A reporter’s fateful question on March 31, 1954 led to the story that had more influence on my lifetime of science reporting than any other. The answer, symbolizing an age driven by science, ricocheted around the world the next day. It most likely influenced humanity’s almost immediate, unspoken decision that we would not blow ourselves up in a thermonuclear holocaust.

The occasion was the official public statement about the United States’ test of a 15-megaton hydrogen bomb on March 1, 1954, on the southern Pacific atoll of Bikini. A bomb using the hydrogen fusion process was a thousand times more powerful than an atom bomb. It had become a military reality less than nine years after America dropped the first two atomic bombs on Japan in August 1945.

A freshman at Harvard, I read the story on the front page of the April 1 New York Times in my college dorm.

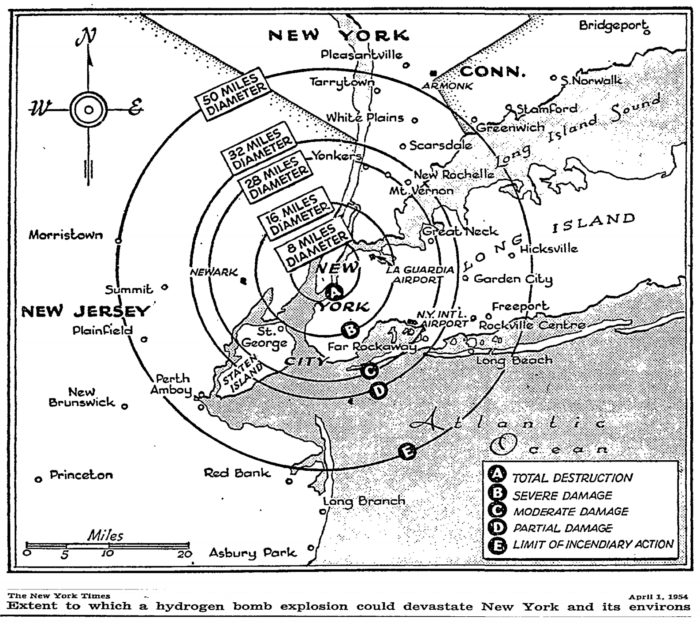

With President Dwight Eisenhower standing beside him, chairman Lewis Strauss of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission had been asked by a reporter: “What happens when the H-bomb goes off? How big is the area of destruction in its various stages?”

Strauss replied, “It can be made as large as you wish, as large as the military requirement demands, that is to say, an H-bomb can be made as large enough to take out a city.” The assembled reporters shouted, “What?” One of them asked, “How big a city?” Strauss replied, “Any city.” The questioner shot back, “Any city? New York?” Strauss said, “The metropolitan area, yes.”

People knew of the test already, because the unexpectedly large release of radiation had forced evacuation of neighboring atolls. But now the whole world could sense the scale of the threat and recoil from it, eventually demanding—in the Test Ban Treaty of 1963—cessation of all tests of nuclear explosives in the air, the oceans, and space.

A good case can be made that the stark picture Strauss painted for reporters helped humanity decide that the job was not to win a duel with clouds of H-bombs but rather to survive on humanity’s only platform, Earth.

H-Bomb Can Wipe Out Any City, Strauss Reports After Tests

By William L. Laurence

The New York Times, April 1, 1954

Excerpt

WASHINGTON, March 31—The United States can now build a hydrogen bomb big enough to destroy any city.

In revealing this today, Rear Admiral Lewis L. Strauss, chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, hinted that such a bomb could be delivered by plane.

The bomb tested at the Eniwetok proving grounds on March 1, Admiral Strauss announced, provided a “stupendous blast in the megaton range.” He said it was “double that of the calculated estimate.” A megaton is equivalent to 1,000,000 tons of TNT.

The explosive power attained in the test was reported by a member of the Joint Congressional Committee on Atomic Energy as twelve to fourteen megatons. This represents an explosive force 600 to 700 times that of the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. […]

Despite the hydrogen bomb’s enormous power, Admiral Strauss said, the test was “at no time out of control.” Furthermore, he gave the nation and the world the assurance given to him by scientists that it was “impossible for any such test or series of tests to get out of control.”

William L. Laurence © 1954 The New York Times.