Cameras, Action and Accountability

"The Web is more important in this presidential campaign and the Pennsylvania primary than the newspaper. Think Web first, and then think newspaper, because you're going to do something different for the newspaper. I'm not saying the newspaper's not important, but first think Web, because if you don't think Web first, it's going to be too late to think Web."

Absorbing this political season's English- and Spanish-language coverage can leave a person with a severe case of whiplash. It's like trying to follow two completely different elections.

When I started working for the ethnic media news site New America Media in San Francisco six years ago, I didn't fully understand how "ethnic" and "mainstream" media differed. What I have discovered since has taught me that the language is perhaps the least of what separates them.

At New America Media, journalists translate and report on news that appears in ethnic media in communities across the country. As an editor and Latino media monitor, I've tracked stark differences in the ways the Latino press cover political issues when compared with the English-language press. These differences become clearer when we compare the coverage of and commentary about the presidential campaign. And these differences get magnified when one analyzes coverage about the "Latino voter" in the context of racial voting patterns.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

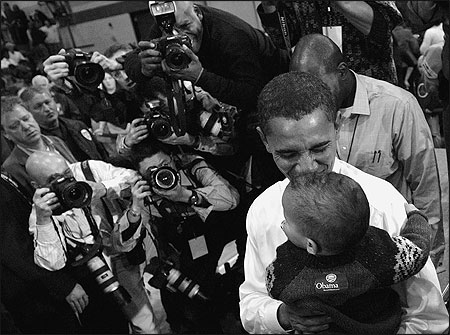

Univision and ImpreMedia partnered in a national citizenship drive and a get-out-the-vote campaign.During this primary season, the presidential candidates paid more attention to Latino media than ever before. For example, some of the Democratic and Republican candidates appeared for the first time in Spanish-language forums on Univision. And it is certainly the case that Spanish-language media have played an important role in driving people to the polls — thereby exemplifying the words heard at pro-immigration marches: "Hoy marchamos, mañana votamos." [See author's note.] ("Today we march, tomorrow we vote.") These trends have not been accompanied, however, by a corresponding shift in thinking by most Americans. What seems apparent to Latinos is that most people in the United States still think of their country as being a black and white society. And as the topic of race dominated much of the English-language press's political coverage, many articles dealt with questions about whether Latinos would vote for a black candidate. Racially tinged spars between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama made the front pages of major English-language newspapers, but such stories were rarely found — and certainly not featured — in the Latino press.

For a while, at least, the Spanish-language press ignored this racial issue entirely. For some, this decision might have been based on the volatility of this issue — and a desire not to further inflame tensions between blacks and Latinos. For others, there might have been a sense in Latino newsrooms that the race issue was being hyped by the English-language media and simply didn't merit such coverage. Whatever the reasons, the absence of this story in the Latino press seemed to be clearly a conscious editorial decision.

Instead, the Spanish-language press focused on the issues deemed important by members of Latino communities — the economy, the war in Iraq, immigration reform, health care, and education. While the English-language news media tended to focus on horserace aspects of the race, the Latino news media devoted much more of its coverage to what the candidates were saying about these key issues.

Even so, there came a time when the Spanish-language press had to turn its focus to the topic of race because of the sheer volume of commentary and articles circulating about how it might affect the Latino vote in the Democratic primaries. Three weeks before the February 5th Super Tuesday, an editorial in New York City's Spanish-language El Diario/La Prensa observed that speculation about how Latinos would vote was being framed in the English-language news media around a "false dichotomy" of race vs. gender.

In essence, mainstream news reports were attempting to explain Latinos' support for Clinton in the context of an old paradigm of black-white politics — with the assumed result being that antiblack racism would be to blame in the anticipated vote against Obama.

The factors that compel Latinos to vote as they do are far more complex. At the same time that public opinion polls were finding that Latinos overwhelmingly favored Clinton, La Opinión, the largest Spanish-language newspaper in the country, endorsed Obama. This was the first time this newspaper had endorsed a candidate in the primary.

La Opinión called Obama a more visionary candidate, noting that he supported issuing driver licenses for the undocumented, was committed to proposing immigration legislation during his first year in office, and cosponsored the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act. When Clinton won the California primary, La Opinión and other Spanish-speaking media credited her campaign's long history of reaching out to Latinos. "Someone will surely attribute an African-American candidate's limited support among Latinos to racism," noted an editorial in La Opinión. "This is simply not the case. While there are prejudices in all communities, the reasons for Obama's loss were his failure to effectively reach out to Hispanics, Clinton's name recognition, and an excellent candidate backed by a well-run organization."

Many opinion pieces in the Latino press were quick to point to some generalizations making their way across pages of English-language newspapers and worked to debunk them. Most notable was the story line in which Latino voters were described in ways that made them seem monolithic. Raoul Lowery Contreras, writing in a California-based online weekly, HispanicVista, observed that an editorial in the Los Angeles Times, for example, provided no ethnic or philosophical distinction between Hispanics living in Virginia and those residing in Chicago or the Southwest or Texas.

In his column, "Mexican Tastes Do Not Include Obama," Lowery made the case that Mexican Americans in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas simply didn't buy into Obama's leftist message of hope. Yet Obama did well with Virginia Salvadorans, who came to the United States to escape their civil war. "They carry with them leftist souls that have no embodiment in American politics other than in Obama, the most liberal senator in the Senate," Lowery wrote.

Other commentators joined in the attempt to dispel what they believed to be myths about the Latino electorate. They noted, for instance, the times when Latino voters have voted for black politicians — from the days of Vicente Guerrero, the mulatto Mexican president who outlawed slavery in 1829, until recently in mayoral elections in several U.S. cities. In fact, they pointed out, even the terms "Latino vote" and "black vote" are misnomers since many "Latinos," including Puerto Ricans, Dominicans and Cubans, have African ancestry.

As some in the Latino press scrutinized how the English-language media were addressing these core issues of race and identity, a lively debate took place in Spanish-language newspapers about whether Obama could speak effectively to the concerns of Latino voters. When Obama addressed the controversy over Reverend Jeremiah Wright's sermons and called for a national dialogue on race, Spanish-language news outlets were divided; some called Obama a "symbol of unity;" for others, what he said was seen as a "sign of divisiveness."

Miami's El Nuevo Herald columnist Adolfo Rivero Caro compared Obama to former Cuban President Fidel Castro and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez. "Seducing the public, talking of the extraordinary future that awaits them, always has seemed to me a cheap trick," he wrote. Writing for the same paper, Vicente Echerri noted that Obama's "racial origin, ideal for representing the American who has transcended prejudices and stereotypes, will serve him very little when he identifies so absolutely with a racial group, with a black church presided by a prophet of racism." Meanwhile, an editorial in La Opinión the day after Obama's speech praised it as a symbol of unity, saying "the social and economic challenges faced by whites, blacks, Latinos and immigrants are similar whatever our obvious differences."

At the heart of their arguments, all of the Latino commentators seemed to agree on one thing: The usual black-white dialogue about race is long overdue for an overhaul.

Elena Shore is an editor with New America Media in San Francisco, California.