A woman holds a candle at a prayer protest calling for an end to drug-related killings in Manila in November 2017

On what seemed like an ordinary work day in February, Filipino journalist Pia Ranada, who covers President Rodrigo Duterte, arrived at Malacañang Palace for a routine press briefing. A guard told her she was no longer allowed inside the compound. With her mobile phone, Ranada videotaped the interaction as she showed her press credentials and asked the guard from the Presidential Security Group (PSG) a series of questions. He tried to block the camera with his hand but Ranada held on.

The 27-year-old reporter for Rappler, a leading digital news outlet, where I am editor at large, says her hands were shaking when she composed her first tweet about the incident. However, she acted on what her editors burned into her memory: to chronicle any form of harassment or attempts to block access to Rappler’s beats. “But more than that,” Ranada says, “I felt that it was a newsworthy event and something the public needed to know about.” (That day Ranada was allowed into a briefing in the New Executive Building.)

Ranada’s ban from the presidential palace is just one example of the Filipino government’s intimidation and threats against the media. Despite the obstacles, though, independent Filipino news outlets are continuing to do vital work in an increasingly hostile environment.

Harry Roque, the president’s spokesman, said Duterte himself ordered the ban, likening Ranada to a “rude” guest: “If your guest is rude to you in your own home, can you blame it if the rude visitor is told to leave? It’s the same with the president.”

Ranada’s ban from the presidential palace is just one example of the Filipino government’s intimidation and threats against the media

Reporters Without Borders called the government’s decision a “serious violation of media freedom” and the Manila-based Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) said in a statement: “The message [of Malacañang] is clear. It is that journalists can and will be prevented from doing their jobs should they, like Ms. Ranada, ask government officials the tough questions … to get at the truth and to hold the powerful to account.” The Office of the President has since expanded the ban to all events where Duterte is a speaker. In March, Ranada was barred from covering the president’s speech to a group of entrepreneurs in Manila.

In addition to publicly criticizing journalists like Ranada and their work, Duterte has threatened media businesspeople like the Rufino-Prieto family, owners of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, who are negotiating the sale of the leading daily to Ramon Ang, a wealthy businessman close to the president. The largest TV network, ABS-CBN, is on edge as Duterte has vowed to block the renewal of its franchise, which expires during his term in office. Duterte does not regard press freedom as a right guaranteed by the Constitution. Press freedom “is a privilege in a democratic state,” he said in an interview with reporters in January. “You have overused and abused that privilege in the guise of press freedom.”

A climate of fear is present because of the thousands who have died due to the extrajudicial killings Duterte has ordered as part of his deadly drug war. Official figures as of March show that at least 4,000 suspected drug users have been killed in police operations. But the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates, an NGO, says the figure could be more than 12,000. The Philippines has repeatedly appeared in the global impunity index of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), ranking 5th in 2017. More than 40 journalists have been killed in the past decade, mostly in the provinces, away from the eyes of the national media.

Maria Ressa, right, CEO of Rappler, an online news agency, addresses a rally of Philippine journalists and supporters in Quezon City as they protest the recent Securities and Exchange Commission's revocation of its registration in January

Congress is dominated by Duterte’s allies. On May 11, Supreme Court Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, a Duterte critic, was ousted from office after the government petitioned for her removal. Duterte himself has threatened to abolish the Commission on Human Rights, which spoke up against the killing of suspected drug users. He subsequently said the threat was made in jest. He ordered the suspension of a ranking official of the Ombudsman, a state agency on the frontlines of fighting corruption in government, which probed the president’s finances.

The Philippines has also been confronting the phenomenon of “fake news” since the presidential election campaign in 2016. Duterte’s campaign used social media to spread false stories—such as Pope Francis praising Duterte and Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong endorsing his candidacy—and to attack his rivals. “Divisive campaigning happened in the Philippines six months before it happened in the U.S.,” says Clarissa David, a professor at the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication. “The problem is disinformation. … In this country, the focus of disinformation campaigns has been on attacking political personalities. Very often the content’s tone is angry, a lot of it designed to outrage and to make the public emotional. This appeal to emotions is what is polarizing.”

A case in point: In May of last year, Mocha Uson, assistant secretary in the Presidential Communications Operations Office, shared on her Facebook page a photo of soldiers, kneeling as they prepared to battle terrorists in Marawi City in Mindanao, southern Philippines. She called for the public to support the soldiers. A Twitter account, supposedly run by members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, showed that the photograph was, in fact, of Honduran police in 2015 calling on God to stop violence in Honduras, according to an English translation of the original post.

More than 40 journalists have been killed in the past decade, mostly in the provinces, away from the eyes of the national media

In February, as the Philippines was commemorating the 32nd anniversary of the people power revolt that ousted dictator Ferdinand Marcos, Uson conducted a poll among her followers. Her question: “Was the 1986 people power revolt a product of fake news?” Eighty-six percent replied yes. What the country is seeing now is a “normal continuation of the campaign,” says Randy David, sociology professor at the University of the Philippines and a columnist for the Philippine Daily Inquirer who has been critical of Duterte.

Another factor, according to Jonathan Corpus Ong of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and Jason Cabañes of the University of Leeds in the U.K., is the involvement of advertising and public relations professionals as “architects of disinformation.” Ong and Cabañes conducted a 12-month study of “fake news” and “troll armies” in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election. Ong and Cabañes interviewed operators of fake accounts on Facebook and Twitter and the “strategists”—advertising and PR gurus at agencies by day who often also freelance for outside clients, including political campaigns—who provided the scripted narratives. The researchers recommend setting up a “self-regulatory commission” to require disclosure of political consultancies as a way to stop the spread of divisive and false information.

Seminars on media literacy—particularly on fighting disinformation—are gaining traction, especially among young people. In February, the Philippine Daily Inquirer, Rappler, online newsmagazine Vera Files, and the ABS-CBN News Channel got together with CMFR, bloggers, academics and Media Nation, a civil-society project that convenes journalists to discuss the industry and its problems, in a two-day seminar on addressing misinformation. Many in the audience were students from leading universities, including the communication departments of Ateneo de Manila University and De La Salle University and the journalism department of the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication.

Since last year, the Philippine Press Institute (PPI), an organization of national and community newspapers, has connected with seven universities through day-long seminars on spotting “fake news.” “We want the students to think and analyze,” says PPI’s training director Tess Bacalla. “We provide examples to make them see the pattern, that government machinery is being used to peddle fake news.” PPI’s most recent session was in March at the Universidad de Manila. “I learned to be more picky about the things I share on my social media accounts,” says Harley Jefferson Dimaano, a 19-year-old communications student. He says the seminar was an eye-opener. “I can now spot fake news.” He checks accounts to verify sourcing and, if he determines a post is fake, he clicks the report button on the social media platform.

The Philippine Press Institute has put on seminars at several universities in the last year about spotting "fake news"

At Vera Files, a group of journalists, mostly women, work in a small rented room in an old building in suburban Quezon City, fact-checking Duterte. The U.S.-based National Endowment for Democracy has been funding Vera Files’ fact-checking project through a grant since 2016. The site’s 2017 year-ender video shows Duterte speaking before his communications group, admonishing them to tell the truth. Cut to the next scene: a TV interview in which Duterte admits falsely accusing his fierce critic, Senator Antonio Trillanes, of having overseas bank accounts.

Vera Files also conducts workshops on fact-checking and fighting fake news at universities around the country, often with the PPI. Ellen Tordesillas, who heads Vera Files, gives a short talk on how to spot fake news, the importance of primary sources, and the need for fact-checking, while other speakers describe how journalists work, the process of vetting sources, and the strict ethical guidelines that are followed.

Other news organizations are getting involved, too. A leading TV network, GMA, has started an online show called “Fact or Fake,” calling attention to false reports posted on dubious websites and shared thousands of times. In a recent episode, “Fact or Fake” showed that a news report claiming that Duterte was immune from prosecution by the International Criminal Court—which is investigating extra- extra-judicial killings in his war on drugs—is fake. The report quoted a supposed international law expert from Oxford College and the accompanying photograph was of a German politician.

At least six Philippine media companies and organizations are led by women. They include ABS-CBN, GMA, The Philippine Star, Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, Vera Files, and Rappler. A recent study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies shows that women have occupied around 40 percent of management positions in the private sector over the last 15 years. But women are still under-represented in the Cabinet, Congress, and local elective offices.

“We have to deal with fakery and falsity on many fronts. We have to stay the course, stand our ground. We have to report and make sense of the continuing narrative for others. We have to tell the story” —Rosario Garcellano, Philippine Daily Inquirer opinion editor

In addition to the attacks from the government, online hate messages against individual journalists are common. Jodesz Gavilan, 24, joined Rappler fresh out of university and was able to experience journalism before Duterte. President Benigno Aquino, Duterte’s predecessor, “just resorted to calling out the press to be fair but these often faded away since he didn’t have a massive troll army to echo his every cry,” she says.

Today, Gavilan, who covers human rights issues and NGOs, says, “The threats are misogynistic in nature most of the time. They’ve threatened violence, such as rape and murder, warning me to shut up lest I want to be part of the numbers killed in Duterte’s drug war.” When she is able to confirm that the sources are not trolls, she does her own sleuthing and reports offensive accounts to employers and schools. In an effort to educate the public about threats to the media, Rappler has produced a short video featuring six journalists—two from television, two from news websites, one freelance photographer, and one foreign correspondent—who share similar experiences.

Rappler itself continues to report, despite the fact that in January, the Securities and Exchange Commission, a regulatory body, revoked the site’s license to operate, alleging that it has foreign owners, in violation of the Philippine Constitution. Rappler is 100 percent owned by Filipinos. The site is operating while the case is on appeal. Since the decision to shut down Rappler, journalists and civil-society groups have organized Black Friday protests in various venues, including universities.

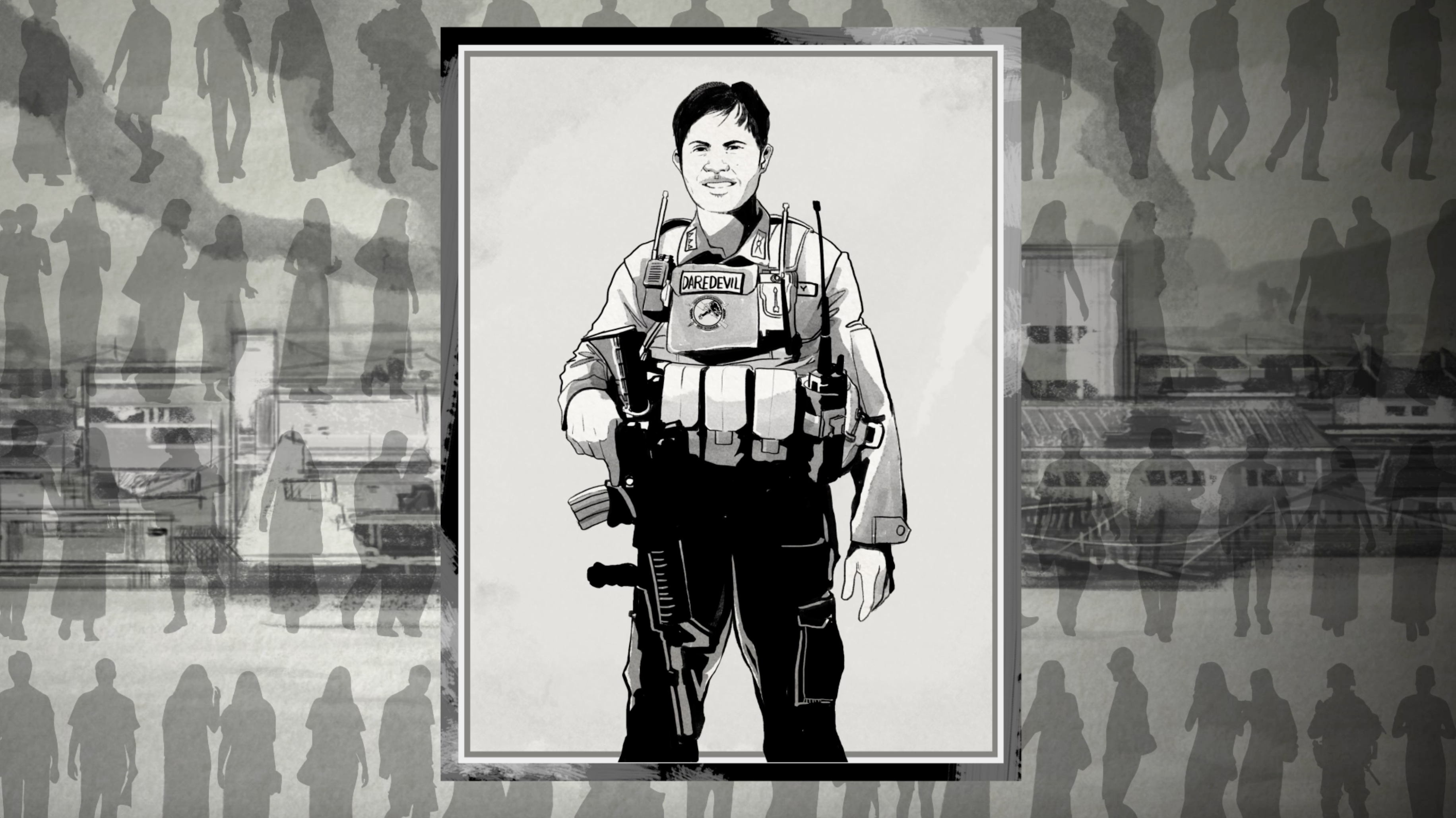

And Rappler’s work goes well beyond covering Duterte. The site experiments with new forms of storytelling, using animation and 360-degree video to report on the war against terrorists in Marawi. The animation focused on a soldier who died saving one of his troops, while the virtual-reality documentary placed viewers amid the ruins of the war zone.

Rappler is also forging partnerships with government and civil-society groups. Agos, a Filipino word that means flow, is the site’s long-running campaign for disaster preparedness. Typhoons regularly strike the Philippines, and Agos produces content on how to mitigate risks during disasters. “Government agencies still tap us to help them in popularizing drills,” says Gemma Bagayaua-Mendoza, head of research. “We activate our volunteers every time there is an impending weather disturbance or a humanitarian crisis. Last year, we introduced a new dashboard that could help us efficiently route verified critical-incident reports to groups that can respond on the ground.”

Another initiative, #NotOnMyWatch, was a nine-month project with the Department of Interior and Local Government and various local government units. Rappler created an online platform through which members of the public could report evidence of government corruption. According to Bagayaua-Mendoza, over 4,500 citizen reports were gathered, while the social media campaign reached a total of 16 million users on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and the website. Though few reports were referred to government—whistle-blowers were reluctant to be identified—“What we did then was use the reports as leads for stories, both for investigative reporting and to educate the public on typical scams in government,” says Bagayaua-Mendoza.

At the Philippine Daily Inquirer, which has a fierce history of holding public officials accountable, things are uncertain as the owners, the Rufino-Prieto family, conclude the sale of the newspaper to the president’s ally Ang. “There is no pressure to be less assertive and to self-censor, but any astute reporter will sense that there is something different in the newsroom,” a longtime staff member says. Stories about sensitive topics, like the International Criminal Court complaint against Duterte and the president’s finances, are toned down and those linking him to corruption seem to be off-limits, according to one staff member who requested not to be identified. In the past, human-rights and corruption issues were front-page stories. Under Duterte, these have been buried in the inside pages.

In addition to the attacks from the government, online hate messages against individual journalists are common

So far, the op-ed section remains feisty. Columnists who have been critical of Duterte have remained. “I was not told that certain columnists or regular contributors of commentaries would have to go,” says Rosario Garcellano, editor of the opinion pages. “I take care, now more than ever, that our ‘fearless views’ mantra is reflected in a mix of views for and against the government, although criticism often takes up much of the content.” John Nery, who writes an opinion column and some of the editorials, says, “We have to fight for the newspaper we believe in.” This thought has kept him and some of his colleagues going.

Garcellano was a journalist during the martial law years under Ferdinand Marcos. When she was a John S. Knight fellow at Stanford University in the late 1980s, she remembers telling her colleagues “how hard we struggled to keep our heads—and integrity—above water. I also recall saying that I merely lost a job at the onset of martial law, but others lost their lives.” Today, she says, times are similarly difficult but “vastly different” because “we have to deal with fakery and falsity on many fronts. We have to stay the course, stand our ground. We have to report and make sense of the continuing narrative for others. We have to tell the story.”

That conviction seems to be shared by the next generation of Filipino journalists. When in January Rappler’s Ranada was asked by the young editors of Scout, a print and online magazine for youths, what they can do to uphold press freedom, she replied: “You can help just by speaking up … being critical of government propaganda. … This is our generation’s fight, the fight of millennials. This fight is not just about Rappler. It’s a fight for the ideals we strive for, that any freedom-loving citizen should strive for.”