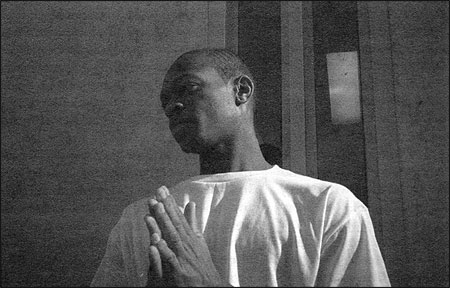

“My name is John Mills. I’m 21, a black male…in prison. I wanted to be a police officer, you know what I’m saying? When I was smaller, I used to think about that all the time. All the sirens and loud noises and blue lights. It was just something I always wanted to be. But now I hate the police. I know my life just took a big turn somewhere. I just don’t know where. My mom always predicted my life: ‘You’re going to be just like your daddy.’ He went to prison. I think he pulled like five years in prison. ‘Just like your dad.’ She’d say that all the time.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"Radio Diarists Document Their Lives"

- Joe RichmanJohn Mills is one of 1,100 young men ages 19-21 who are incarcerated at Polk Youth Facility in North Carolina. His story is part of an ongoing series called “360degrees: Perspectives on the U.S. Criminal Justice System.” This Web-based documentary attempts to put the recent growth in the prison population into historical perspective and examine the impact it has had on individuals, families and communities. Each story, and there will be eight by the end of 2002, addresses a new theme—the juvenile justice system, prison towns, children of incarcerated parents—and is told through first-person stories, data that can be examined in different ways, an interactive timeline, and online and offline discussion.

We launched 360degrees.org in January 2001 in conjunction with Joe Richman’s “Prison Diaries” series on National Public Radio. We spent several months doing interviews together. While Joe focused exclusively on John’s story for a 30-minute broadcast, we interviewed two correctional officers, the warden, and John’s mother and stepfather. We edited these interviews, along with John’s, into short audio clips for 360degrees. The site uses streaming audio and navigable 360 degree photographs to create a “sensurround” simulation of each person’s environment. While listening to each person’s story, visitors to the site can pan up, down and around the storyteller’s space—prison cells, recreation yards, living rooms, and judges’ chambers.

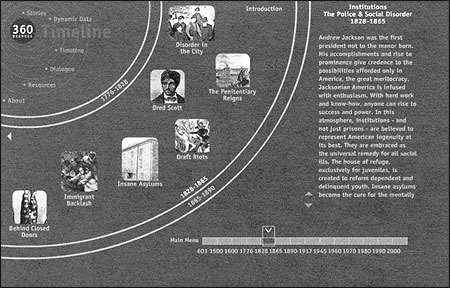

From this story section, visitors can go to an interactive timeline that shows the evolution of the criminal justice system from 601 AD to the present. Beginning with the Code of Etherlbert, which placed a monetary value on each body part, the timeline conveys the cyclical nature of the system by highlighting theories and practices that have gone in and out of fashion throughout the years. The dialogue area is a place for open discussion, e-debates between invited guests, and small closed discussion circles.

The dynamic data area is a place where we have experimented with visualizing and animating statistics, charts and graphs. This work has been conceptually difficult and the programming very intensive. Each interactive exercise requires a significant amount of data, often more than what is available, in order to generate accurate comparisons or calculate risks and odds. To develop this, we’ve worked with a number of criminolo-gists and researchers at the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Currently, the site offers two quizzes: “Are You a Criminal?” and “What’s Your Theory?” In time, we’ll offer interactive maps of neighboring communities showing the number of people going into and coming out of prison and money spent by the criminal justice system in each neighborhood, and we’ll launch three new dynamic data scenarios by the end of the year.

The idea for the project originated in 1998 when my partner, Alison Cornyn, and I read “The Real War on Crime,” a report from the National Criminal Justice Commission that detailed the ineffectiveness of tough-on-crime measures through a combination of anecdotes and statistics. It challenged us to think about how we could illustrate—using interactivity and multimedia—the rapid growth in America’s prison population since the 1980’s and its impact on our daily lives. By this time, our multimedia documentary group, Picture Projects, had already collaborated with several photojour-nalists, filmmakers and cultural institutions to create interactive documentaries including “akaKURDISTAN” with Susan Meiselas, “Farewell to Bosnia” with Gilles Peress, and “Re: Vietnam: Stories Since the War” for PBS online.

360degrees.org, as we envisioned it, was larger in scale than any of these projects. It would require a significant team of advisors, producers and programmers and, of course, a much larger budget. As with our past online projects, our goal was to capitalize on the assets of the medium: its capacity for quick computation, motion graphics, and the integration of audio and video, as well as the opportunity to cross over geographic boundaries. We wanted to reach new audiences, primarily high school and college students, that have had little exposure to the criminal justice system or to those who had come into contact with the system but wanted to know how their experiences fit into a broader picture. (We knew we were headed in the right direction when The New York Times reported that criminal justice was the fastest growing major on U.S. college campuses.) More importantly, we wanted to tell a compelling story, one that fully engages the audience through their actions on the site, and one that ultimately gets people thinking about the efficacy of our current policies and alternative approaches to crime control and incarceration.

We refer to 360degrees.org as an interactive documentary. When people hear this, they want to know how long it is. Of course, its length is determined by how the user travels through the site. The combination of high-end graphic design, storytelling, interactivity and the nature of the subject matter positions 360degrees.org somewhere between art, documentary and activism. The site has been featured at documentary film festivals, galleries and at new media trade shows. It has also been nominated for journalism awards. The blurring of the lines has made it difficult for us to get funding, yet a handful of foundations including the New York State Council on the Arts, Creative Capital, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting came on board while the project was in its nascent stages. The budget for the site resembles that of a low-budget documentary film with half of the resources going toward our production team of database programmers, Flash animators, audio editors, photography researchers, and writers. The other half goes toward the cost of outreach and marketing.

We developed the site independent of an online distributor so we’d be free to experiment with the technology, the narrative structure and, most importantly, the content. This, of course, put the task of audience building in our hands, which has been costly, but the result has been a series of enterprising partnerships and collaborations. The site averages about 5,000 hits a day and closer to 10,000 during the related NPR broadcasts. Adrienne FitzGerald, a former social worker with a degree in new media, has been working with us to bring 360degrees into high schools and universities. She created a pilot program called the Social Action Network, where students talk with ex-offenders, judges and lawyers in a guided, four-week program that takes place both online and offline. We are seeking funding to make this a national program in partnership with several educational organizations, including a criminal justice textbook publisher.

360degrees.org is in many ways an experiment in how far we can push the medium (and our resources) and how much an audience is willing to engage with a story. In this non-linear Web environment there is less narrative control. Visitors to the site will listen to characters in a different order, in different environments, and in different ways. So it is vital for us to create a “stickiness” between the stories, keeping visitors curious enough to continue exploring the site. Our goal has been to construct the overall narrative by collecting many—sometimes hundreds—of first-person stories. One of the advantages of working in this medium is the ability to change the site in response to viewer feedback. The downside is living with the feeling that the project is never complete. Built into the architecture of our sites is the space to play with different methods for storytelling.

These large-scale projects can only be accomplished through collaboration; they can be costly and incredibly time consuming. We have been encouraged by the growing community of filmmakers, writers, photographers and journalists willing to pool their experience and resources. It is a critical time, as the Web becomes increasingly commercialized, to carve out a space online for experimentation with these new forms of documentary.

Sue Johnson is a documentary photographer and cofounder of Picture Projects, a new media production company specializing in Web-based documentaries. Picture Projects’ work can be found at www.picture-projects.com.