The Pakistani taxi driver I have directed to the Iranian Embassy pumps his brakes as we approach the U.S. Embassy, a seven-story building that resembles the hull of a battleship. Tall and arrogant, it looms large over the Abu Dhabi Desert. I had recently started a job in the capital of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as the diplomatic affairs correspondent for a new English-language newspaper. The American Embassy is down the road from the Iranian one—close enough that the Iranians refer to it when giving directions to their own.

“Here?” the driver asks, turning around for another quick look. I have olive skin and my dark hair is dutifully covered for the occasion. But the accent behind the hijab is unmistakably American. “No, the Iranian Embassy,” I repeat, this time with more emphasis.

As he pulls away from the curb, I feel a deep pang of separation, coupled with excitement: This is the closest I’ve been to Iran in more than 20 years. The embassy’s turquoise-tiled walls, evoking something in my childhood, shimmer in the distance. What look like thick black scribbles give way to fancy calligraphy—Qur’anic verses, I assume—as we get closer.

Like many Iranian Americans, I feel as if I’m from a broken home: The parents are divorced but still feuding after three decades. As a journalist, my position is more precarious.

In what has been called a cold war between Iran and the United States, the UAE has emerged as a Vienna of sorts—a place where America’s Iran-watchers can mingle with thousands of Iranians. One hub for this is the expanded Iran Desk at the U.S. consulate in Dubai, the more cosmopolitan UAE city-state up the coast from the capital. If Iranians are suspicious of journalists, it’s partly because our reporting jobs can seem like the perfect cover to gather intelligence.

Iranians have a deep-seated paranoia about spies and conspiracies. There is a long history of political intrigue to explain such suspicions. In 1953, a CIA-engineered coup ousted the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh and reinstalled the shah, under whose reign American agents roamed the land. CIA and Israel’s Mossad reportedly trained Iran’s secret police. More intriguingly, CIA director Richard Helms was appointed U.S. Ambassador to Iran after he left the agency in 1973. (Incidentally, Helms started his career as a journalist.) When militants seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in 1979, they dubbed it “the den of spies.”

The 1980’s were particularly bleak. Soon after the Islamic Republic was established, the regime consolidated power in the brutal ways a state does. While it fought an eight-year war that its neighbor Iraq started, it also waged internal battles with domestic foes—the Kurds, the communist Tudeh Party, and especially the Iranian Mojahedin, a quasi-Marxist cult on the U.S. terrorist list.

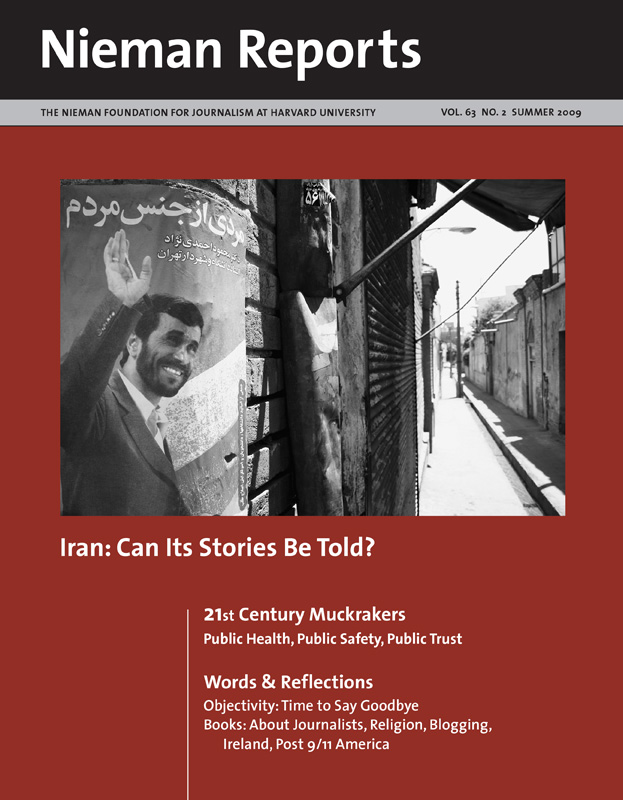

Much has changed in Iran since that decade in which I left Iran, but some important progress made in the 1990’s has been stymied by those who think the way forward is to revert to practices they themselves deplored under the shah—and ones that led to a revolution. Economic and cultural reforms slowly put in place after the war were effectively rolled back in this decade, especially since Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took office in 2005. Things got worse the following year, when the Bush administration asked Congress for tens of millions of dollars to secretly fund NGOs and activists to destabilize the Iranian government. It stoked government paranoia and became an effective tool in the hands of officials who have used it to stifle dissent and spread fear.

If the Iranians believe this is vital to their survival, the fear may be misplaced. As Ervand Abrahamian, a U.S.-based Iran scholar, argues in a recent paper, it was not a reign of terror, the eight-year war, oil revenue, or even the strength of Shi’ism that sustained the Iranian regime—but populism. The challenge the regime now faces, according to Abrahamian, is to “juggle the competing demands of these populist programs with those of the educated middle class—especially the ever-expanding army of university graduates produced, ironically, by one of the revolution’s main achievements. This new stratum needs not only jobs and a decent standard of living but also greater social mobility and access to the outside world—with all its dangers, especially to well-protected home industries—and, concomitantly, the creation of a viable civil society.”

The Iranian Press

The press is one place to start. The media in Iran is often state owned and always closely supervised. Those newspapers not run directly by the state are associated with political parties and prominent figures whose factional rivalries sometimes spill over into the papers. Those in power often assert it by shutting down a rival’s mouthpiece.

There’s another reason to reform the press in Iran. Since a systematic crackdown, which has included journalists, bloggers, academics and researchers, journalism there has become synonymous with jail and tyranny. Adopting more liberal press practices is likely to do Iran far more good than harm, and here’s four reasons why:

- The work of any journalist or propagandist pale in comparison to the far-fetched scenarios swirling in Iranian living rooms, taxi cabs—and, above all, in the Iranian imagination. I’ve heard them all and, believe me, reality is not always stranger than fiction.

- Satellite dishes are illegal but on the ascent in Iran. They crop up faster than officials can take them down. Most of the programs they watch stream in from Los Angeles, where there is a lot of singing and dancing, but from where dissidents have been unsuccessfully trying to topple the regime for 30 years. Both the British-funded BBC Persian service and the U.S. government-backed Voice of America have expanded their radio broadcasts to include television. So great is the audience, that essentially the government is not shielding anyone from anything.

- Foreign journalists have a difficult time obtaining permission to report from Iran or to set up bureaus there. Visiting reporters are obliged to employ “minders” from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, something they fail to tell their viewers and readers. This might help authorities feel in greater control of the information that trickles out. But the news vacuum about Iran is filled not by The New York Times or ABC News but by information disseminated by interest groups, dissidents and other much more biased parties.

- What do the arrests and jailing of journalists and bloggers accomplish? If anything, it attracts more attention to their work. And it reinforces the worst stereotypes everyone already has about Iran. Why not break them?

Tehran Bureau: An Online News Hub

The decision to create TehranBureau.com, an online news magazine to which journalists familiar with Iran contribute stories, emerged out of many conversations and e-mails with a classmate from Columbia Journalism School. Each of us wanted to report news about Iran, but not in the simplistic way that country is too often covered by the Western mainstream media. As much to avoid the dangers of Iran’s factional politics as to escape the Western news media’s bias against Iran and Iranians, we decided to take advantage of the Internet and set up a virtual bureau. In part, our thinking was guided by us knowing that Iranians are as much plugged in as any developed society.

At a time when world news should be more important than ever, news organizations continue their contraction, and to do this they’ve shuttered or scaled back foreign bureaus. Though the trend in journalism is specialization, news organizations appear to be investing fewer resources in the cultivation of editorial and reporting staffs who can become, in effect, area experts.

This reduction in reporting knowledge and resources has consequences, as information slips through as news that shapes Western perceptions and policy. Four years ago, soon after the last presidential election—the one Ahmadinejad won—a black-and-white photograph purporting to show the new president as a hostage-taker in the 1979 embassy takeover circulated widely in the media. To an Iranian, certainly, the person in the picture looks nothing like him. I e-mailed a professor who was working on a book about the hostage crisis to get his perspective.

“That was first sent out by an MEK-affiliated Web site,” he wrote back, referring to the Iranian Mojahedin, an Iranian opposition group living in exile. “The two individuals in the photo have long since been identified as a MEK partisan who was later executed and another student who was killed in the Iraq War.” More interestingly, in the eight years Ahmadinejad’s predecessor was president, the media remained quiet or ignorant about the leading role of many reformists close to President Mohammad Khatami in the embassy seizure, including his brother.

One of my primary motivations in setting up Tehran Bureau in 2008 was to assemble a staff in which reporters and editors speak the language—and can tell people apart. Speaking Farsi helps expand our ability to gather news. It means we can tap into a more extensive network and speak to more Iranians, even if we’re not based in Tehran. We can read Iranian bloggers—those who write in Iran and those who live in exile—and scan the Iranian press and, by reading between the lines, we can ultimately deliver a more reliable product, even if we do so with barely any financial support. (We refuse to take money from any government agency, religious or interest group.)

Here are two examples of coverage of Iran by Tehran Bureau:

- In March, Gareth Smyth, who reported from Iran for the Financial Times, wrote “Hot times and cool heads,”1 about political dynamics inside of Iran and the United States that might result in the two countries engaging in dialogue.

- The impact of Mohammad Khatami’s withdrawal as a presidential candidate has been written about from several angles in blog posts as part of Tehran Bureau’s reporting on the Iranian election in June.

Surprises Along the Way

The Iranian ambassador I had a meeting with that day had been the foreign ministry spokesman for a long time. He was sophisticated and media savvy. At that time, the circumstances in the UAE were stacked against me. The paper I was writing for had no name and was still months away from being published. As we started dry runs, I wrote stories on deadline for a paper with no name that no one outside the newsroom saw. Plus, as an Iranian American, I knew the Iranian authorities would never trust me. But in the course of my work, they gave me the benefit of the doubt and access and treated me with respect and my American colleagues, even more so.

My experience wasn’t limited to the foreign ministry. The first time I spoke to one of Tehran’s hard liners, I was based in London and working as an associate producer for “Frontline.” After many months had passed and it was pretty apparent my colleagues’ visas weren’t going to come through, I picked up the phone and dialed a number that wasn’t all that difficult to find. “Salaam,” I said, introducing myself. “I’m calling from London,” I said. Strike one. (Many Iranians believe the British are worse than Americans when it comes to plotting against Iranians. The 1953 coup was initially hatched by the British, after all.) I continued, “I work for an American television station.” Strike two. “We’re making a documentary about U.S.-Iran relations since 9/11,” I, an Iranian American, said. Strike three. I took a deep breath and braced for the worst.

“Can I see your programs on satellite television?” this official with a provincial accent asked after a pause.

“No,” I replied, but I sent him a link to “Frontline’s” online archives. And I was impressed by his gmail address.

After a couple of days, he called me. “It’s a good program,” he said. “It’s certainly better than the other television programs there, anyway.”

Not long after this conversation, we were in.

Kelly Golnoush Niknejad founded Tehran Bureau in November 2008, initially as a blog. She serves as managing editor as well as one of its reporters. Tehran Bureau can be found at www.tehranbureau.com. Information about the “Frontline” documentary, “Showdown With Iran,” is at www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/showdown/.