip, but wildly exceeded it. My total expenses—including an unexpected three weeks of quarantine at an Airbnb apartment when I got home, at the request of my son’s nursery—came to nearly $10,000. Given the medical risks and the huge costs, it wasn’t surprising that I hadn’t seen a single other reporter in a week of traveling in the country.

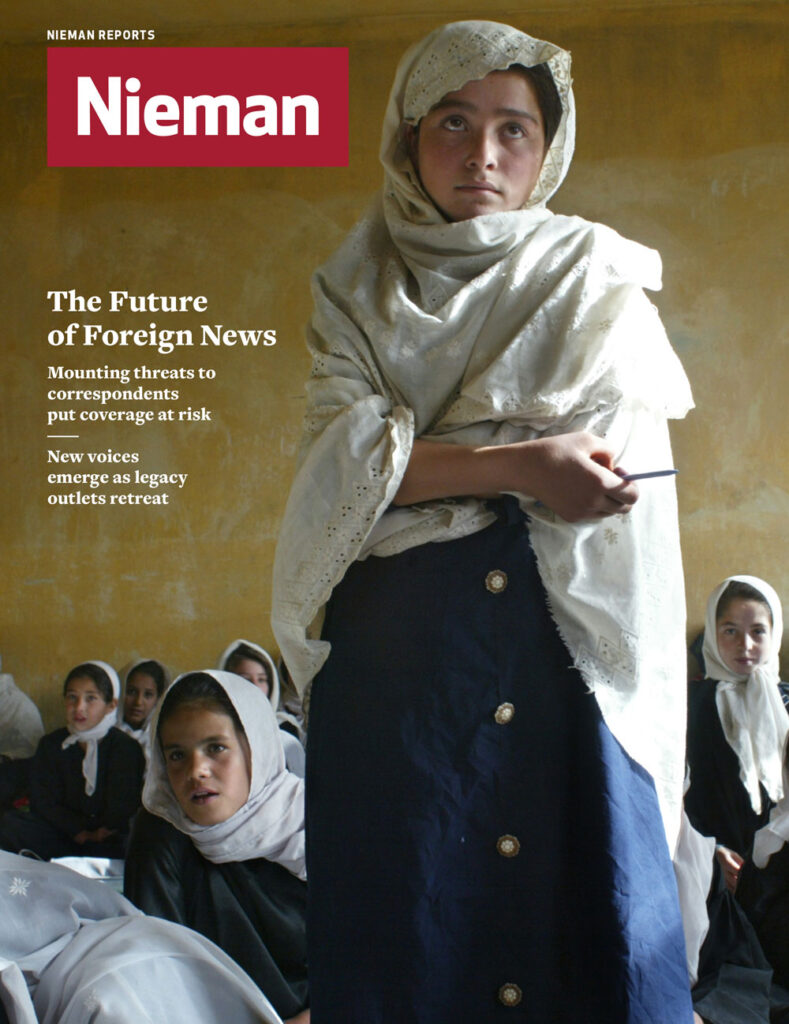

In a year dominated by crises—the twin horrors of Ebola and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Russian President Vladimir Putin’s showdown with the West over Ukraine, the Gaza war—foreign reporting is once again in the spotlight. What’s most striking about the coverage now is just how different the people reporting it look from a decade ago. The veteran correspondents from the so-called legacy media who once flooded the crisis zones have faded away. In their place have come an army of upstarts: staff reporters for new outfits such as Vice Media and BuzzFeed and freelance journalists patching together assignments.

A handful of new digital publications, such as The Atavist and Matter, want long-form narrative, love foreign reporting, and will pay for it. There’s also been an explosion of citizen journalists, including activists and rebels, sometimes armed with nothing more than iPhones and Twitter accounts, who have provided visceral on-the-ground descriptions, if not analysis, of such epochal events as the 2009 pro-democracy protests in Iran and the Syrian civil war.

The abundance of new reporting venues has also given rise to new questions. Are outlets like Vice and BuzzFeed providing the same quality of coverage as The New York Times and The Washington Post? Given the spate of kidnappings in Syria, and the horrific killings of James Foley and Steven Sotloff, are news organizations using freelancers who aren’t adequately prepared? And is it ethical to use their work without giving them the institutional benefits only big outlets can provide?

Another death, in early December, adds urgency to these questions. Freelance photojournalist Luke Somers was killed by his captors in Yemen when they realized a U.S. effort to rescue him was underway.

Since citizen journalists are often the only source of news in conflict zones, how do we know which information to trust? And with nongovernmental organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch becoming more important sources of news, how do we ensure we’re getting information free of any one organization’s agenda? If foreign reporting is replaced by personal opinion and propaganda, what’s left? As NPR’s Deborah Amos says about the civil war in Syria, “The problem is, we really don’t know what’s happening inside.”

In 1993, when I landed my first overseas assignment for Newsweek, as sub-Saharan Africa bureau chief, getting a sense of what was going on inside seemed a lot more straightforward. Newsmagazines and newspapers had the budgets to sustain in-depth reportage by seasoned correspondents. But after I moved on in 1996 Newsweek closed its Nairobi bureau, one of the first casualties in a nearly two-decade retrenchment.

The statistics are sobering. The number of foreign correspondents working for U.S. newspapers dropped from 307 in 2003 to 234 in 2011, according to the American Journalism Review (AJR), a fall of about 25 percent. The number of foreign press members covering the United States mirrors the trend in American reporting abroad. The number of media visas issued by the State Department, an approximation of how many foreign journalists enter the U.S., peaked at 18,187 in the year after the 9/11 terror attacks, but fell to 14,298 in 2013.

The U.S. numbers continue to shrink. Eighteen newspapers, including The Boston Globe and the Chicago Tribune, plus two newspaper chains, closed down all their overseas bureaus between 1998 and 2011, the years that AJR surveyed. The Los Angeles Times has cut its foreign bureaus from 22 in 2004 to 10 today. Network TV news coverage is also in retreat. According to Pew’s State of the News Media 2014 report, network coverage of foreign news in 2013 was less than half of what it was in the late 1980s.

NPR and the FT are among the news outlets that have added foreign bureaus since 2004

The legacy media story isn’t all bad news, though. The wire services are still alive and well, and outlets with a robust foreign presence have become more robust. The Associated Press (AP) maintains bureaus in 81 countries, while Bloomberg has correspondents in 73. NPR has added 13 bureaus abroad since 2004, and the Financial Times has added 10 during the same period. The Wall Street Journal has kept up a strong foreign presence, and Time and The Economist still have eight and 21 bureaus, respectively.

The New York Times continues to expand its global footprint, reopening an Istanbul bureau, launching bureaus in Warsaw and Tunis, hiring a contract correspondent in Tehran. Due in part to its merger with the International Herald Tribune, the Times has 75 foreign correspondents, a historic high, and 31 bureaus, seven more than it had 10 years ago. Readers are hungry for global coverage, says Michael Slackman, a former Times Cairo correspondent who is now the international managing editor, and the shrinkage of overseas news in other major U.S. papers has given the Times all the more reason to boost its foreign coverage.

But legacy media face a challenge from newcomers chasing a younger demographic and loaded with cash. Pew found that 30 of the largest digital-only news organizations account for about 3,000 jobs, and one significant area of investment is global coverage. The Huffington Post hopes to grow to 15 countries from 11 this year. Quartz has reporters in London, Bangkok, Delhi, and Hong Kong. In December 2013, Vice Media co-founder Shane Smith committed $50 million to a new venture, Vice News, which now has 34 bureaus around the world and has produced a series of remarkable—and sometimes controversial—documentaries.

In early 2013 Vice’s filmmakers accompanied former Chicago Bulls star Dennis Rodman on a trip into authoritarian North Korea, where Rodman engaged in a bizarre round of “basketball diplomacy” with the country’s leader Kim Jong-un and later praised the dictator as “a great guy.” A five-part documentary, “The Islamic State,” by veteran filmmaker Medyan Dairieh, provided an unprecedented look at life inside the ISIS stronghold in Raqqa. In both cases the filmmakers had the kind of access that most media can only dream about, but Vice also came under fire for giving two of the world’s most horrendous regimes a popular platform.

That’s hardly to say that Vice specializes in puffery. In April 2014 gunmen seized Vice correspondent Simon Ostrovsky in the separatist enclave of Slovyansk in eastern Ukraine, where he had been producing a series of hard-hitting reports on the conflict called “Russian Roulette: The Invasion of Ukraine.” Ostrovsky was interrogated and held for three days.

Kevin Sutcliffe, Vice’s head of news programming in Europe, says mainstream TV networks wrongly assumed young people weren’t interested in foreign news. The problem “was the worn-out approach, with newscasters, tight packages, and live feeds from Washington. The world is a rough, raggedy place, and young people want journalism that reflects that. They want authentic close-up reporting, less packaging, less mediation.” Vice News has racked up more than 160 million video views and has one million YouTube subscribers, evidence, Sutcliffe says, that the 30-and-under crowd will flock to foreign news if it’s delivered in an edgy and immersive way.

He shrugs off criticism that many of Vice’s documentaries lack context and promote their millennial reporters over their subject matter, and says he’s proud of the Rodman-in-North-Korea and life-in-the-Islamic-State stories. “Those pieces got enormous notice and provoked discussion,” says Sutcliffe. “You come away with indelible and extraordinary images that give you insight into what’s going on there.”

BuzzFeed has 175 million unique visitors a month and enough venture capital to take a run at the journalistic establishment. In July 2013, BuzzFeed hired Miriam Elder, a former Moscow bureau chief for The Guardian, to build a foreign-bureau system from the ground up. Elder has hired full-time reporters in Istanbul, Nairobi, Kiev, and Cairo, as well as correspondents who report exclusively on women’s rights and international lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) issues. “There’s a huge activist community in the USA, and our thinking was, ‘This is a natural audience for us, and [an international beat reporter] is a great way to get them interested in other countries,” says Elder, who’s planning to hire reporters to cover China and Mexico.

It’s typical of the ways in which BuzzFeed has sought to differentiate itself from legacy media. “The younger generation is getting their news through Facebook, Twitter,” Elder says, “so every story we write has to be breaking news.” The formula so far is working. A $50 million investment from the Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz will help Elder grow her correspondent corps.

Jonah Peretti, BuzzFeed’s founder and CEO, says he’s building a global media brand and sees foreign news as essential, a view that aligns him with such old-school media moguls as Henry Luce. Though BuzzFeed’s primary audience is between 18 and 34, Peretti insists, “Our investment is for a global audience of all ages. We do [foreign news] because it matters to readers and can have a big impact on the world. … BuzzFeed has figured out a business model to support journalism. We have the resources to invest in foreign reporting, investigative journalism, narrative features, and beat reporting.”

BuzzFeed’s foreign reportage has been sophisticated and informative. Recent standout work includes Middle East correspondent Mike Giglio’s lengthy report from the Syria-Turkey border on the illicit oil trade that is enriching ISIS, and Max Seddon’s piece about how the rebels in Donetsk, Ukraine were quietly creating the trappings of an independent state. “BuzzFeed is our competition now,” the Times’s Slackman says. “We’d be foolish not to take them seriously.”

How is BuzzFeed getting it right? Mostly by marrying a reputation for hipness and irreverence with smart hiring. Elder has brought aboard half a dozen reporters with formidable expertise in the subjects they’re covering, such as Gregory D. Johnsen, their inaugural Michael Hastings National Security Fellow, who wrote a well-received book about Islamic extremism in the Middle East, “The Last Refuge: Yemen, al-Qaeda, and America’s War in Arabia.”

Still, not all of BuzzFeed’s journalism would pass muster at more established news organizations. A recent piece, by Mike Giglio, purporting to be an exclusive interview with a man who has smuggled ISIS fighters into Europe, was pieced together largely from a single unnamed source, with a handful of pro forma denials, a method not regarded as best journalism practice.

Most of the new digital start-ups don’t have the advantage of BuzzFeed’s huge bankroll. GlobalPost, founded in 2008 by Charles Sennott, a former Boston Globe Middle East correspondent, and Philip Balboni, a Boston cable TV executive, set out to replicate, on a low budget, the foreign correspondent corps of American newspapers in their heyday. The site put a dozen marquee reporters on retainer, but much of its reporting has been provided by young American freelancers, who are paid a few hundred dollars per story. (I signed on as a contributor to GlobalPost early on, but pulled out when I realized I didn’t have the time and the pay was low.) As a business venture, GlobalPost has struggled. “We have not yet reached break even,” says Balboni, GlobalPost’s president and CEO.

Lately, Sennott has scaled back his involvement to develop a nonprofit venture called The GroundTruth Project, which relies on grants and focuses on training locals in some of the world’s hot spots to do in-depth reporting. Sennott has worked with a group of international editors, journalists, and advocacy groups, such as the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Reporters Without Borders, and the Frontline Club of London, to draft a new set of shared expectations and responsibilities for news organizations and field correspondents—whether staff or freelance or local hires.

Shared standards would be timely since the rising demand for freelancers has its perils. Before the spate of kidnappings and killings of journalists in Syria, it was common for media organizations to rely on freelancers in war zones and send them on assignments without proper insurance and training, says Farnaz Fassihi, a Beirut-based staffer for The Wall Street Journal. The pay was low, competition was fierce, and they often took “crazy risks,” according to Fassihi, to distinguish themselves from the pack. That practice is less common in Syria now, she adds.

In Syria, more than 80 journalists have been kidnapped—with about 20 still missing—and at least 70 journalists, nearly half of them freelancers, have been killed since 2011, according to the CPJ. The vast majority of those killed were Syrians. Seven, including freelancers Foley and Sotloff, were Americans or Europeans working for Western news organizations.

Ayman Oghanna, an Istanbul-based freelance war photographer for Al Jazeera America, says that in 2012, he made a vow never to go into Syria without having an assignment and his insurance covered. “Not many media were willing to give me that,” he says. “A number of prestigious magazines said, ‘Go in, and when you’re out of danger we’ll take what you have.’” Oghanna was outraged by the failure of these publications to assume responsibility for him, but he knew plenty of other freelancers who were willing to accept those terms.

Foley had been freelancing for GlobalPost and Agence France-Presse before he crossed the border into Syria in the fall of 2012. AFP global news director Michèle Léridon says Foley was not on assignment for the agency, but he would “propose images to us when he thought he had something interesting to file. We did not discuss movements with him, and we never asked him to go to any particular area.”

GlobalPost maintained a closer relationship with Foley, but Balboni stresses that he went into Syria on his own after rejecting Balboni’s offer of a staff job in South America. Once he was inside Syria, GlobalPost’s editors took his stories. “We’ve been reflecting on this question [of Foley’s kidnapping] every day. There’s a lot we need to learn from this,” says Sennott, who points out that GlobalPost made certain that Foley took a hazardous environments training course before traveling to the Middle East. “We mounted an extraordinary effort” to locate Foley and obtain his release, Balboni insists. “We had people on the border within a week. They went into Syria, and they investigated for months. We spared no expense, no effort.” A video showing Foley’s beheading was released in August. ISIS said it killed Foley in retaliation for U.S. airstrikes in Iraq.

The abductions and killings of journalists in Syria have ushered in a new era of caution

Kathleen Carroll, executive editor of the Associated Press, says her agency never uses freelancers unless they’ve been vetted and have insurance and protective gear, and won’t send them to Syria or Libya. “Plenty of journalists go out on the branch until the branch is cracked, and our job is to pull them back,” she says. “We owe them that. To say ‘I trust their judgment’ is a complete abdication of responsibility.”

In November 2013, Agence France-Presse decided that it, too, would no longer accept photos or any other contributions from freelancers who travel into rebel-held Syria, though it would continue to use material provided by Syrian nationals.

The Foley and Sotloff nightmares have prompted a reckoning in the new media world. BuzzFeed’s Elder says the company keeps a security adviser on retainer and has turned down recent requests from Giglio to travel into Syria. When he worked along the border on the oil story, Giglio stayed in continual contact with the home office and had his movements tracked by a GPS device. “We are always assessing and reassessing the risks,” says Elder.

Organizations are springing up to provide the institutional support freelancers need. Storyhunter, a Brooklyn-based organization founded in 2012 that works with freelance overseas journalists, provides its members with medical insurance through April International, a company also used by Reporters Without Borders.

Away from the conflict zones, some freelancers are thriving. Kathleen McLaughlin has contributed from Beijing since 2006 to The Economist, GlobalPost, BuzzFeed, and Women’s Wear Daily. She often finances her travel in China through grants and works in media ranging from video to long-form narrative. There’s no question, she believes, that freelancers fill an essential role. “There is a misconception that people work as freelancers because they can’t do anything else,” says McLaughlin. “It’s exactly the opposite. Once you figure out how to make a living at it, you can do anything.”

So how can such work be supported, especially in crisis zones? One way is for news organizations to underwrite the cost of risk and hazardous environment training, and pay freelancers a day rate that allows them to buy insurance. Foreign correspondents are more vulnerable than ever, in part because they are no longer regarded as indispensable channels of information to the public. “The bad guys don’t need foreign correspondents anymore because organizations like ISIS can now get their message out directly,” Carroll notes.

It’s not only the bad guys who are bypassing the mainstream media. Citizen journalism reached a critical mass during President Bashar al-Assad’s vicious crackdown on pro-democracy protests in Syria in 2011. “The international media could not go to Syria, because [the government] blocked off all the visas,” says NPR’s Amos, who has covered Syria since the conflict began. Many of these young Syrian activists were influenced by the bloody events in 1982 in Hama, where President Hafez al-Assad’s regime put down a rebellion by the Muslim Brotherhood by killing between 10,000 and 30,000 people. “These young Syrians said, ‘This time there will be pictures. This time people will know what happened here,’” Amos says. Western governments started sending iPhones and cameras, set up Internet links, and created radio stations along the border. The result: “Some Syrians gradually morphed into actual professional journalists, and they’re very good at it,” according to Amos.

Outlets for citizen journalists are expanding. GuardianWitness and Global Voices enable citizens to tell their own stories, with a focus on foreign news. The Guardian also holds training programs in places like Delhi and Johannesburg to encourage locals to do reporting. Citizen journalism fills an important need, but the reporting often lacks the analysis and context that experienced journalists provide.

Citizen journalists and advocacy organizations are among the new players covering foreign news

Other nontraditional players have gotten into the business, too. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees fields a team of a dozen journalists to produce multimedia stories about Syrian refugees, Iraqis displaced by ISIS, and other victims of the Middle East conflict. The work has appeared on The New Yorker, Time, The Atlantic, and The Guardian websites as well as Mashable and BuzzFeed.

Peter Bouckaert, emergencies director for Human Rights Watch (HRW), travels to crisis zones that mainstream media rarely visit, contributing to Foreign Policy, The Washington Post, and The Telegraph as well as to HRW’s own reports. He and a HRW colleague have made 12 lengthy trips to the war-torn Central African Republic in the past 18 months. With its donor contributions, HRW has been able to operate largely free of the financial considerations that constrain news outlets. “When I tell correspondents what kind of resources I draw on, they end up very jealous,” Bouckaert says.

But is the agenda-driven reporting by these organizations really news or just another form of PR, albeit for worthy causes? Bouckaert argues that the difference between HRW’s work and foreign correspondence is negligible: “We’re trying to draw attention to international crises and hold the perpetrators responsible. Objectivity and impartiality are important for us, and lots of journalists want to make a difference in these places as well.”

The days when big-city newspapers nurtured a bond of trust between readers and experienced correspondents have given way to a more haphazard, fluid environment. Some see danger in that. “We’re losing the mature, in-depth reporting about what’s happening in more remote places of the world,” says Bouckaert. “The reflective reporting that is done by experienced journalists with resources behind them is rapidly disappearing. And it’s not being replaced by Vice. I consider that to be self-centered journalism. It’s ‘Look at the crazy shit I’ve been up to’ rather than drawing attention to horrific suffering.”

Others give new media ventures their blessing. “We can’t afford to be too snooty about anyone who’s trying to engage people about what’s going on in the world,” says the AP’s Carroll. “If we can rid the profession of the castor oil tendency—‘Read this. It’s good for you’—that’s good.”

Correspondents have traditionally provided us with an education, albeit sometimes flawed, about the real world. Despite all of the challenges, the reporters are there. Now we need to find a way to protect and pay them.