Late in 2003, Habibia High School in Kabul was one of Afghanistan’s better secondary learning institutions. Built largely with funding by the United States many years earlier, Habibia nonetheless offered a snapshot of the difficult road that stretched behind and ahead of the Afghan people.

The school, like so many buildings in the country’s capital, had been bombarded and pillaged during the civil war that embroiled Afghanistan after the Soviet withdrawal in 1989. Some of those who were responsible for this destructiveness would become allies of American troops after September 11, 2001, but this earlier internal struggle for power made Afghans yearn for calm and order, no matter how harshly and brutally it was bestowed. For a time, ironically, the Taliban fulfilled that yearning.

Jagged lines in the walls of the hallways and classrooms revealed where electrical wires had been ripped away. Teachers wrote lessons on pockmarked, bullet-riddled blackboards. Students hung blankets over doorways without doors, trying unsuccessfully to keep out the cold. They had to traverse a drab and dusty field to use a makeshift bathroom about 200 yards behind the school.

On a brief tour of the school, photographer Benjamin Krain and I were told we could not learn names or quote anyone. The Ministry of Education set these ground rules, with Ben acting as our negotiator; either we complied or, it was made clear to us, we would not be let inside. Working within the constraints, Ben photographed the extraordinarily difficult conditions under which learning was taking place in this Kabul school. His images belied the usual story line told about how Afghanistan was returning to a sense of normalcy, with education leading the way.

By the time we made this school visit, I wanted as little to do with most Afghan government officials as possible. I had realized that bargaining usually resulted only in hours and hours of wasted time, sometimes days. At the start of our month-long reporting journey, it was not unusual for us to arrive an hour ahead of schedule for an interview, wait two, even three hours to be granted an audience with an official, and then have our time with this person abruptly end after 15 or 20 minutes. Because interviews required an interpreter, five to 10 minutes of linguistic confusion inevitably occurred, leaving us often feeling frustrated and exhausted by what little had been accomplished.

At Habibia, a so-called minder stayed with us as we walked around the school. “You can’t use my name,” this man said, as we lunged up staircases where stairs were missing and rebar showed through jagged, crumbling concrete, “but things are not good here.” On our way out of the school, we ran into a group of students. One boy said students wanted to study and learn “but those rooms are so cold, our fingers freeze.” Just then the headmaster, wearing a white prayer cap and a salwar kameez, a traditional full-length shirt and trousers, came outside and watched and listened. This boy noticed him but kept on talking as his buddies gathered around him in an encouraging way. “A couple of your senators were here a few months ago,” the boy was telling us, but by then Ben and I were being encouraged to get into our vehicle and leave. “They said they would help us.”

Afghan Coverage Fades Away

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette Executive Editor Griffin Smith and Managing Editor David Bailey asked Ben and me to go to Afghanistan in early September 2003. By then the Iraq War was about six months old, and the building Iraqi insurgency was crowding stories from Afghanistan off the front pages — not to mention the inside pages — of newspapers. With some notable exceptions, most news service stories regarding Afghanistan seemed not to delve into what was actually happening in the wake of the promises made by many nations to help the country rebuild.

While the Democrat-Gazette has a record of sending teams to distant places — most recently to Iraq — Smith and Bailey’s request came unexpectedly. Neither had an agenda, other than wanting us to examine how the purported reconstruction effort was going. They and the paper’s publisher, Walter E. Hussman, Jr. encouraged us to examine the pace of the purported reconstruction, believing that as our state’s “paper of record” not to do so would be a disservice to our readers. The cost of our trip paled against that objective, for the sad fact was that journalistic interest in such coverage was dissipating. Afghanistan was already being called “the forgotten war,” even though it was costing U.S. taxpayers about one billion dollars a month to pay for military, security, humanitarian and reconstruction efforts.

With these rebuilding efforts only in their second year — and after two decades of war that had devastated this dysfunctional country’s infrastructure — it would have been naive of us to expect to see evidence of enormous progress. Still, most of the stories coming out of Afghanistan never seemed to define clearly what reconstruction meant to the Afghan people. Instead, we found plenty of stories regurgitating how U.S. and Afghan officials were aligning their efforts in a few key areas and using those to define “progress.”

Typical stories told of Afghans listening to music or flying kites again, activities banned under the Taliban as being contrary to religious devotion. Other stories spoke admiringly of a perceived Kabul renaissance, with car dealerships opening, new restaurants springing up, and theaters playing Bollywood (Indian) movies. Soon after Ben and I returned home, I watched a cable television reporter in Kabul, standing in front of a building under construction, describe in glowing terms how U.S. efforts were responsible for progress in Afghanistan; he used this building to make his point. The reporter failed to mention — and I can’t be sure whether he’d asked questions to find out — that this building had been under construction for about a decade.

Meanwhile, the United States and the United Nations were erecting multimillion-dollar complexes for their employees, who like many Afghan officials drove around in expensive sports utility vehicles. At the same time, Care International and the Center on International Cooperation reported that only about one percent of Afghanistan’s needs had been met. So for the typical Afghan, who lives on about one dollar a day, the “reconstruction” developments that were being reported meant nothing.

In going to Afghanistan — and taking a look at the reconstruction dollars and what they had accomplished for the Afghan people — I hoped our coverage would take readers far beyond the customary themes and anecdotes.

Arriving in Kabul

After a month of preparation — arranging interpreters and drivers and working with a travel agent to find a way into the country — we landed at Kabul’s international airport on October 16th. We had a month to do our jobs, but we encountered a problem immediately. The interpreter and driver we expected no longer were available. Fortunately, we had a back-up interpreter and a driver who came with him. But this interpreter had commitments and would be available to us only a few days each week. This early disappointment foreshadowed much about our time in this country — a lesson about how challenging reporting from such a place can be. During our first two weeks, we filled in gaps by hiring this interpreter’s friend, but he had little experience and came without other references. We could hire him or remain idle three days each week. We hired him. (After two weeks, we were able to fill in the gaps with a more experienced interpreter.)

Finding the right interpreter is essential. This person not only facilitates conversation but also sets up interviews, provides valuable information on cultural sensibilities, and offers blunt advice on what places are safe for Westerners. Given these skills — and necessity — they earn considerably more than most Afghans; the rate at the time we were there was between $50 and $75 a day for the interpreter, with another $50 for the driver. The cost depended on the day’s destination and didn’t include meals.

Coming to Afghanistan for the first time from the United States requires time to make both the physical and mental adjustment. Getting vaccinated against disease and infection is necessary, but it’s virtually impossible to avoid illness. Contact with an infectious source left both Ben and me feverish for a day or two. Reading the country’s thousands of years of history helps but, once on the ground, the distant past recedes as the present must be confronted.

Finding Stories to Tell

“The Americans do not consider Afghans as human beings on this globe,” Akhtar Mohammad, a 37-year-old man, said to me in anger as Ben and I walked through a neighborhood in Kabul that was mistakenly bombed soon after the U.S. military strike against al-Qaeda and the Taliban began. We’d asked our lead interpreter, Najib, to bring us to this neighborhood called Khana, meaning “cement house,” after he told us about a family killed in the early bombings. As we stood before the rebuilt adobe-like house, its new residents didn’t want to talk. But anger about what happened here visibly percolated in Mohammad, a man who walked by. A boy who was on the roof at the time of the bombing had his body cut in half, Mohammad told us. As he spoke, a crowd of neighbors gathered, still seething over the assault that they said killed a family of five, six, and maybe eight.

“When the 11th of September incident happened,” Mohammad said, “most Muslims became worried about it, and in the [United] States people expressed their sympathy for [the victims]. But here, what happened here, you know … there were innocent people here, and the Americans bombed them…. But nobody even showed up to say, ‘We are sorry about this.'”

Dealing with this kind of understandable animosity was a constant struggle, whether we were in Kabul, Ghazni, Mazar-i-Sharif or other places in the country. Some people, it seemed obvious, just hated the sight of us. Najib explained their hatred one night as we were driving back to Kabul after a day spent in the Panjshir Valley. While we avoided the thieves and thugs along Old Bagram Road, he explained that after bombs started to fall, hundreds of people gathered near Kabul University to listen to a well-respected Afghan intellectual question the motive.

“Listen to me,” he told them. “The Americans are very good people. They are nice. You know why — especially compared to the Russians — because the Russians were only throwing bombs on Afghans, nothing else, only bombs. But the Americans — they throw bombs with biscuits.” He was referring to the MREs (meals ready to eat) that U.S. warplanes dropped throughout the country, even as other planes dropped bombs. Most Afghans didn’t know how to eat the meals, we were told, so they did them no good, though some did come up with ways to sell them. On Chicken Street, one of Kabul’s notorious commercial districts, MREs were being bought and sold two years later.

Following the billions of dollars in aid that has been promised to Afghanistan — much of it in the years since Ben and I were there — remains a crucial story to tell, yet one that I rarely see getting the attention it deserves. In January of this year, President Bush asked for an additional $10.6 billion, an amount just about equal to what the rest of the world pledged a year before, with most of it intended for military and security needs. Not forthrightly addressed in the pledges — or in reporting about them — is the fact that they aren’t necessarily binding. Delays in getting the money to Afghanistan also have chipped away at Afghans’ trust. Of the roughly $8.5 billion to $9.6 billion that the world community promised Afghanistan by late 2003, for instance, only about a third of it had actually reached the country, and little of it went to reconstruction efforts, which had been its perceived intent.

RELATED WEB LINK

View Democrat-Gazette’s Afghanistan Section »

– ardemgaz.comIn the Democrat-Gazette’s 16-page special section with our words and color images from Afghanistan, we attempted to examine the reconstruction efforts, telling readers about the successes and failures we’d observed. This topic was explored in the context of Afghanistan’s enormous raft of problems, including sanitation challenges, the removal of land mines, and the millions of refugees who had returned home, mostly from exile in Iran and Pakistan.

Kabul University, considered by some to be the Afghan equivalent of Harvard University, mirrored the lack of progress around the country. As Ben and I did our reporting there, we were told that some areas had not been fully cleared of unexploded ordnance. And surrounding Soviet-style, cookie-cutter dormitories were carcasses of bombed out buildings that functioned as the students’ toilets. They had become dumping grounds of human waste. Using them, as I had to one day, was an exercise in agility and hope, the piles of droppings virtually indistinguishable from the ground itself.

Kabul didn’t have much of a waste management program, with the United Nations estimating that the city generated about 900 tons of garbage each day, yet only about 290 tons were being collected. The remainder stayed in streets, alleyways, and outside the dorms at the university. At one point we found ourselves behind a large dorm amidst giant piles of garbage. And there were mounds of maggots. The stench lingered with me for days.

Actually, it’s hard to avoid stench in Afghanistan, especially in one of Kabul’s refugee camps, where people like 25-year-old Fahima struggled to survive. One day she sat in her small hut, in despair, and told us how she’d just sold her 10-day-old daughter, Nagina, for $200 to a stranger she met on the streets so she could buy food. Recently her husband was killed by a land mine and, with four other children to care for, she was destitute.

“What kind of mother sells her child?” she asked, trying to hide her shame by covering her face with a scarf. Later, she tried to shift the blame to another woman, who came into the hut and denied responsibility. All she did, the woman said, was stop Fahima from selling one of her boys.

“I said, ‘If you want to give someone, give the daughter. The boy will work for you,'” the woman said in her defense.

A quarrel between the two women ensued; the children started crying. After a while, Fahima simply stopped and said what to me summed up our experience reporting in Afghanistan: “What I told you is true, and what she told you is true.”

The statement sounded uncannily like those of U.S. and Afghan officials when we questioned them about the undeniable dearth of reconstruction. They said progress had been made. Then they admitted that it hadn’t amounted to much.

Bob Wigginton is an assistant city editor at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Strife, revolution and invasion have ravaged Afghanistan and its people for centuries. Now a fledgling democracy holds the promise of progress and peace. But leadership outside the capital is fractured and fragile, and forces of the Taliban are regrouping in border provinces. Poverty, drought, famine and disease plague the country and impede progress. Massive challenges lie ahead, but Afghans are cautiously rebuilding their society, hoping to avoid a return to the power struggles of the past.

An instructor at Habibia High School in Kabul, Afghanistan writes an assignment on a bullet-riddled blackboard. The school, built largely with funding by the United States many years earlier, came under heavy bombardment during the civil-war fighting in the 1990’s. Now more than 15,000 students attend classes there despite the damage to the building, which does not have electricity or running water. Photos by Benjamin Krain/Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

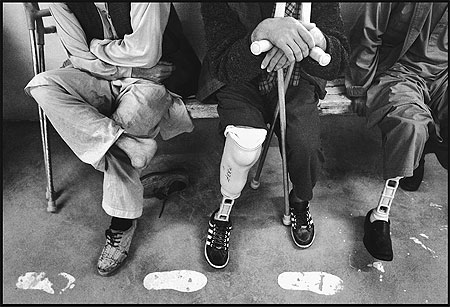

Land mine victims are fitted for prosthetics at the Red Cross Orthopedic Center in Mazar-i-Sharif. Afghanistan is one of the most heavily mined countries in the world, killing or injuring at least 150 people each month. The existence of land mines as an unexploded ordnance has complicated reconstruction efforts.

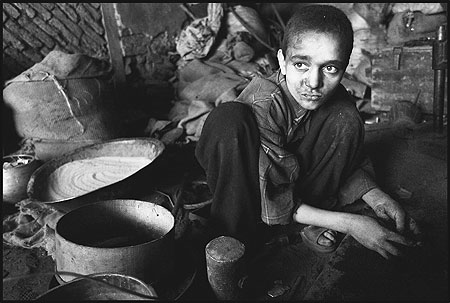

A young boy works unpaid in a blacksmith shop in Kabul. The shopkeeper claims the boy is gaining valuable experience as an apprentice. Thousands of children toil in shops and factories throughout Afghanistan, earning little or no money.

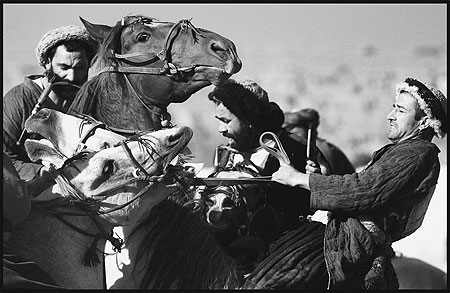

Horse riders compete in a buzkashi game at the Military Sports Club in Kabul. Typically played in northern Afghanistan, the game is a remnant of an old Mongol event in which horsemen try to get control of the headless goat carcass and move it to the scoring area. To many Afghans, buzkashi is not just a game, it is a way of life. Teamwork and communication are essential.

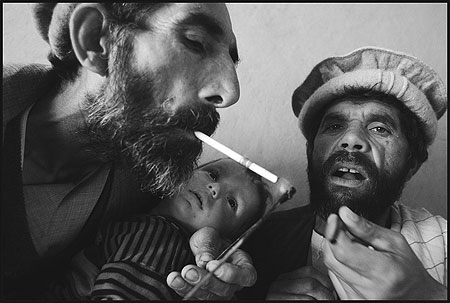

Drug addicts smoke pure opium paste while one holds a baby in Kapisa Province, about 100 miles north of Kabul, where many farmers are growing opium-producing poppy plants. Afghanistan is the world’s leading producer of poppy, which fuels the heroin drug market. Farmers are claiming they have no option other than to grow this money-producing crop.

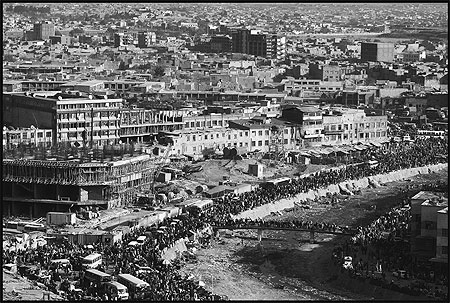

Hordes of people crowd the bazaars along the Kabul River. After years of drought, the river is now full of refuse and human waste, causing major health problems for many residents who wash food and clothes in the water.

A bombed-out bus window frames the war-ravaged Darul Aman Presidential Palace in Kabul. More than half of this capital city is rubble from 25 years of power struggles.

.jpg)