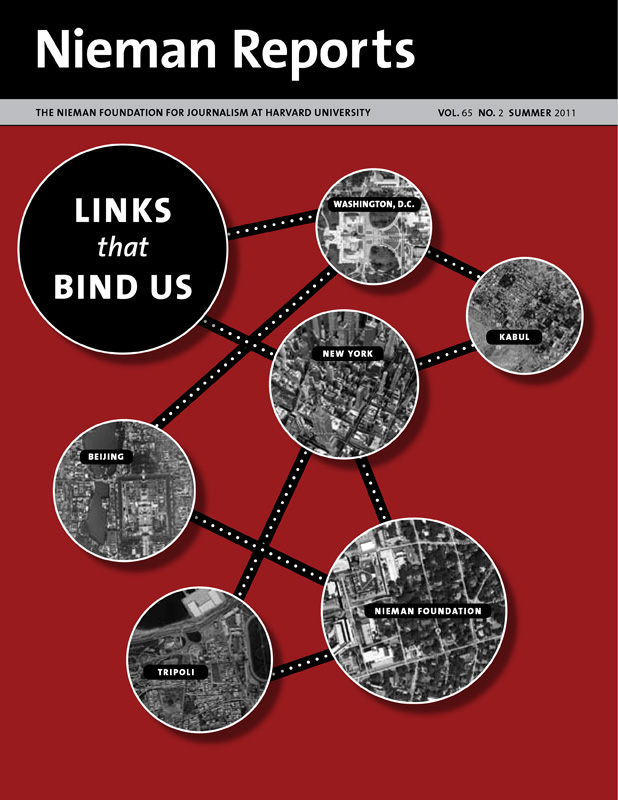

Links that Bind Us

In digital space, journalists are proving to be a powerful force in creating, nurturing and engaging communities. No longer serving only geographic zones, they confront the fragmentation of audience and the need to attract and retain “eyeballs.” Their efforts to embrace and interact with communities are fueled by an instinct to survive. Habits and hobbies, interests and values, political leanings, and sports allegiances are the grist of community formation. Discover the various roles journalists are assuming and how the links we share bind us.

As filmmaker in residence at an inner-city hospital, Katerina Cizek worked as a storytelling partner with health workers and patients.

I encountered journalism on the day I came to understand the word "community."

It was my first assignment as a student photojournalist and I was behind the barricades in Quebec at what became known as the Oka Crisis. It was the summer of 1990, and the news media were watching the military showdown between the Canadian armed forces and a Mohawk community.

The confrontation involved plans to expand a municipal golf course onto an ancient Mohawk burial ground. This standoff, which some consider Canada's Wounded Knee, lasted two and a half months. When it was over, so much had changed, including the political balance between First Nations and the federal government.

As the day turned to dusk, it was clear that I would remain at the standoff through the night. A few members of the Mohawk Warrior Society had pulled up plastic lawn chairs around a rabbit-eared television directly behind the barricade of overturned police vehicles and large branches. They were watching the evening news. They invited me to join them, and when I did I saw that Alanis Obomsawin, a First Nations Abenaki documentary filmmaker, was there to document this crisis through her own eyes for the National Film Board of Canada.

One hundred meters down the road and behind the barricades, military guns were aimed in the community's direction and ready to be fired. Army helicopters buzzed above. Like the military, the Warriors had weapons. But there were unarmed women and children present as well.

As I watched TV with the Warriors, I came to realize how divergent the mainstream representation of this armed conflict was from what I was witnessing. That evening I heard about unresolved land claims and the abuse of power through the centuries as non-Natives encroached on First Nations lands. There were among the mainstream media some well-established members who expressed views about this mistreatment—a view I shared. Later, they were accused of Stockholm syndrome.

That evening I became committed to and certain of the value of the independent and community-centered making of media. During the intervening decades a tsunami of this kind of storytelling became central to the digital democratization of media. But for me that night crystallized the connections among media making and democracy, journalism and documentary, citizenship and community.

Digital Media and Community

Taking place, as my epiphany did, at the dawn of digital media, I became aware early on of its revolutionary potential.

A few months later, in March 1991, TV viewers in Los Angeles had witnessed one of the first modern acts of citizen journalism. When George Holliday heard police sirens and a commotion outside his bedroom window, he went to the balcony of his high-rise building with his new hand-held video camera and filmed the confrontation going on 90 feet below. He recorded for almost eight minutes as four white Los Angeles police officers brutally beat Rodney King, a black man.

The one minute of Holliday's footage broadcast on local TV and then on news shows throughout the world sparked a "handicam revolution." More than a decade later, a documentary that I co-directed with Peter Wintonick featured the use of that footage, its impact and legacy, and the political impetus to use digital video to document human rights abuses. Called "Seeing is Believing: Handicams, Human Rights and the News," it challenged the authorial voice of mainstream media in the face of rising community-based media and the digital revolution. The film was broadcast throughout the world and is used today in classrooms and human rights advocacy training.

Fast-forward to now, and I am at the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada. (Obomsawin, still making films and approaching 80, is my colleague.) I am working to refine and redefine the documentary filmmaking process and think about notions of representation and emerging technology—all with community and the potential of digital citizenship uppermost in mind. What I do happens at the confluence of these issues; my goal is not only to document what I find, but also to locate our place as documentarians in all of this, a subject that has preoccupied me for 20 years.

Storytelling—Inside Out

At the NFB, I've been as likely to be found in the hallways of an inner-city hospital as in an elevator at a residential high-rise building—places, if I'm honest, I would rather not be. But these are the physical spaces where I have had to be to connect communities of people who are rarely heard from or seen with our unlikely forms of storytelling and media making. It is in these new forms of storytelling that I believe we are creating frames for engaging with some of the most important topics of the 21st century.

For my first four years at the NFB, as I worked with veteran producer Gerry Flahive, I was a filmmaker in residence at an inner-city hospital. Like my approach to covering the Oka Crisis, the perspective I took with this project was unconventional. I examined, in part, how the media and members of the medical community might work together to create new forms of intervention. Could telling a story improve someone's health?

I worked in partnership with health workers, patients and researchers; the key ingredient was respect for our editorial independence and differing expertise. Usually, a film made inside a hospital would be about what happens to workers and patients. I approached making films with them, not about them, with the goal of effecting tangible change in the social and political realms. The seven projects we did there, including "NFB: Filmmaker in Residence," an interactive documentary that won a Webby, dealt with the transformative potential that exists at the intersection of digital media, health care, and community.

Now I'm in another kind of building in the second year of Highrise, another NFB media project. Our notions of what I call "interventionist media" are now transposed from a hospital into a different community ecosystem—the high-rise, which is the most commonly built form during the last century. Such buildings and their inhabitants, especially residential ones, have been, at best, ignored, and, at worst, vilified as being the cause of civil unrest that is often characterized as racial or ethnic.

As I did at the Oka barricade and in the hospital, I am bypassing the predictable, often sensational headlines to explore the profound ways that digital storytelling can be a force for political mediation. For me as a filmmaker, the high-rise building becomes a metaphor for density, and it offers a frame through which to think about sweeping issues of migration and globalization, urbanity and community.

In this century, more than any other, to be human is to be urban. Yet politicians, journalists and academics have only a meager understanding of what people's lives are like in such places. News can't simply be about what happens in the financial district of a city's downtown core when some of the most significant stories are unfolding in our urban peripheries. There, the neglected and pressing needs of vulnerable communities are found along with stark evidence of economic injustice. Amid the concrete, I find inspiration for change.

.jpg)

The online documentary “Out My Window” is a virtual high-rise, with each window on the screen leading into a story about the life of a resident in a different city.

'Out My Window'

I constructed my first global interactive online Highrise documentary, "Out My Window," as a virtual high-rise. Each apartment window in the building is a digital portal to a different city. Once inside, the user enters the life of a high-rise resident through first-person storytelling and thousands of images.

Using Skype, e-mail and Facebook, I got in touch with photographers, activists and journalists in mid-sized cities—such as Prague, Beirut and Toronto—which are representative of the places where most urban dwellers live. From 13 cities and in 13 languages, 100 contributors shared more than 90 minutes of stories about living in these urban environments.

"Out My Window" is about high-rise residents harnessing the power of community, music and art in their search for meaning in the space they inhabit, prefabricated as it might be. People renew what was old and crumbling as they repurpose waste into things useful and even beautiful. They create—and recreate—community in spite of the built forms surrounding them.

This Web documentary has garnered global attention, including a 2011 digital Emmy in the nonfiction category. It is spawning conversations on blogs and on Twitter. In short, "Out My Window" gave the Highrise project the initial push we wanted with its ability to engage in dialogue people who are too often separated into silos of interest, whether in architecture or city planning, journalism or human rights, education or housing activism. And it has spurred conversation among the residents themselves.

Questions We Ask

What lies ahead—at both a global and local level—is the desire to push the boundaries of what's possible at the places where community and documentary intersect. In another iteration of the Highrise project, we've been working for quite some time with residents of a high-rise building to arrive at a sense of the values shared among those who live in the isolating spaces of a tall residential building. Here are a few questions animating our efforts:

- What aspects of these people's lives would conventional journalism and documentary filmmaking usually miss?

- What more can we learn by collaborating with members of the community as they help us, as media makers, get closer to what's happening?

- What about the stories and images that residents create themselves?

- How can we support the self-representation of those who live in the high-rise as we want to hear from people in their voices and see them through their images?

- How can the act of media making support community building?

One overarching question involves trying to learn more about how notions of community take on wholly new meanings in digital space. As this happens, what is the role of the journalist as documentarian? A key ingredient is what happens with technology—with what it enables all of us, as makers of media, to do. Then there is also the evolving idea of "digital citizenship." This addresses our level of access to technology and our ability to use and harness the power of technology to engage and transform the world we live in.

What is undeniable is the tightening relationship between communications technologies and political activism. Exploding with the Rodney King video, this political linkage is seen now in the role social media are playing in the uprisings across the Arab world. From the quieter gestures of photo-bloggers in a meeting room behind the elevator in a suburban Toronto high-rise, digital citizenship is continuing to shape the ways in which community and journalism come together to tell important stories of our time.

Katerina Cizek is a documentary director with the National Film Board of Canada. Her recent project "Highrise: Out My Window" won a 2011 digital Emmy.