Imagine a country where reporters shy away from contentious issues, where journalism is considered a dead-end job, where the private sector rarely advertises through mass media, and where the mainstream press wields virtually no power in national affairs.

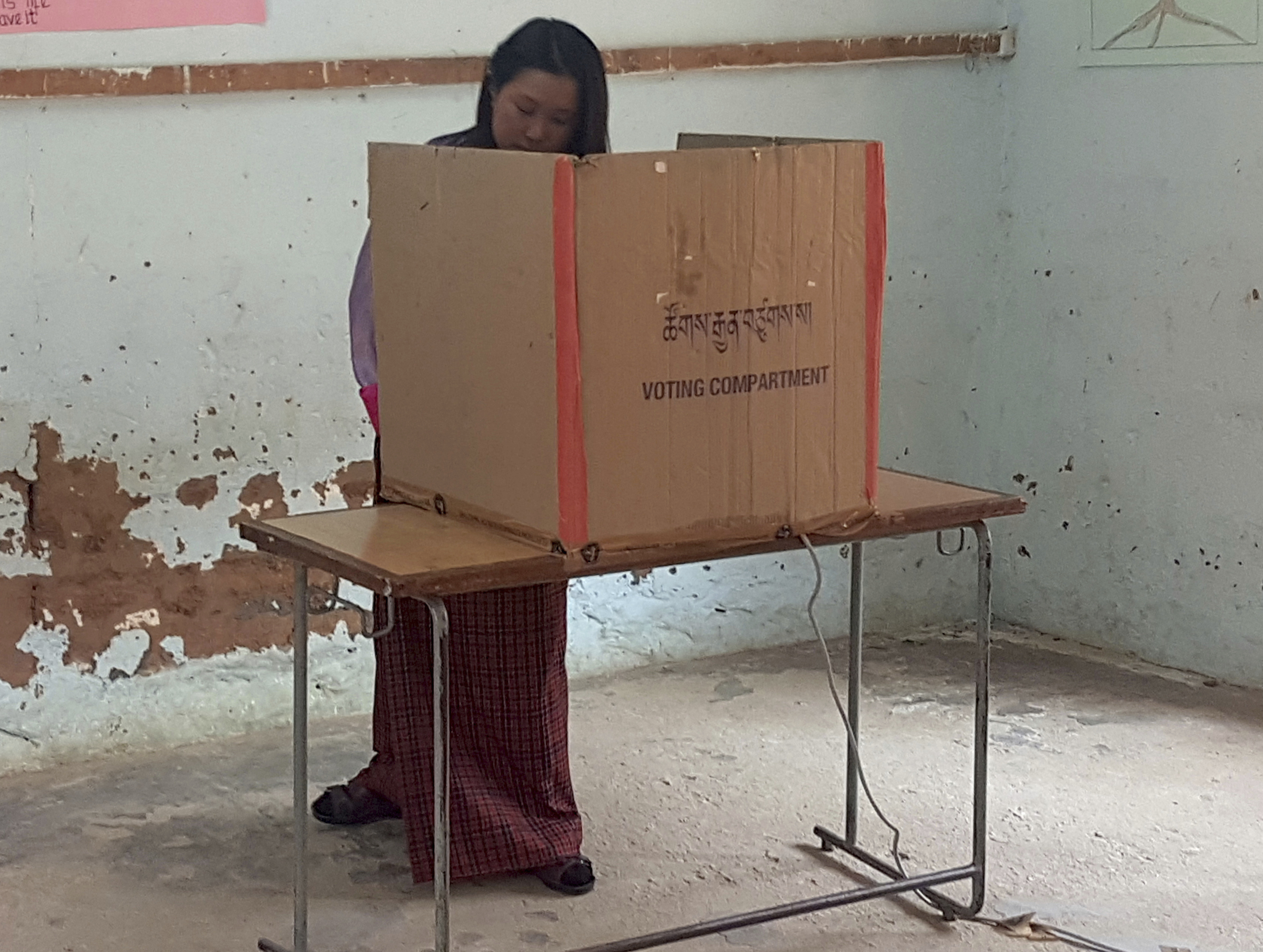

That country is the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan—one of the world’s youngest democracies and the home of a governing policy known as Gross National Happiness, or GNH. But the dismal state of its Fourth Estate may be about to change. With the surprise victory in the October 18 national elections of the young and progressive Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT)—roughly translated, the Bhutan Togetherness Party—a rare window of opportunity has opened for the nation’s struggling media.

During the fall of 2017, I made an extended reporting trip to Bhutan, my third since 2012. As part of my research, I spoke with leading journalists, to understand the country’s singular media landscape—one that defies the idealized image of this popular tourist destination. Among ecologists, left-leaning economists, and spiritual seekers, Bhutan is seen as an enlightened model, known for its carbon-negative environmental stewardship, a GNH philosophy that purports to spurn capitalistic excess, and a gentle society that outwardly presents a respite from the frenetic pace of the West.

In reality, Bhutan is a nation in breathtaking, and often painful, transition. And the country’s journalists have not fully addressed the challenges. The 2018 World Press Freedom Index from Reporters Without Borders described the Bhutanese media with this headline: “Stifling Self-Censorship.” A 2014 survey by the Journalists Association of Bhutan (JAB) found that 71 percent of working journalists felt that the profession had lost its attraction, 66 percent said it was difficult to access public information, and 58 percent felt “unsafe” covering critical stories, fearing reprisal.

The Bhutanese press was not always so anemic. In 2006, Bhutan’s revered Fourth King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, set in motion the end of the nation’s absolute monarchy and its replacement with a parliamentary democracy. That year, two private publications, Bhutan Times and Bhutan Observer, joined the government-owned Kuensel, until then the country’s only newspaper. As Tenzing Lamsang, current editor of The Bhutanese newspaper, recalled in a 2015 story, the new media players had brought “a more critical and investigative journalism, or what we in Bhutan like to call ‘controversial articles.’” Over the next few years, more private newspapers sprung up, confronting the status quo.

By the time Bhutan’s first national elections took place, in 2008, a cadre of young but seasoned reporters was prepared for its watchdog role. Press freedom was at its peak, and the country was a model in South Asia, with more than 300 reporters covering their beats. By 2010, 12 newspapers were energizing the public conversation.

“We were full of zeal and enthusiasm,” Needrup Zangpo, former editor of the Bhutan Observer, told me. “There was a sense of competition. All of us pushed boundaries. We took advantage of the newfound freedom.” The results were impressive: exposés on government land scams, substandard airport runway construction, the country’s draconian Tobacco Act that criminalized smoking (the policy was ultimately changed because of the media’s outcry), and other investigations.

Even Bhutan’s GNH brand was portrayed through a skeptical lens. In 2009, Bhutan Observer reporter Rabi Dahal tagged along with officials from the Gross National Happiness Commission as they toured remote mountain villages. The most recent national census (in 2005) had found that an improbable 96.8 percent of Bhutanese considered themselves “happy” or “very happy.” Dahal’s reporting proved otherwise. After the officials had extracted obediently upbeat assessments from the villagers and completed their surveys, Dahal returned to the villagers’ homes and asked them to describe the realities of their lives. “I convinced them that I wasn’t a zhungi dasho”—a decorated government official—“but a newspaper man,” he wrote, with evident pride at the presumed equivalence in prestige.

In an award-winning article titled “Ungar Diary,” Dahal elaborated: “[T]he truth is, they aren’t happy. They suffer a food shortage for at least six months in a year. Many of them are indebted to financial institutions. An old woman told me that she couldn’t pay off her debt, even if she ‘piled life upon life.’ Marauding wild animals ravage their crops every season, leaving them with little.” In that precious interlude of press freedom, journalists were respected and confided in—and they operated as independent truth-tellers, just as Bhutan’s Fourth King had envisioned when he liberalized the media a few years earlier.

In 2012, when an economic crisis struck Bhutan, the press was disproportionately hurt. Government advertising dwindled and was diverted to ministry websites—a catastrophe for print media, because 90 percent of newspaper ads come from the government. Newspapers had to lay off staff, delay wages, and otherwise cut costs, and scores of veteran writers and editors left the field.

Today, fewer than 100 reporters and editors, most of them inexperienced, cover the entire country. Kuensel reporters earn about $230 per month, reporters for independent papers about $160. The slack has been taken up by social media (nearly 100 percent of Bhutanese have cellular access, and one-third of the population is on Facebook). Like everywhere else, however, its web agora mixes facts and informed opinion with speculation and venom, often in anonymous posts.

Intertwined with these economic binds is a pervasive self-silencing among Bhutanese journalists—a restraint that, to those accustomed to the West’s clamorous and combative press, seems almost inconceivable, an inside-out version of our own. Part of this reticence is the strong affiliative pull of Bhutan’s “small society syndrome”: Never offend others, for fear of sowing discord, personal recrimination, or—the worst fate of all—social ostracism. As Namgay Zam, a gutsy and widely followed independent multimedia journalist and activist told The Diplomat in 2017, “Journalists are afraid to report, imagining perceived consequences. Because it’s such a small society, you don’t know whose shoes you’re treading on.”

The result is a daily news feed that largely rehashes press releases and offers anodyne coverage of conferences, meetings, official visits, and cultural programs. Kinley Dorji, the first editor of Kuensel and the doyen of Bhutanese reporters, conceded in a Bhutan Dialogues TV forum in October 2017, “The media is, I think, a little bit lost.”

Why does this matter? Because this fledgling democracy still has a chance to live up to its GNH ideals. “A free press will mean that we will have what one scholar called ‘mass mediated democracy’—whether you are talking about raising public discourse on important issues, reporting without fear, giving voice to the people who are not able to speak up for themselves,” Gopilal Acharya, the founder of The Journalist, a newspaper devoted to investigative journalism, politics, and the economy, told me last fall. (A haven for long-form reportage, that publication also, alas, went under.) “That is one of the major roles that media plays in our part of the world: giving voice to the voiceless.”

Many issues need airing. Unchecked rural-to-urban migration is crushing the fragile capital of Thimphu. Bhutan is grappling with joblessness among youth, and concomitantly rising rates of drug abuse and suicide. It has seen widening economic disparities, as Western materialism seeps into the cultural fabric. In September 2017, a man murdered his wife by setting her on fire in Thimphu’s Coronation Centennial Park, with no passersby willing to help—a heinous crime and civic non-response almost unimaginable in this devout Buddhist culture. That same summer, Bhutan’s northwest Doklam region was the site of a tense military standoff between the country’s two behemoth border neighbors—India to the south and China to the north. Most of these troubling trends are perfunctorily covered in the media.

Bhutan is a tiny country, and seemingly off the map in the current headline mix. Why should the West care—consumed as it is by a torrential news cycle and by the Trump administration’s relentless attacks on the media?

The day after Bhutan’s national elections, I put this question to Namgay Zam. “The very fact that the Western press cares about democracy and everyone's stake in it should make Bhutan a country of interest to them,” she responded in an email. “Two journalists to date, including myself, have been sued for libel—[and] these suits end up curtailing the independence of journalism. If the media, especially Western media that has the most powerful voice globally, is not interested in the emerging voices of journalism in countries like Bhutan, then there is no hope for a free and fair press. My greatest fear is that democracy will fail.”

I also put the question to Needrup Zangpo, who in addition to having led the Bhutan Observer served as executive director of JAB. His nuanced answer reflected Bhutan’s journalistic ambitions as well as its deep roots in the values of social harmony and Buddhism’s Middle Path. “Serious journalists here view the newly revitalized press in America as a new wave of journalism practice,” he wrote. But he added a caveat: “The Western press can do more than perpetuate the cesspool of controversies and finger-pointing. That's when Bhutan would be relevant to them. Here's a quiet group of people trying to do things, including journalism and democracy, differently. If Bhutan's democracy succeeds, the West will have a refreshing brand of democracy they can be proud of [for] a long time.”

Now that Bhutan’s politics have shifted, will its journalists be revived? In its manifesto, DNT pledged to “strengthen the Bhutanese news media and extend necessary support to media organizations.” How would the country’s press corps choose to flesh out that promise?

Recently, Needrup Zangpo took over as executive director of the Bhutan Media Foundation (BMF), which was established in 2010 through a royal charter by the Fifth King, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, to foster the growth of “free, independent, responsible and credible media.” Zangpo would like to see full printing subsidies for newspapers and government advertising guidelines that would support high-caliber private media. He says that the West can offer specific assistance in the form of scholarships, professional training and workshops, and financial support to such organizations as BMF and JAB.

Namgay Zam hopes that the Bhutan Broadcasting Service, the state-owned TV and radio broadcaster, will be converted into an independent, publicly funded entity with government support mandated by law, like the BBC. “This is the only way to ensure the national broadcaster remains non-politicized,” she said. “The government can also take a strong stand against editorial interference, making it compulsory that none of the members of Parliament or the opposition interfere.” Further down the line, many reporters want to see passage of the Right to Information Act, which was drafted in 2007 but never enacted by Parliament; the law would ease access to public information and make government more accountable.

All of those proposals are a tall order for a country with a 2017 GDP of $2.5 billion—precisely the same as the 2017 GDP of Lewiston, Idaho.

I met with Zangpo—a tall, sturdy man with a measured demeanor—last fall, in the JAB offices. Out his window, dominating the hilly skyline, glinted the giant gilt statue of Shakyamuni at Buddha Point. Near the end of our conversation, Zangpo’s cell phone came to life—not with the local ring tone, but with “Thrungthrung Karmoi Luzhey": the song of the black-necked crane. A haunting melody composed by a lama, it was played by Zangpo himself, on a bamboo flute that he had carved.

A sacred icon in Bhutan, this majestic bird is deemed by international conservation groups a “vulnerable” species: in peril of becoming “endangered” unless the circumstances that threaten its survival improve. Bhutan’s mainstream media is likewise struggling in a difficult habitat. Can we save it from journalism’s endangered list?

That country is the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan—one of the world’s youngest democracies and the home of a governing policy known as Gross National Happiness, or GNH. But the dismal state of its Fourth Estate may be about to change. With the surprise victory in the October 18 national elections of the young and progressive Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT)—roughly translated, the Bhutan Togetherness Party—a rare window of opportunity has opened for the nation’s struggling media.

During the fall of 2017, I made an extended reporting trip to Bhutan, my third since 2012. As part of my research, I spoke with leading journalists, to understand the country’s singular media landscape—one that defies the idealized image of this popular tourist destination. Among ecologists, left-leaning economists, and spiritual seekers, Bhutan is seen as an enlightened model, known for its carbon-negative environmental stewardship, a GNH philosophy that purports to spurn capitalistic excess, and a gentle society that outwardly presents a respite from the frenetic pace of the West.

In reality, Bhutan is a nation in breathtaking, and often painful, transition. And the country’s journalists have not fully addressed the challenges. The 2018 World Press Freedom Index from Reporters Without Borders described the Bhutanese media with this headline: “Stifling Self-Censorship.” A 2014 survey by the Journalists Association of Bhutan (JAB) found that 71 percent of working journalists felt that the profession had lost its attraction, 66 percent said it was difficult to access public information, and 58 percent felt “unsafe” covering critical stories, fearing reprisal.

The Bhutanese press was not always so anemic. In 2006, Bhutan’s revered Fourth King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, set in motion the end of the nation’s absolute monarchy and its replacement with a parliamentary democracy. That year, two private publications, Bhutan Times and Bhutan Observer, joined the government-owned Kuensel, until then the country’s only newspaper. As Tenzing Lamsang, current editor of The Bhutanese newspaper, recalled in a 2015 story, the new media players had brought “a more critical and investigative journalism, or what we in Bhutan like to call ‘controversial articles.’” Over the next few years, more private newspapers sprung up, confronting the status quo.

By the time Bhutan’s first national elections took place, in 2008, a cadre of young but seasoned reporters was prepared for its watchdog role. Press freedom was at its peak, and the country was a model in South Asia, with more than 300 reporters covering their beats. By 2010, 12 newspapers were energizing the public conversation.

“We were full of zeal and enthusiasm,” Needrup Zangpo, former editor of the Bhutan Observer, told me. “There was a sense of competition. All of us pushed boundaries. We took advantage of the newfound freedom.” The results were impressive: exposés on government land scams, substandard airport runway construction, the country’s draconian Tobacco Act that criminalized smoking (the policy was ultimately changed because of the media’s outcry), and other investigations.

Even Bhutan’s GNH brand was portrayed through a skeptical lens. In 2009, Bhutan Observer reporter Rabi Dahal tagged along with officials from the Gross National Happiness Commission as they toured remote mountain villages. The most recent national census (in 2005) had found that an improbable 96.8 percent of Bhutanese considered themselves “happy” or “very happy.” Dahal’s reporting proved otherwise. After the officials had extracted obediently upbeat assessments from the villagers and completed their surveys, Dahal returned to the villagers’ homes and asked them to describe the realities of their lives. “I convinced them that I wasn’t a zhungi dasho”—a decorated government official—“but a newspaper man,” he wrote, with evident pride at the presumed equivalence in prestige.

In an award-winning article titled “Ungar Diary,” Dahal elaborated: “[T]he truth is, they aren’t happy. They suffer a food shortage for at least six months in a year. Many of them are indebted to financial institutions. An old woman told me that she couldn’t pay off her debt, even if she ‘piled life upon life.’ Marauding wild animals ravage their crops every season, leaving them with little.” In that precious interlude of press freedom, journalists were respected and confided in—and they operated as independent truth-tellers, just as Bhutan’s Fourth King had envisioned when he liberalized the media a few years earlier.

In 2012, when an economic crisis struck Bhutan, the press was disproportionately hurt. Government advertising dwindled and was diverted to ministry websites—a catastrophe for print media, because 90 percent of newspaper ads come from the government. Newspapers had to lay off staff, delay wages, and otherwise cut costs, and scores of veteran writers and editors left the field.

Today, fewer than 100 reporters and editors, most of them inexperienced, cover the entire country. Kuensel reporters earn about $230 per month, reporters for independent papers about $160. The slack has been taken up by social media (nearly 100 percent of Bhutanese have cellular access, and one-third of the population is on Facebook). Like everywhere else, however, its web agora mixes facts and informed opinion with speculation and venom, often in anonymous posts.

Intertwined with these economic binds is a pervasive self-silencing among Bhutanese journalists—a restraint that, to those accustomed to the West’s clamorous and combative press, seems almost inconceivable, an inside-out version of our own. Part of this reticence is the strong affiliative pull of Bhutan’s “small society syndrome”: Never offend others, for fear of sowing discord, personal recrimination, or—the worst fate of all—social ostracism. As Namgay Zam, a gutsy and widely followed independent multimedia journalist and activist told The Diplomat in 2017, “Journalists are afraid to report, imagining perceived consequences. Because it’s such a small society, you don’t know whose shoes you’re treading on.”

The result is a daily news feed that largely rehashes press releases and offers anodyne coverage of conferences, meetings, official visits, and cultural programs. Kinley Dorji, the first editor of Kuensel and the doyen of Bhutanese reporters, conceded in a Bhutan Dialogues TV forum in October 2017, “The media is, I think, a little bit lost.”

Why does this matter? Because this fledgling democracy still has a chance to live up to its GNH ideals. “A free press will mean that we will have what one scholar called ‘mass mediated democracy’—whether you are talking about raising public discourse on important issues, reporting without fear, giving voice to the people who are not able to speak up for themselves,” Gopilal Acharya, the founder of The Journalist, a newspaper devoted to investigative journalism, politics, and the economy, told me last fall. (A haven for long-form reportage, that publication also, alas, went under.) “That is one of the major roles that media plays in our part of the world: giving voice to the voiceless.”

Many issues need airing. Unchecked rural-to-urban migration is crushing the fragile capital of Thimphu. Bhutan is grappling with joblessness among youth, and concomitantly rising rates of drug abuse and suicide. It has seen widening economic disparities, as Western materialism seeps into the cultural fabric. In September 2017, a man murdered his wife by setting her on fire in Thimphu’s Coronation Centennial Park, with no passersby willing to help—a heinous crime and civic non-response almost unimaginable in this devout Buddhist culture. That same summer, Bhutan’s northwest Doklam region was the site of a tense military standoff between the country’s two behemoth border neighbors—India to the south and China to the north. Most of these troubling trends are perfunctorily covered in the media.

Bhutan is a tiny country, and seemingly off the map in the current headline mix. Why should the West care—consumed as it is by a torrential news cycle and by the Trump administration’s relentless attacks on the media?

The day after Bhutan’s national elections, I put this question to Namgay Zam. “The very fact that the Western press cares about democracy and everyone's stake in it should make Bhutan a country of interest to them,” she responded in an email. “Two journalists to date, including myself, have been sued for libel—[and] these suits end up curtailing the independence of journalism. If the media, especially Western media that has the most powerful voice globally, is not interested in the emerging voices of journalism in countries like Bhutan, then there is no hope for a free and fair press. My greatest fear is that democracy will fail.”

I also put the question to Needrup Zangpo, who in addition to having led the Bhutan Observer served as executive director of JAB. His nuanced answer reflected Bhutan’s journalistic ambitions as well as its deep roots in the values of social harmony and Buddhism’s Middle Path. “Serious journalists here view the newly revitalized press in America as a new wave of journalism practice,” he wrote. But he added a caveat: “The Western press can do more than perpetuate the cesspool of controversies and finger-pointing. That's when Bhutan would be relevant to them. Here's a quiet group of people trying to do things, including journalism and democracy, differently. If Bhutan's democracy succeeds, the West will have a refreshing brand of democracy they can be proud of [for] a long time.”

Now that Bhutan’s politics have shifted, will its journalists be revived? In its manifesto, DNT pledged to “strengthen the Bhutanese news media and extend necessary support to media organizations.” How would the country’s press corps choose to flesh out that promise?

Recently, Needrup Zangpo took over as executive director of the Bhutan Media Foundation (BMF), which was established in 2010 through a royal charter by the Fifth King, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, to foster the growth of “free, independent, responsible and credible media.” Zangpo would like to see full printing subsidies for newspapers and government advertising guidelines that would support high-caliber private media. He says that the West can offer specific assistance in the form of scholarships, professional training and workshops, and financial support to such organizations as BMF and JAB.

Namgay Zam hopes that the Bhutan Broadcasting Service, the state-owned TV and radio broadcaster, will be converted into an independent, publicly funded entity with government support mandated by law, like the BBC. “This is the only way to ensure the national broadcaster remains non-politicized,” she said. “The government can also take a strong stand against editorial interference, making it compulsory that none of the members of Parliament or the opposition interfere.” Further down the line, many reporters want to see passage of the Right to Information Act, which was drafted in 2007 but never enacted by Parliament; the law would ease access to public information and make government more accountable.

All of those proposals are a tall order for a country with a 2017 GDP of $2.5 billion—precisely the same as the 2017 GDP of Lewiston, Idaho.

I met with Zangpo—a tall, sturdy man with a measured demeanor—last fall, in the JAB offices. Out his window, dominating the hilly skyline, glinted the giant gilt statue of Shakyamuni at Buddha Point. Near the end of our conversation, Zangpo’s cell phone came to life—not with the local ring tone, but with “Thrungthrung Karmoi Luzhey": the song of the black-necked crane. A haunting melody composed by a lama, it was played by Zangpo himself, on a bamboo flute that he had carved.

A sacred icon in Bhutan, this majestic bird is deemed by international conservation groups a “vulnerable” species: in peril of becoming “endangered” unless the circumstances that threaten its survival improve. Bhutan’s mainstream media is likewise struggling in a difficult habitat. Can we save it from journalism’s endangered list?