While I was writing this, I read that another newspaper closed in Iowa. It’s likely you never heard of it, but the La Porte City Progress Review was 127 years old.

You might have heard of The Storm Lake Times, another small Iowa newspaper. Its editor, Art Cullen, won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing.

But national renown doesn’t shield Cullen from the same circumstances. The crisis of the pandemic on top of a shaky economy for newspapers has been debilitating.

“If something doesn’t change in the next year or two, we will be closed,” Cullen said.

The newspaper industry has been suffering for the past two decades. Research from the University of North Carolina found that in the 15 years leading up to 2020, “more than one-fourth of country’s newspapers disappeared” and “half of newspaper readers and journalists have also vanished.”

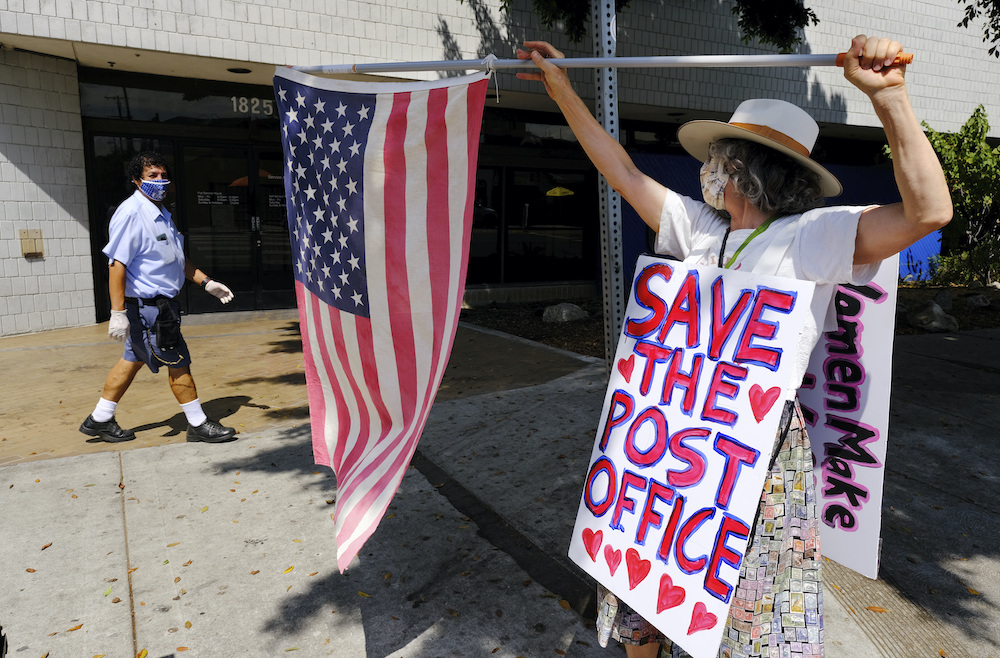

An institution that could immediately aid the survival of hundreds of small newspapers is the same one that helped us vote during a pandemic: the post office.

Unless you live in a small town, you might not have noticed that most small community newspapers are distributed by the U.S. Postal Service. (So are some large-city newspapers, for rural customers.)

The mail is not a new mode of newspaper distribution. The Postal Act of 1792, one of the earliest pieces of U.S. congressional legislation, helped to make newspapers a flourishing part of life in the United States. The act settled two debates about newspapers and the mail.

First, it ensured that every newspaper would be admitted into the mail system, so the government would not be the arbiter of which newspapers were distributed by mail.

Second, there was a vigorous argument over whether newspapers should be carried for free, or pay a reduced rate. Southerners worried that the larger Northern newspapers (many of them anti-slavery) would overwhelm the South if they were distributed for free, so the “reduced” postal rate prevailed.

Since then, newspapers have been distributed through the mail at reduced rates as a public service, a covenant that was again made explicit in the Postal Policy Act of 1958. In 1960, second-class postage charges covered only 23% of the cost of mailing.

But the covenant began to unravel after the reorganization of the postal service in 1970. Rates increased, and by the 1980s, second-class charges covered more than 100% of the postal service’s costs of mailing. In other words, the USPS was making a profit on delivering periodicals. In the 2000s, periodical rates dipped below 100% of costs again, but the premise that periodicals bear the full USPS handling costs and overhead still remains.

We are now at a critical moment for the nation’s newspapers. A useful policy proposal for today is to recover a great idea from 1792 – that newspapers should be freely distributed by the U.S. Postal Service.

Yes, eventually, digital distribution will be the norm, but it may be many years away for most newspapers. As news industry analyst Ken Doctor has noted, pushing newspapers to digital too soon would be like “burning a bridge they still need to cross.”

Large national papers like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal are finding sustainable models with digital subscriptions. For large regional and metro papers, “digital-only delivery may offer a lifeline,” says Penelope Muse Abernathy, the University of Northern Carolina researcher, but only if they can convert tens of thousands of print subscribers. That represents a dramatic drop in revenue for many publishers, when the digital subscription price point averages 23% of the print subscription price. For the nation’s thousands of dailies and weeklies, with small market sizes and only a few thousand subscribers overall, Abernathy argues that digital subscriptions and advertising generate relatively insignificant revenue.

Fully subsidizing print distribution covers a substantial fixed expense and can help sustain most of the nation’s 6,730 newspapers for what may be a very long transition period.

But, this must be done with more support for the USPS, which is also at a critical moment in its history. The USPS is chronically underfunded, and its collapse would threaten free elections and a major distribution system for newspapers. Sufficient financing for the post office and full support for newspaper distribution by mail would benefit two of the nation’s most fundamental civic institutions.

What difference would free mail distribution make for small-town newspapers, where postage is the third largest expense, after payroll and newsprint?

Matt Bryant, publisher of the Southeast Iowa Union, said “it would definitely help” and that postage makes up about 4% of his total expenses.

At the Iowa Falls Times-Citizen, Tony Baranowski, director of local media, said “no postage would definitely be a relief for us … It would change the shape of our budget.”

And, at The Storm Lake Times, “It would be a huge help to us,” Cullen said.

How much would it cost to completely subsidize newspapers distributed through the mail? In fiscal year 2020, the USPS generated $73.2 billion in revenue, although it still is awash in red ink from annual shortfalls and billions in unfunded liabilities. Revenue from newspapers and magazines combined in FY2020 was $1 billion; covering that cost would amount to about 0.02% of the federal budget.

There is no single answer to save newspapers, but we cannot afford to lose more of them. Fully subsidizing second-class mail delivery of newspapers is a public service that our democracy desperately needs now.

Christopher R. Martin is a professor of digital journalism at the University of Northern Iowa and a Center for Journalism and Liberty Contributing Scholar.

You might have heard of The Storm Lake Times, another small Iowa newspaper. Its editor, Art Cullen, won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing.

But national renown doesn’t shield Cullen from the same circumstances. The crisis of the pandemic on top of a shaky economy for newspapers has been debilitating.

“If something doesn’t change in the next year or two, we will be closed,” Cullen said.

The newspaper industry has been suffering for the past two decades. Research from the University of North Carolina found that in the 15 years leading up to 2020, “more than one-fourth of country’s newspapers disappeared” and “half of newspaper readers and journalists have also vanished.”

An institution that could immediately aid the survival of hundreds of small newspapers is the same one that helped us vote during a pandemic: the post office.

Unless you live in a small town, you might not have noticed that most small community newspapers are distributed by the U.S. Postal Service. (So are some large-city newspapers, for rural customers.)

The mail is not a new mode of newspaper distribution. The Postal Act of 1792, one of the earliest pieces of U.S. congressional legislation, helped to make newspapers a flourishing part of life in the United States. The act settled two debates about newspapers and the mail.

First, it ensured that every newspaper would be admitted into the mail system, so the government would not be the arbiter of which newspapers were distributed by mail.

Second, there was a vigorous argument over whether newspapers should be carried for free, or pay a reduced rate. Southerners worried that the larger Northern newspapers (many of them anti-slavery) would overwhelm the South if they were distributed for free, so the “reduced” postal rate prevailed.

Since then, newspapers have been distributed through the mail at reduced rates as a public service, a covenant that was again made explicit in the Postal Policy Act of 1958. In 1960, second-class postage charges covered only 23% of the cost of mailing.

But the covenant began to unravel after the reorganization of the postal service in 1970. Rates increased, and by the 1980s, second-class charges covered more than 100% of the postal service’s costs of mailing. In other words, the USPS was making a profit on delivering periodicals. In the 2000s, periodical rates dipped below 100% of costs again, but the premise that periodicals bear the full USPS handling costs and overhead still remains.

We are now at a critical moment for the nation’s newspapers. A useful policy proposal for today is to recover a great idea from 1792 – that newspapers should be freely distributed by the U.S. Postal Service.

Yes, eventually, digital distribution will be the norm, but it may be many years away for most newspapers. As news industry analyst Ken Doctor has noted, pushing newspapers to digital too soon would be like “burning a bridge they still need to cross.”

Large national papers like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal are finding sustainable models with digital subscriptions. For large regional and metro papers, “digital-only delivery may offer a lifeline,” says Penelope Muse Abernathy, the University of Northern Carolina researcher, but only if they can convert tens of thousands of print subscribers. That represents a dramatic drop in revenue for many publishers, when the digital subscription price point averages 23% of the print subscription price. For the nation’s thousands of dailies and weeklies, with small market sizes and only a few thousand subscribers overall, Abernathy argues that digital subscriptions and advertising generate relatively insignificant revenue.

Fully subsidizing print distribution covers a substantial fixed expense and can help sustain most of the nation’s 6,730 newspapers for what may be a very long transition period.

But, this must be done with more support for the USPS, which is also at a critical moment in its history. The USPS is chronically underfunded, and its collapse would threaten free elections and a major distribution system for newspapers. Sufficient financing for the post office and full support for newspaper distribution by mail would benefit two of the nation’s most fundamental civic institutions.

What difference would free mail distribution make for small-town newspapers, where postage is the third largest expense, after payroll and newsprint?

Matt Bryant, publisher of the Southeast Iowa Union, said “it would definitely help” and that postage makes up about 4% of his total expenses.

At the Iowa Falls Times-Citizen, Tony Baranowski, director of local media, said “no postage would definitely be a relief for us … It would change the shape of our budget.”

And, at The Storm Lake Times, “It would be a huge help to us,” Cullen said.

How much would it cost to completely subsidize newspapers distributed through the mail? In fiscal year 2020, the USPS generated $73.2 billion in revenue, although it still is awash in red ink from annual shortfalls and billions in unfunded liabilities. Revenue from newspapers and magazines combined in FY2020 was $1 billion; covering that cost would amount to about 0.02% of the federal budget.

There is no single answer to save newspapers, but we cannot afford to lose more of them. Fully subsidizing second-class mail delivery of newspapers is a public service that our democracy desperately needs now.

Christopher R. Martin is a professor of digital journalism at the University of Northern Iowa and a Center for Journalism and Liberty Contributing Scholar.