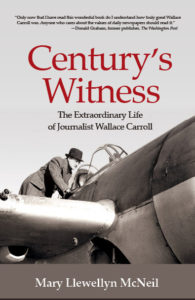

As a journalist for the United Press, Wallace Carroll reported on some of the 20th century’s most significant headlines. After covering the League of Nations for over a decade, Carroll took the post of UP’s London bureau chief at the start of World War II, where he oversaw coverage of the London Blitz. He became one of the first journalists to enter the Soviet Union after the Nazi invasion in 1941, and upon returning to the U.S., landed at Pearl Harbor just days after the attack. He would later take on roles at the Office of War Information, The New York Times, and the Winston-Salem Journal, where he helped earn the paper a Pulitzer. Yet despite these feats, Carroll has not garnered much modern-day name recognition. “Century’s Witness: The Extraordinary Life of Journalist Wallace Carroll,” written by Mary Llewellyn McNeil and set for publication by Whaler Books in September, sets out to tell the story of Carroll’s legacy.

In the following excerpt, McNeil describes Carroll’s views on objectivity, finding meaning in reporting, and journalism’s role in bolstering democracy:

In 1955 [Carroll] developed a theory he called the “tyranny of objectivity,” which he presented that year in a Nieman paper. The paper was most likely prompted by the rise of Joe McCarthy, in which Carroll believed the news media had been complicit. Objectivity, he believed, was a discipline that reporters, editors, and publishers impose upon themselves to keep their own feelings from affecting the presentation of the news. As such it seems a fine ideal. But to Carroll, its rigid and almost doctrinaire interpretation could lead to a lack of responsibility, or what he called the “objectivity” of the half-truth. Simply presenting both sides was not enough, he argued. Good reporting needed to add a third dimension — meaning. Reporters needed to dig down through the surface facts and fill in the background, interpret and analyze. He felt that McCarthy had been able to exploit the news media’s “objectivity” in printing what he’d said without analysis of whether it was true or not. He had made newspapers his accomplices in his reign of terror.

“I am sure,” Carroll wrote, “that if a scholarly study were made of the part played by American newspapers in the rise of Senator McCarthy, it would show that the Senator understood the deadly virtues of the American press much more clearly than we do ourselves. Such a study would show … [he] was able to exploit our rigid ‘objectivity,’ in such a way as to make the newspapers his accomplices.”

It seems an innocent example today, but believing that journalists had to be capable of interpreting the news as well as reporting it was the bedrock upon which journalists like [James] Reston and Carroll built their coverage, and it was still a relatively new idea in the early to mid-1950s. When a reporter had solid evidence that a statement was misleading, both felt, he had an obligation to report it. The overriding principle was that any practice that allowed newspapers to be “used” should be carefully scrutinized.

Carroll went on to describe three principles he adhered to: The first was to bring this third dimension of meaning to reporting on everything covered. The second was to find, train, and pay reporters who could do such three-dimensional reporting; and, finally, to be an editor and publisher who would back their reporters up with strong editing and protection from higher-ups who might be wanting to point coverage in a particular way. Overriding all of this, however, was his extraordinary attention to detail and an absolute commitment to accuracy, fairness, and finding out what was really going on. He demanded this from his reporters, and was always pushing them to do better, to be the best in the business. The aim of the reporter was to reach the highest common denominator of the mass audience, not the lowest.

Years later, when the technological revolution was taking place in the industry, he would reiterate the importance of every newspaper person to cultivate “a passionate interest in the meaning and the substance of the news, in the essential truth of what we print, in the relevance of that essential truth to the questions that the American reader will want to answer.” He warned of newspapers tendency to mirror their audience’s interests and tastes rather than to dig down to report on what he felt were the essential issues; the press’s responsibility was not to give their readers “a glittering mosaic of events” but rather a coherent and substantive picture.

Carroll also expressed his view of newspapers’ role in society. Good newspapers were needed in every town big enough to support them, he said, and what they should do is “hold up a mirror to the community so the people can see and understand the workings of a democratic society.” Papers needed to bring the outside world closer to their readers, to convey fascination and excitement of national and world affairs, “which give the reader a sense of participation in current history.” Papers should help their readers attain the “understanding they will require to become good citizens of their communities and of the nation and the world.” Newspaper careers, Carroll believed, proved the day’s greatest opportunity for community leaderships. Carroll had practiced what he preached in becoming executive editor of the Winston Salem Journal. In that, he believed, as did Gordon Gray [owner of the Winston-Salem Journal] “that journalism was about public service, and one that was vital to the nation.”

But also worth noting was the fun both Reston and Carroll saw in being a journalist. Neither could have imagined a better profession. In an article published in 1955, Carroll wrote that “the gathering, writing and editing of the news is hard, exacting work. It is done at times under severe pressure, and it may often involve the reporter, and his editor, in unpleasantness, hardship, and even danger…. Let all this be granted, but acknowledge that a good newspaperman is likely to fall asleep at night feeling a bit sorry for all those millions of men and women who are condemned to earn their living in ways that are drab and dreary.”