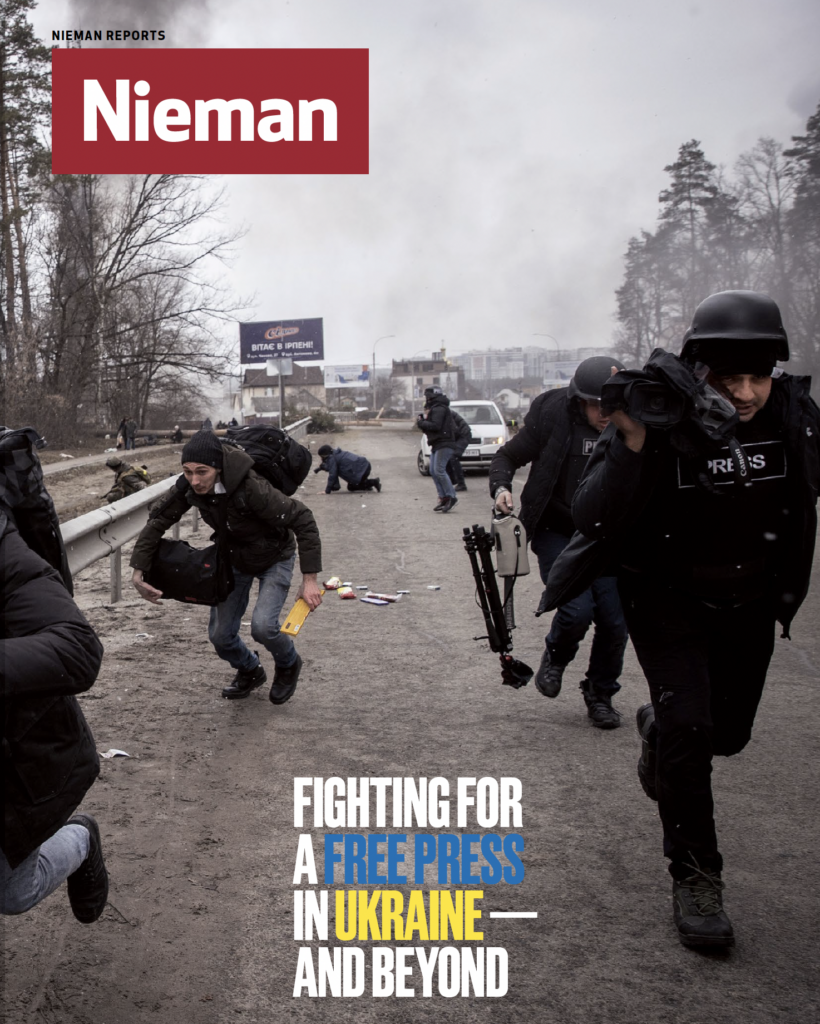

In recent years, journalism in Ukraine and other post-Soviet states has been in flux, with editorial independence reliant on foreign entities, funding in constant deficit, and press freedoms wavering. Now, as Russia’s war in Ukraine continues to drag on, the work of journalists in the country has become more urgent — and dangerous — than ever.

As civilian deaths mount, journalists, too, have lost their lives reporting on the war’s horrors. Nieman Reports takes a look at how Ukrainian journalists are reporting on the war in their home, the costs of reporting accurately on the invasion, and the growing threats to press freedom under Putin.

Dec. 20, 2016, was one of those winter mornings in New Delhi, India when everything was enveloped in the thick smog of chronic air pollution. On that day, in one of Delhi High Court’s crowded court rooms, lawyers, activists, and the press had gathered for an extraordinary case. A father had filed a civil petition on behalf of his 18-year-old daughter, Shreya, who needed a new drug for tuberculosis.

The drug, Bedaquiline, was an antibiotic manufactured in India but owned by American pharmaceutical giant Johnson and Johnson. I spent the next few months reporting this case, which she won but died in the process.

As a health journalist in India, reporting on infectious diseases like TB, HIV, dengue, and Zika was routine for me. I came of age reporting on the boom in India’s domestic pharmaceutical industry, which we routinely call the “pharmacy of the world.” Shreya’s case was a hard pivot from that. I could not reconcile that the Indian health ministry systematically denied access to medicines that were being manufactured in India.

The court case led me down a rabbit hole on tuberculosis, and I spent the next seven years tracing the evolution of the bacteria from ancient Egypt to 19th century New York before zooming the focus in on 21st century Mumbai. In writing “Phantom Plague: How Tuberculosis Shaped History,” I found that history was replete with examples of scientific progress being denied to the sick, old, poor, and vulnerable. While I was working this book, the world was brought to its knees by the coronavirus pandemic, with the fruits of modern medicine, once again, being held from developing countries. Across the world, the poor are under-treated, without compassion, while the rich are over-treated. Both scenarios are contributing to an “antibiotic apocalypse” already dawning on Black and brown nations.

“Phantom Plague” started a conversation about the role of race, gender, and caste in perpetuating plagues. As we grapple with the pandemic, we can no longer ignore the suffering wrought by a global approach to health that doesn’t care for the most vulnerable among us. Everyone deserves access to safe and humane healthcare.