Iran: Can Its Stories Be Told?

Journalists — Iranians and Westerners — share their firsthand experiences as they write about the challenges they confront in gathering and distributing news and information about Iran and its people. Their words and images offer a rare blend of insights about journalists’ lives and work in Iran. In the fifth part of our 21st Century Muckrakers series about investigative and watchdog reporting, the focus turns to coverage of issues involving public health, safety and trust. And in Words & Reflections, essays touch on objectivity, religion, blogging, Ireland and post 9/11 America.

When a private attorney asked the school board of a small district on Long Island, New York, to put him on the payroll so he could get a pension and benefits, board members approved it without giving it a second thought. He assured them it was perfectly legal and that other people were doing it. “It wasn’t a big deal,” recalled former board member Lorraine Deller.

Little did these school board members realize that in making that seemingly innocuous decision in 1978, they set the stage for a scandal that would explode 30 years later on the front page of Long Island’s major newspaper, Newsday. In fact, the discovery of what had become a routine practice that bilked taxpayers of millions of dollars set off a cascade of investigative stories, federal and state inquiries, landmark pension reform in the legislature, and the return of more than $3.4 million to state coffers, along with tens of millions more in savings to taxpayers once these illegal pensions were stopped.

The unearthing of these hidden deals—and the financial consequences they held for taxpayers—was a story very well suited to a newspaper. Within a year from when our reporting began, Newsday had published nearly 100 stories, columns and editorials about aspects of what, by then, had become a large and costly network of stakeholders profiting from this arrangement. The kind of sustained commitment Newsday made to telling this story is rarely found in broadcast media or on the Web, and unfortunately it’s becoming scarcer, too, at many newspapers as resources for investigative coverage shrink.

As this story built, outraged readers became engaged by contributing to it; their tips helped to drive the narrative. As momentum built, news of what we’d uncovered spread throughout the state of New York and to other parts of the country. It was an exciting and exhausting ride and a reminder to those of us involved that newspapers occupy a singular niche in American journalism.

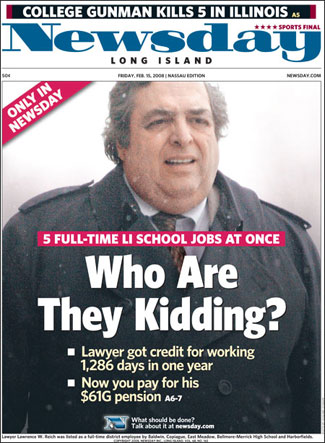

Newsday’s story on Lawrence Reich.

Uncovering Public Corruption

The trailhead of our reporting effort was marked—as many great investigative stories are—by a tip. A reader was angered by stories I’d written about spending abuses in special districts, the tiny units of local governance that handle services like water hookups and garbage pickups in specific areas. Such districts can be found throughout the country, but they are often overlooked by reporters because they are so small. Though small, the magnitude of the abuse was great. That is precisely why they made such a good subject for investigation. Such special districts cost taxpayers nearly $500 million a year on Long Island alone.

Figuring all of this out, however, was not easy. Investigative reporting never is. It took months, for example, to get district payrolls, because no one had ever asked for them before. Once in hand, they showed wildly inflated salaries and benefits for jobs often held by a tight circle of political insiders. In one district, a meter reader was being paid $93,000. In another, two ditch-diggers made more than $100,000 a year. On top of those salaries were gold-plated health benefits, the kind rarely provided to workers in the private sector.

The reader who’d called with the tip said a private attorney, who was paid as a consultant, was placed on a school district payroll so that he could secure a guaranteed pension and health benefits. Public records showed the tip was right but even worse than he thought. Through my Freedom of Information Act requests for records from the state, county and school districts that employed him, I obtained a wide range of information—from the attorney’s pension history to his time sheets. These documents filled an entire file drawer. Getting the records from school board officials, who were loath to release them, took time and required frequent follow-up phone calls and, in some cases, formal appeals when requests were denied.

Within weeks of gaining all of these records, the full story emerged. Five school districts—at the same time—had falsely reported that the attorney, Lawrence Reich, was a full-time employee, while also paying his law firm $2.5 million in legal fees. As a result, Reich retired with a pension of nearly $62,000 and free health benefits for life. Then he returned to work for the districts as a consultant. The abuse was so flagrant that he was credited with working 1,286 days in a single year, according to records. What upset our readers the most was that state auditors knew about the arrangement—which is barred by the Internal Revenue Service—yet did nothing to stop it.

Reich agreed to be interviewed and defended the arrangement as common practice, but he did not agree to be photographed. So we assigned one of our photographers to watch his home and office; eventually we got a shot of him in his office parking lot. He wasn’t aware that he had been photographed until his picture ran on the cover of Newsday with the headline, “Who are they kidding?”

One of Newsday’s “double dippers.”

Readers Respond, Legislators, Too

Newsday’s front-page story set off a firestorm. Readers were furious. The FBI and IRS subpoenaed the school districts’ records the next day, and New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo launched a parallel investigation days later.

My colleague, Eden Laikin, then joined me. Often we worked evenings and on weekends. Our challenge was to break new ground with each investigative piece as we kept up with fast-breaking news developments. The story built its own momentum, which helped ratchet up pressure on officials, who were feeling the heat from constituents.

Shortly after Eden began working with me, many of our newsroom colleagues, including a longtime editor who had helped shepherd the Reich story into print, left. Economic pressures had forced Newsday to make painful cuts in staff and news hole. Fortunately for us, however, Newsday remained committed to the story.

Within weeks, it became clear that Reich’s arrangement was not an isolated one. Records showed that 23 school districts—or nearly one-fifth of those on Long Island—had improperly reported their attorneys as employees, entitling them to good-sized benefit packages. This prompted New York Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli to launch a review of every attorney on a public payroll statewide. Meanwhile, Cuomo’s investigators were expanding their probe statewide—netting, among others, the brother and sister-in-law of a top state judge.

All of this investigative action by public officials meant that we had to move fast simply to not be beaten on what had been our story. The pace was daunting. We requested more records, including vendor records and payments to all professionals employed by 124 school districts and 96 villages, meeting minutes, Civil Service records, and pension databases from the state’s two largest retirement systems, among others. We built our own databases, as well.

After prodding from readers, we also decided to write about a different kind of pension abuse, one that stunned the public with its scope and cost. At least 40 Long Island school administrators were “double dippers,” meaning they had retired and then returned to work as so-called interim employees. Pension and payroll records showed that they were paid six-figure paychecks on top of equally lucrative pensions, collectively reaping at least $11 million a year.

We found one superintendent collecting a pension of $316,245 and returning to work as a superintendent for an additional $200,000. Another superintendent, convicted of stealing more than $2.2 million from his school district, was collecting a pension of $173,495 in prison. In several cases, administrators literally retired one day and returned the next day to the same job. These double dippers had turned a system meant to provide security in retirement to one that minted millionaires once they turned 55.

Our stories hit a nerve. Newspapers throughout the state, as well as national law journals, picked up on our reporting. In New York, like everywhere else these days, there is a growing divide between the public and private sectors, as public-sector salaries have risen and private-sector benefits are disappearing. On Long Island, the average public-sector worker makes $10,000 a year more than the average private-sector worker and gets a guaranteed pension and health benefits on top of that. Taxpayer resentment runs deep.

Readers deluged state legislators with letters and e-mails, and a rare public hearing on the issue resulted. Although the New York legislature has been branded as “dysfunctional” by some, the clamor was too much to ignore. In June 2008, the legislature unanimously passed sweeping pension reforms. The state’s comptroller and the education department revamped their rules and beefed up enforcement. A few months later, state officials and legislators proposed an additional reform measure to address abuses in special districts. By year’s end, New York’s attorney general and comptroller had reached settlements involving more than 75 lawyers and other professionals and recovered more than $3.4 million. In addition, the state has saved tens of millions more in pensions no longer being paid.

For those of us who reported these stories, the most gratifying part was our newspaper’s willingness to stick with the story in spite of enormous economic challenges—Newsday was sold last year by the Tribune Company, which has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection—and pressures from people we were writing about. These are tumultuous and frightening times for newspapers, but this kind of reporting is what we do best. And, more than ever, it’s the kind of reporting that we must continue to do.

Sandra Peddie is an investigative reporter at Newsday, a daily newspaper on Long Island, New York. She and her colleague, Eden Laikin, won the 2009 Selden Ring Award for Investigative Reporting for their stories on special district and pension abuses.

Little did these school board members realize that in making that seemingly innocuous decision in 1978, they set the stage for a scandal that would explode 30 years later on the front page of Long Island’s major newspaper, Newsday. In fact, the discovery of what had become a routine practice that bilked taxpayers of millions of dollars set off a cascade of investigative stories, federal and state inquiries, landmark pension reform in the legislature, and the return of more than $3.4 million to state coffers, along with tens of millions more in savings to taxpayers once these illegal pensions were stopped.

The unearthing of these hidden deals—and the financial consequences they held for taxpayers—was a story very well suited to a newspaper. Within a year from when our reporting began, Newsday had published nearly 100 stories, columns and editorials about aspects of what, by then, had become a large and costly network of stakeholders profiting from this arrangement. The kind of sustained commitment Newsday made to telling this story is rarely found in broadcast media or on the Web, and unfortunately it’s becoming scarcer, too, at many newspapers as resources for investigative coverage shrink.

As this story built, outraged readers became engaged by contributing to it; their tips helped to drive the narrative. As momentum built, news of what we’d uncovered spread throughout the state of New York and to other parts of the country. It was an exciting and exhausting ride and a reminder to those of us involved that newspapers occupy a singular niche in American journalism.

Newsday’s story on Lawrence Reich.

Uncovering Public Corruption

The trailhead of our reporting effort was marked—as many great investigative stories are—by a tip. A reader was angered by stories I’d written about spending abuses in special districts, the tiny units of local governance that handle services like water hookups and garbage pickups in specific areas. Such districts can be found throughout the country, but they are often overlooked by reporters because they are so small. Though small, the magnitude of the abuse was great. That is precisely why they made such a good subject for investigation. Such special districts cost taxpayers nearly $500 million a year on Long Island alone.

Figuring all of this out, however, was not easy. Investigative reporting never is. It took months, for example, to get district payrolls, because no one had ever asked for them before. Once in hand, they showed wildly inflated salaries and benefits for jobs often held by a tight circle of political insiders. In one district, a meter reader was being paid $93,000. In another, two ditch-diggers made more than $100,000 a year. On top of those salaries were gold-plated health benefits, the kind rarely provided to workers in the private sector.

The reader who’d called with the tip said a private attorney, who was paid as a consultant, was placed on a school district payroll so that he could secure a guaranteed pension and health benefits. Public records showed the tip was right but even worse than he thought. Through my Freedom of Information Act requests for records from the state, county and school districts that employed him, I obtained a wide range of information—from the attorney’s pension history to his time sheets. These documents filled an entire file drawer. Getting the records from school board officials, who were loath to release them, took time and required frequent follow-up phone calls and, in some cases, formal appeals when requests were denied.

Within weeks of gaining all of these records, the full story emerged. Five school districts—at the same time—had falsely reported that the attorney, Lawrence Reich, was a full-time employee, while also paying his law firm $2.5 million in legal fees. As a result, Reich retired with a pension of nearly $62,000 and free health benefits for life. Then he returned to work for the districts as a consultant. The abuse was so flagrant that he was credited with working 1,286 days in a single year, according to records. What upset our readers the most was that state auditors knew about the arrangement—which is barred by the Internal Revenue Service—yet did nothing to stop it.

Reich agreed to be interviewed and defended the arrangement as common practice, but he did not agree to be photographed. So we assigned one of our photographers to watch his home and office; eventually we got a shot of him in his office parking lot. He wasn’t aware that he had been photographed until his picture ran on the cover of Newsday with the headline, “Who are they kidding?”

One of Newsday’s “double dippers.”

Readers Respond, Legislators, Too

Newsday’s front-page story set off a firestorm. Readers were furious. The FBI and IRS subpoenaed the school districts’ records the next day, and New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo launched a parallel investigation days later.

My colleague, Eden Laikin, then joined me. Often we worked evenings and on weekends. Our challenge was to break new ground with each investigative piece as we kept up with fast-breaking news developments. The story built its own momentum, which helped ratchet up pressure on officials, who were feeling the heat from constituents.

Shortly after Eden began working with me, many of our newsroom colleagues, including a longtime editor who had helped shepherd the Reich story into print, left. Economic pressures had forced Newsday to make painful cuts in staff and news hole. Fortunately for us, however, Newsday remained committed to the story.

Within weeks, it became clear that Reich’s arrangement was not an isolated one. Records showed that 23 school districts—or nearly one-fifth of those on Long Island—had improperly reported their attorneys as employees, entitling them to good-sized benefit packages. This prompted New York Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli to launch a review of every attorney on a public payroll statewide. Meanwhile, Cuomo’s investigators were expanding their probe statewide—netting, among others, the brother and sister-in-law of a top state judge.

All of this investigative action by public officials meant that we had to move fast simply to not be beaten on what had been our story. The pace was daunting. We requested more records, including vendor records and payments to all professionals employed by 124 school districts and 96 villages, meeting minutes, Civil Service records, and pension databases from the state’s two largest retirement systems, among others. We built our own databases, as well.

After prodding from readers, we also decided to write about a different kind of pension abuse, one that stunned the public with its scope and cost. At least 40 Long Island school administrators were “double dippers,” meaning they had retired and then returned to work as so-called interim employees. Pension and payroll records showed that they were paid six-figure paychecks on top of equally lucrative pensions, collectively reaping at least $11 million a year.

We found one superintendent collecting a pension of $316,245 and returning to work as a superintendent for an additional $200,000. Another superintendent, convicted of stealing more than $2.2 million from his school district, was collecting a pension of $173,495 in prison. In several cases, administrators literally retired one day and returned the next day to the same job. These double dippers had turned a system meant to provide security in retirement to one that minted millionaires once they turned 55.

Our stories hit a nerve. Newspapers throughout the state, as well as national law journals, picked up on our reporting. In New York, like everywhere else these days, there is a growing divide between the public and private sectors, as public-sector salaries have risen and private-sector benefits are disappearing. On Long Island, the average public-sector worker makes $10,000 a year more than the average private-sector worker and gets a guaranteed pension and health benefits on top of that. Taxpayer resentment runs deep.

Readers deluged state legislators with letters and e-mails, and a rare public hearing on the issue resulted. Although the New York legislature has been branded as “dysfunctional” by some, the clamor was too much to ignore. In June 2008, the legislature unanimously passed sweeping pension reforms. The state’s comptroller and the education department revamped their rules and beefed up enforcement. A few months later, state officials and legislators proposed an additional reform measure to address abuses in special districts. By year’s end, New York’s attorney general and comptroller had reached settlements involving more than 75 lawyers and other professionals and recovered more than $3.4 million. In addition, the state has saved tens of millions more in pensions no longer being paid.

For those of us who reported these stories, the most gratifying part was our newspaper’s willingness to stick with the story in spite of enormous economic challenges—Newsday was sold last year by the Tribune Company, which has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection—and pressures from people we were writing about. These are tumultuous and frightening times for newspapers, but this kind of reporting is what we do best. And, more than ever, it’s the kind of reporting that we must continue to do.

Sandra Peddie is an investigative reporter at Newsday, a daily newspaper on Long Island, New York. She and her colleague, Eden Laikin, won the 2009 Selden Ring Award for Investigative Reporting for their stories on special district and pension abuses.