The Beat Goes On - Its Rhythm Changes

Beats form the backbone of a newsroom, so what happens when resources shrink, new voices emerge and platforms multiply? Which topics stick around? What new beats emerge? As Twitter cranks up the demand for constant interaction, how do beat reporters handle the daily grind? How do journalists connect with news consumers in a time of information overload? As e-book reading surges, is self-publishing the way to go? Dig in to these stories—and listen to Gabrielle Goodman perform our cover’s song that she wrote.

Throughout decades as a newspaper reporter, mostly covering the civil rights movement in the South, I have been a witness to history. I covered marches, trials, speeches and midnight gatherings with protesters on their knees singing “We Shall Overcome” in whispery voices echoing in the night like a hymn in praise of freedom. I listened to the words of George Wallace, Martin Luther King, Jr., civil rights attorneys Morris Dees and Chuck Morgan, and Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley.

Despite all that came after, what I remember most vividly is an image from more than 50 years ago. One picture stays with me, haunting and informing my writing about the movement that shook our nation. Days before my 16th birthday, in 1956, I was riding home one night from my part-time job at The Tuscaloosa News with a photographer when we came upon a mob on University Avenue. Whites were protesting a young woman’s attempt to become the first black student at the University of Alabama. The angry crowd stopped a car. Men beat it with sticks. They climbed on the bumpers, jumping up and down. In the darkness I saw the face of a small black boy framed in the back window. His eyes were huge with fear. Although the mob let the car pass after a few minutes, the boy’s frightened face was seared into my memory.

A Writer’s Beginnings

I had been hired by the sports editor at the News when I was 15, after undergoing spinal surgeries and being confined to a body cast for six months. Bedridden, I fought loneliness by reading Victor Hugo, Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, and others. Instead of emptiness, my world was filled with excitement: French revolutionists, boys floating down the Mississippi, and bullfighters in Spain. I was thrilled with the magic of written words.

In a magazine, I read an article about San Miguel de Allende in Mexico called “How to Live in Paradise on $100 a Month.” At the Instituto Allende professionals taught writing. Descriptions of the Spanish colonial town put me on the narrow cobblestone streets. I pictured myself as a student there.

In my first job as a part-time sports reporter I wrote two-paragraph summaries of Friday night football games. If I wrote one word too many, my editor slashed it. If I used an unnecessary adjective, a scowl covered his face. On Saturdays I wrote headlines for sports stories going in the Sunday paper, learning the true weight of simple words.

I dreamed of writing books. Learning the art of self-discipline, I awakened early every morning and wrote for several hours. I composed a bad 150-page novel that thankfully disappeared long ago. Now and then I would unfold the article about Mexico and read it again. Finally, in the summer of 1958, after graduating from high school, I rode four trains from west Alabama to San Miguel, where I attended the writing center. In an old cantina veterans of World War II and Korea bragged about being writers, but all they did was drink and talk.

Returning to the United States, I showed my stories to professor Hudson Strode, who selected me for his illustrious creative writing class at the University of Alabama. Being admitted to his class was a prize in itself. Later I won an essay contest. The $50 check made me believe I could be successful. In the next three years I managed to sell two stories to pulp magazines. An article about Mexico sold for $100. It was enough positive reinforcement to keep me trying, a quality Strode called “stickability,” his top criteria for beginning writers.

A Witness to History

In 1965, after I was hired as a reporter for the Alabama Journal, Montgomery’s afternoon newspaper, by managing editor Ray Jenkins, who had just finished his Nieman year, I was soon assigned to cover civil rights. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was in and out of town, meeting with reporters at the integrated Albert Pick Motel. At Freedom City—several dozen tents in a Lowndes County pasture—Stokely Carmichael organized the Black Panthers. I wrote about the leaders and described demonstrations. Much of this reporting was done as a stringer for The New York Times or the Los Angeles Times or one of the weekly newsmagazines. All the while, I knew that some day when I wrote a book I would make use of this information, such as the way a courthouse built by slaves in Hayneville looked and smelled and felt and the six-by-six-by-six-foot cage where defendants were once held before trials.

After a year of reporting, I began waking early to write before going to the office. Since the days of studying in Mexico and with Strode, I yearned to write fiction. In 1966, my first novel, “The Golfer,” was bought by J.B. Lippincott. In it, my protagonist, a young white professional golfer, meets a young black who has more natural talent than he. However, both realize that in the segregated world the black man will never have the opportunity to participate in the sport. After rewriting the manuscript, following suggestions of Tay Hohoff, a marvelous teacher who had been Harper Lee’s editor on “To Kill A Mockingbird,” it was published in the fall of 1967.

I continued to study the craft of writing. In my early years I thought fiction was the ultimate. Later I determined that if a writer worked hard and delved deeply into his subjects, nonfiction was equally rewarding. The creative writing techniques I learned in Mexico and from Strode could and should be used in nonfiction.

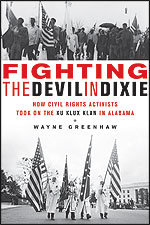

As I think back on my 22nd book, “Fighting the Devil in Dixie: How Civil Rights Activists Took on the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama,” being published in January by Lawrence Hill Books, I realize that I finally put to use the novelistic elements of the real-life drama that I was immersed in for so many years. In my new book, the action unfolds through a cast of characters including a young man who is one of only five black lawyers in Alabama in the mid-1950’s, a white lawyer in Birmingham who becomes an ardent crusader for equal rights, a white farm boy who grows up to create the Southern Poverty Law Center, an ambitious politician who spews violent racism and later becomes a born-again progressive, and a young state attorney general who prosecutes the bomber of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

Looking back on these people who are larger than life, I wonder: In fiction, who would believe them? How could you create a group of courageous Harvard graduates who came South to report what was happening in civil rights? Who would believe that these young people would stay the course after they were called names and were attacked, beaten and arrested? But they did. Like the lawyers and the politician, they kept moving ahead. As American Civil Liberties Union attorney Chuck Morgan, who had toiled in the civil rights movement for years, told a group of students at Harvard in the spring of 1973, “The people who were guarding our Southern way of life said, ‘If we give ’em an inch, they will take a mile.’ … Well, they gave us an inch, and we took a mile.” His voice and others resonate throughout the pages of “Fighting the Devil in Dixie.”

Wayne Greenhaw, a 1973 Nieman Fellow, now lives in Montgomery, Alabama, and San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

Despite all that came after, what I remember most vividly is an image from more than 50 years ago. One picture stays with me, haunting and informing my writing about the movement that shook our nation. Days before my 16th birthday, in 1956, I was riding home one night from my part-time job at The Tuscaloosa News with a photographer when we came upon a mob on University Avenue. Whites were protesting a young woman’s attempt to become the first black student at the University of Alabama. The angry crowd stopped a car. Men beat it with sticks. They climbed on the bumpers, jumping up and down. In the darkness I saw the face of a small black boy framed in the back window. His eyes were huge with fear. Although the mob let the car pass after a few minutes, the boy’s frightened face was seared into my memory.

A Writer’s Beginnings

I had been hired by the sports editor at the News when I was 15, after undergoing spinal surgeries and being confined to a body cast for six months. Bedridden, I fought loneliness by reading Victor Hugo, Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, and others. Instead of emptiness, my world was filled with excitement: French revolutionists, boys floating down the Mississippi, and bullfighters in Spain. I was thrilled with the magic of written words.

In a magazine, I read an article about San Miguel de Allende in Mexico called “How to Live in Paradise on $100 a Month.” At the Instituto Allende professionals taught writing. Descriptions of the Spanish colonial town put me on the narrow cobblestone streets. I pictured myself as a student there.

In my first job as a part-time sports reporter I wrote two-paragraph summaries of Friday night football games. If I wrote one word too many, my editor slashed it. If I used an unnecessary adjective, a scowl covered his face. On Saturdays I wrote headlines for sports stories going in the Sunday paper, learning the true weight of simple words.

I dreamed of writing books. Learning the art of self-discipline, I awakened early every morning and wrote for several hours. I composed a bad 150-page novel that thankfully disappeared long ago. Now and then I would unfold the article about Mexico and read it again. Finally, in the summer of 1958, after graduating from high school, I rode four trains from west Alabama to San Miguel, where I attended the writing center. In an old cantina veterans of World War II and Korea bragged about being writers, but all they did was drink and talk.

Returning to the United States, I showed my stories to professor Hudson Strode, who selected me for his illustrious creative writing class at the University of Alabama. Being admitted to his class was a prize in itself. Later I won an essay contest. The $50 check made me believe I could be successful. In the next three years I managed to sell two stories to pulp magazines. An article about Mexico sold for $100. It was enough positive reinforcement to keep me trying, a quality Strode called “stickability,” his top criteria for beginning writers.

A Witness to History

In 1965, after I was hired as a reporter for the Alabama Journal, Montgomery’s afternoon newspaper, by managing editor Ray Jenkins, who had just finished his Nieman year, I was soon assigned to cover civil rights. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was in and out of town, meeting with reporters at the integrated Albert Pick Motel. At Freedom City—several dozen tents in a Lowndes County pasture—Stokely Carmichael organized the Black Panthers. I wrote about the leaders and described demonstrations. Much of this reporting was done as a stringer for The New York Times or the Los Angeles Times or one of the weekly newsmagazines. All the while, I knew that some day when I wrote a book I would make use of this information, such as the way a courthouse built by slaves in Hayneville looked and smelled and felt and the six-by-six-by-six-foot cage where defendants were once held before trials.

After a year of reporting, I began waking early to write before going to the office. Since the days of studying in Mexico and with Strode, I yearned to write fiction. In 1966, my first novel, “The Golfer,” was bought by J.B. Lippincott. In it, my protagonist, a young white professional golfer, meets a young black who has more natural talent than he. However, both realize that in the segregated world the black man will never have the opportunity to participate in the sport. After rewriting the manuscript, following suggestions of Tay Hohoff, a marvelous teacher who had been Harper Lee’s editor on “To Kill A Mockingbird,” it was published in the fall of 1967.

I continued to study the craft of writing. In my early years I thought fiction was the ultimate. Later I determined that if a writer worked hard and delved deeply into his subjects, nonfiction was equally rewarding. The creative writing techniques I learned in Mexico and from Strode could and should be used in nonfiction.

As I think back on my 22nd book, “Fighting the Devil in Dixie: How Civil Rights Activists Took on the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama,” being published in January by Lawrence Hill Books, I realize that I finally put to use the novelistic elements of the real-life drama that I was immersed in for so many years. In my new book, the action unfolds through a cast of characters including a young man who is one of only five black lawyers in Alabama in the mid-1950’s, a white lawyer in Birmingham who becomes an ardent crusader for equal rights, a white farm boy who grows up to create the Southern Poverty Law Center, an ambitious politician who spews violent racism and later becomes a born-again progressive, and a young state attorney general who prosecutes the bomber of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

Looking back on these people who are larger than life, I wonder: In fiction, who would believe them? How could you create a group of courageous Harvard graduates who came South to report what was happening in civil rights? Who would believe that these young people would stay the course after they were called names and were attacked, beaten and arrested? But they did. Like the lawyers and the politician, they kept moving ahead. As American Civil Liberties Union attorney Chuck Morgan, who had toiled in the civil rights movement for years, told a group of students at Harvard in the spring of 1973, “The people who were guarding our Southern way of life said, ‘If we give ’em an inch, they will take a mile.’ … Well, they gave us an inch, and we took a mile.” His voice and others resonate throughout the pages of “Fighting the Devil in Dixie.”

Wayne Greenhaw, a 1973 Nieman Fellow, now lives in Montgomery, Alabama, and San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.